An excerpt from Joyce Carol Oates’s Nighthawk: A Memoir of Lost Time

I arrived by air, breathless with anticipation. I arrived alone. I see myself across an abyss now of four decades as a figure of uncertainty like a line drawing by Saul Steinberg.

In years I was an adult of twenty-two, in experience I was still an adolescent. I was romantic-minded and vulnerable to hurt as if the outermost layer of my skin had been peeled away. I was the quintessential daughter-student in whose male elders’ eyes I was judged “bright” – “brilliant” – “an outstanding student”- a “promising writer.” … I’d been valedictorian of my graduating class at Syracuse University, and I’d been named a Knapp Fellow at the University of Wisconsin, where I intended to enroll as a PhD candidate in English. By romantic-minded I mean romantic in terms of books, literature, a practical career of university teaching. My vague, unexamined belief was that my “own” writing, fiction and poetry, would somehow fit into this scheme.

This great adventure! I’d fled the East because I had no wish to marry, and yet, within five swift months, in Madison I would fall in love, and marry; within ten months I would have become profoundly disillusioned with the PhD-scholarly-academic profession, even as I earned the master’s degree qualifying me to teach English as it happened I would do, in universities (currently Princeton) for more than four decades; I would, in Madison, cease writing anything except the most conventional or scholarly-critical papers, a development that would have seemed to me until this perilous time tantamount to ceasing to dream, or to breathe.

(Was there was no hope of adroitly mixing the academic and the “imaginative” at Madison, as I’d done at Syracuse? There was none. My graduate-level professors, most of them Harvard educated, were a generation older – or more – than my Syracuse professors and resisted even the analytical New Critical approach to literature; to these conservative elders, with the notable exception of the medievalist Helen C. White, canonical texts were to be approached as sacred-historical documents primarily, to be laden with footnotes as a centipede is fitted out with legs. When, in my initial idealism, I wrote a seminar paper on Edmund Spenser and Franz Kafka, on the ways in which the allegorical and the surreal are akin, my professor, the eminent Merritt Hughes, who knew nothing of Kafka and had no interest in correcting his ignorance, returned the paper to me with an expression of gentlemanly repugnance and suggested that I attempt the Spenser assignment again, from a more “traditional” perspective. My face burned with shame: I was made to feel, in the eyes of the other graduate students as in Professor Hughes’s disdainful vision, a barbarian who stood before them naked, utterly exposed.) …

A disquieting odor as of disinfectant, bandages, and cafeteria food pervades my memory of Barnard Hall, the graduate women’s residence in which I lived for a brief yet exhausting semester, though of course this is absurd and unfair; Barnard Hall wasn’t a hospital, and its occupants, graduate women, so very different in the aggregate from the undergraduate women with whom I’d lived for four years at Syracuse, weren’t patients or convalescents; on the contrary, these women, some young and others less so, exuded an air of determined bustle, grim-cheery energy, like novice nuns in a convent who must brave the world outside the convent, run by men, the other. (In fact, there were two nuns on my floor, from different orders, living in separate rooms.) My convent-room with its single window looking out onto University Avenue was on the third floor of the residence, and in that room in the first week I was stricken by insomnia as if by a swarm of invisible mosquitoes lying in wait in that space. No matter how exhausted I was from hours of reading, writing, library research, the restless walking-running that has long characterized my life, no matter how I tried to calm my rampaging thoughts. Insomnia! …

Madison, Wisconsin, was in those days an idyllic college town built upon the southern bank of Lake Mendota. The enormous campus inhabited woodland near the lake; the terrain was nearly as hilly as Syracuse, a landscape long ago convulsed by glaciers and retaining still, even on sunny autumn days, a wintry-windy flavor to the air. In Madison as in all new places before habitude dulls, or masks, strangeness, I realized how precarious our hold upon what we call sanity is. …

In Madison, during these months of intense academic study, when my head was filled with Old English, medieval and Renaissance and eighteenth-century English literature, of course I wrote no fiction or poetry, nothing of my “own” (as I thought it) except desperate fragments in a journal like feeble cries for help. As my imaginative life was smothered in the service of academic study, my intellectual life was heightened, revered, run to exhaustion like a hunting dog whose only food will be the terrified prey he flushes out for his master. (Hunting dog, prey, what’s the distinction?) I admonished myself, What did you expect, this is graduate school. You’re training to be a scholar. To be a serious adult. This isn’t dreamland. To write about my “lost time” in Madison is very difficult even decades later. To violate the taboo of exposing the self, and those innocent individuals intimate with the self, is simply not possible. But mostly I’ve never written about my Madison sojourn because I have never known how. Emotions are the element in which we live, or fail to live; “events seem to us comparatively detached; yet, in speaking of oneself, emotions are of no more interest than dreams; it’s historic event that seems to matter, and one is baffled at how to match event with emotion, emotion with event. Our most profound experiences elude all speech, even spoken speech. What vocabulary to choose to attempt to evoke a flood of sheer, untrammeled emotion? – the common experiences of grief, terror, panic, falling-in-love, desperation-at-losing-love. For me, the vocabulary of loss, despair, frustration, defeat is inappropriate, or inadequate, in writing of my months in Madison, since in fact, much of the time, and nearly always publicly, I was very happy; after I met the man I would marry, I would have defined myself, and would certainly be defined by others, as very happy. For one can embody without at all understanding the paradox that one can be both happy and desperately unhappy at the same time; contrary to Aristotle’s logic, one can be X and non-X simultaneously. …

Yet my happiest, my most romantic morning-insomniac adventures were out-of-doors. If it wasn’t bitter cold, or raining, or snowing, or oppressively windy, I gave up on Barnard Hall, dressed, and began the day early, in darkness. I’d grown up on a small farm in western New York, and rising early in the dark, in terrible weather, had been routine. Through the winter, the school bus swung by our road at about 7:30 a.m., in darkness. By my logic, to begin a day before 4:30 a.m. was eccentric; after that hour, when the clock’s hands were moving toward 5:00 a.m., beginning a day was normal, a sign of optimism. Who knew what adventures the new day might bring? Outside the claustral residence hall I felt a surge of energy, for energy is hope, and hope is energy, and I would break into a run, as if I had an immediate destination; I ran on University Avenue and on Park Street to the foot of Bascomb [sic] Hill, and up the steep, windy hill itself until I could run no longer. (Hours later, midmorning, I would be among forty or so graduate students seated in a classroom in Bascomb Hall, in a hallucinatory drowse trying to take notes as the eminent Renaissance scholar Mark Eccles lectured on the Elizabethan-Jacobean drama, reading from copious notes in a quiet, uninflected voice like a hypnotist’s.) In the gradually lightening dark I would continue past Bascomb Hill, in the direction of the observatory; my ultimate destination was a State Street diner that opened early, but I forestalled going there too soon; in these long-ago years a dense stand of trees, deciduous and evergreen, bordered the hill; beyond was Lake Mendota; I would return, down the long hill, passing by the State Historical Library and the mammoth Memorial Union, not open at this hour; if it wasn’t too cold or windy, I’d walk along the lakefront; I’d pause on the terrace, to stare at the lake; here, I was nearly always happy; freed from the confines of my room and from the rampage of my thoughts; I was exhilarated and yet comforted by the lapping waves, and Lake Mendota was often a rough, churning lake; in the twilit early morning it appeared vast as an inland sea, its farther shore too distant to be seen. On misty or foggy mornings, which were common in Madison, the lake’s waves emerged out of an opacity of gunmetal gray like a scrim; there was no horizon, and there was no sky, and it would not have surprised me if when I glanced down at my feet I saw that there was no ground. …

Often in my circuitous route to the State Street diner, I would pass the still-darkened university library, which was one of my places of refuge during the day; swiftly I’d walk along Langdon Street, past fraternity houses, impressive façades bearing cryptic Greek symbols emerging out of the gloom, and invariably there were lights burning in these massive houses, who knew why? I was quick to note isolated lights in the windows of apartment buildings and wood-frame rental houses on Langdon, Gorham, Henry, as the early morning shifted toward 6:00 a.m.; still darkness, for this was autumn in a northerly climate, but with a promise of dawn in the eastern sky. The nighthawk takes comfort in noting others, kindred souls, but at a distance: warmly lit city buses on Gorham and University bearing a few passengers; headlights of vehicles; occasional pedestrians; a few among these might have been morning-insomniacs like me, relieved and grateful for the new day, the new chance, but most of them were workers, custodians, cafeteria staff, attendants at the university hospital; for them there was no special romance to the hour, nor probably any malaise; beneath their coats they wore uniforms. …

In January 1961 I was married, and moved from Barnard Hall to live with my husband in a surprisingly spacious, airy five-room apartment on the second floor of a wood-frame house on University Avenue, a mile away from the university residence in which I’d spent so many insomniac hours. In May, one sunny morning, I was examined for my master’s degree, in venerable Bascomb Hall for what would be the final time. My examiners were all men; two were older professors with whom I’d studied and who had seemed to approve of my work; the third was a younger professor of American literature, very likely an assistant professor, who stared at me, now “Joyce Carol Smith,” doubtfully. A married woman? A serious scholar? It did seem suspicious. In this man’s unsmiling eyes, I saw my fate.

Two-thirds of the exam went well: I’d followed my husband’s advice and memorized sonnets by Shakespeare and Donne that I could analyze and discuss; I could recite the opening of Paradise Lost, and key passages of “Lycidas” and “The Rape of the Lock”; but the youngish professor of American literature was unimpressed, biding his time. He didn’t question me about primary works at all. I might have spoken knowledgeably about the poetry of Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman, but I wasn’t given the opportunity; as in a courtroom nightmare, I was asked only questions I couldn’t answer with any confidence about dates of poems, publications, editions; for instance, how did the 1867 Leaves of Grass differ from the 1855 edition, and what were the circumstances of the 1871 edition? Through a haze of shame I heard myself murmur repeatedly, “I don’t know,” and, “I’m afraid I don’t know.” …

How vulnerable I’d been, that May morning in 1961! How negligible in his eyes, how expendable, a young woman, and married; not a likely candidate for the holy orders of the PhD. And it was so: though my love for literature was undiminished, I’d become profoundly disillusioned with graduate study and couldn’t have imagined continuing in Madison for another year, let alone two or three; my subterranean despair would have choked me, and destroyed the happiness of my marriage; it would have destroyed my marriage. The drudgery of scholarly research and the mind-numbing routines of academic English study, above all the anxious need to please, never to displease, one’s sensitive elders, weren’t for me. My major writing effort of the year was a one-hundred-page seminar paper on Herman Melville tailored to the expectations of a quirky, very senior professor named Harry Hayden Clark, who had a penchant for massive footnotes and “sources”; this document was well received by Professor Clark but so depressed me that I threw away my only copy soon afterward.

The verdict of the examining committee was that “Joyce Carol Smith” be granted a master’s degree in English from the University of Wisconsin; but she was not recommended to continue PhD studies there. The verdict was You are not one of us, and how could I reasonably disagree?

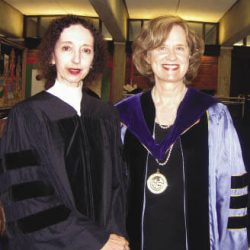

When, a quarter-century later, in what might be called the second act of a fairy tale of wavering intentions, I returned to the University of Wisconsin at Madison to be given an “honorary doctorate of humane letters” in an elaborate commencement ceremony, the occasion would seem surreal to me; I couldn’t help brooding on the irony of the situation, and perhaps the perversity, hearing my name amid those of other “distinguished alumni”; not that I was an impostor exactly, but if I hadn’t been rejected as a PhD candidate in 1961, if, instead, my examiners had urged me to continue with graduate work, I might have succumbed to the temptation; if I’d been a young man, for instance, of equal talent, I might have made myself into another person, and I certainly wouldn’t have been invited back to Wisconsin to be graciously honored. The paradox was not one that might be elevated to a principle for others: to be accepted by my elders in one decade, I’d been required to be repudiated by my elders in an earlier decade.

And now, at an even later date, 27 September 1999, as I compose this memoir in a room at the Edgewater Inn in Madison, Wisconsin, overlooking a rain-lashed Lake Mendota, I’m forced to recall the bittersweet irony of my situation; another time I’ve been invited back to Madison, to give a public reading in a beautiful art museum built long after my departure, and to be honored at an elaborate dinner with the chancellor, his wife, and a gathering of the university community. Honored at the age of sixty-one as an indirect (and yet irrefutable) consequence of having failed at the age of twenty-two! …

In Madison, I’ve been made to feel at last that I do belong. I’ve arrived at an age when, if someone welcomes you, you don’t question the motives. You don’t question your own motives. Rejoice, and give thanks!

Of our hurts we make monuments of survival. If we survive.

This has been a fragmentary memoir of a lost time; a time for which there was no adequate language; and so the effort turns upon itself like a Mobius strip, shrinking from its primary subject. I am paralyzed by the taboo of violating the privacy of individuals close to me, and by the taboo, which seems a lesser one, of violating the privacy of one’s own heart; exposing the very heart, vulnerable and pulsing with life. There are intimacies, secrets, epiphanies and revelations and matters of simple historic fact of which I will never speak, still less write. Yet I’m thinking, in Madison, Wisconsin, in the early morning hours of 28 September 1999, of that Sunday afternoon, 23 October 1960. I’d come to the reception in the Memorial Union overlooking this same lake, these waves, about a mile from where I’m sitting now, composing these words. I’d come to the reception by myself. I knew no one. I was one of three thousand graduate students at the university, and perhaps fifty or sixty had come to this lounge in the student union; I was sitting at a table with some others, their faces now long forgotten, and in the corner of my eye I saw a figure approaching. I have no memory of myself except that I was dreamy-eyed, listening to the conversation at the table without joining in; I wouldn’t glance around with a bright, hopeful, welcoming American-girl smile at whoever was coming near. In one of my own works of fiction such a figure, undefined and mysterious, might turn out to be Death – but this wasn’t fiction, this was my life.

Still, I didn’t glance around. Until, when a man asked if he might join us, and pulled out a chair to sit beside me, I did.

Published in the Summer 2009 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.