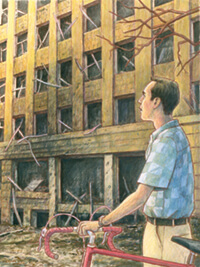

After the Bombing

As with many eventful days, Monday, August 24, 1970, began in perfect normalcy. I was an organic chemistry graduate student at the University of Wisconsin, where my research laboratory was in the chemistry building. That morning, I approached the building on my bicycle to find broken glass everywhere. More than one thousand windows in twenty-six campus buildings had been shattered. One was mine.

At 3:42 a.m., four Vietnam War protesters, calling themselves the New Year’s Gang, had detonated a stolen van containing two thousand pounds of ammonium nitrate-fuel oil mixture after parking it outside Sterling Hall, the physics building. Their target was the Army Mathematics Research Center, which was housed inside the building. A series of articles in the Daily Cardinal had claimed that research conducted there was aiding U.S. military efforts in Vietnam.

The New Year’s Gang had taken its name after a failed attempt to bomb the nearby Badger Ammunition Plant the preceding New Year’s Day by dropping mayonnaise jars filled with explosives from an airplane. The bomb used on Sterling Hall was concocted near Devil’s Lake State Park, where, ironically, my girlfriend, Fran Haemer ’70, and I had camped that weekend. The blast caused more than $2 million in damage. It killed physics postdoc Robert Fassnacht, the father of three children, and wounded three others.

The window by my laboratory desk faced the Army Math Center, about a block away across University Avenue. The glass and window shade were blown in. A small shelf on my windowsill, where I stored my painstakingly synthesized research compounds, was knocked over. I was grateful that I hadn’t been sitting in my chair; it was covered with chemicals and shards of glass. A bottle containing deuterium-labeled sulfuric acid, which I had prepared to do tracer studies on my compounds, lay broken on my desk. Labeled or not, sulfuric acid is sulfuric acid, and it had charred the large sheets of paper that held my valuable nuclear magnetic resonance images. It took me about a month to replicate my data. By comparison, the impact on my research was minimal. Some physics students lost a year of work.

Everyone had strong opinions about the war. The killing that spring of four students by the Ohio National Guard at staid Kent State University, near where I had grown up, upset me profoundly. But as a rule, chemistry students didn’t participate in demonstrations; we were too involved in our research. Still, fellow graduate student Ron Markezich PhD’70 and I did manage to get tear-gassed once when we decided to watch one of the almost daily encounters between the police and the protestors, and we got caught in the crossfire. Once was enough.

I was also serving in an Army Reserve intelligence unit at the time. As weekend warriors, our view of the protests was pretty casual. We met at the Army National Guard and Reserve Center on South Park Street, and considered our major responsibility to be the defense of the Kohl’s supermarket parking lot next door, should the Russians invade on a Saturday. Our usual campus attire was our military-issued field jackets. Apparently, some reservists were spotted at a protest and were reported to their unit, prompting our first sergeant to tell us, “[If] you’re going to wear your jackets to a riot, at least take off your name tags.”

“Make love, not war” summed up our sentiments nicely.

Shortly after the bombing, I began a three-month push to finish my thesis. I graduated that January and left Madison for a job in Europe. Three of the bombers (Karleton Armstrong; his brother, the late Dwight Armstrong; and David Fine) were eventually caught and served modest sentences. The fourth, Leo Burt, disappeared, and his fate remains a mystery.

Madison was vibrant in the late sixties. The stuff of daily life was flavored with parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme … and perhaps a touch of indecency. The Army Math bombing precipitated the end not only of the campus peace protests, but also of an era. The cohort of 1970s free-spirited baby boomers left and went on to become yuppies. If Madison was indeed the Athens of the Midwest, as we claimed at the time, the bombing brought down not only one of its buildings, but its Periclean Age.

Heinz Stucki retired after many years in the chemicals and polymers industry, but still teaches courses in general and organic chemistry on a part-time basis. He lives on forty-three Appalachian acres near Newcomerstown, Ohio.

If you’re a UW-Madison alumna or alumnus and you’d like the editors to consider an essay of this length for publication in On Wisconsin, please send it to onwisconsin@uwalumni.com.

Published in the Fall 2010 issue

Comments

jim wiedmeyer March 20, 2011

looking for artical on 10 or 20 year anniversary of sterling hall was a member of unit on large picture of v going into crowd

had copy but lost

jim wiedmeyer

5341hy60

slinger wi 53086 retired member 127 inf hartford wi

Nancy Oakes Briggs BSN 1969 April 15, 2012

Whenever I read about the bombing at the Army Math Research Center building, I remember my own experience from that night. I am an RN and was working on the 3rd floor of the old UW hospital (the Obstetrics/Nursery unit) on University Ave.

I was in the nursery at the time of the bombing and facing south (University Ave). I was putting an infant into an isolette (incubator) at the time of the blast and remember vividly the sky turning orange, a tremendous noise, and the building rocking from the bomb impact.

I vividly recall considering evacuation of all patients/babies and staff,and getting the oxygen supplies shut down. I did a quick inventory-no women were in labor at the time, and we could evacuate quickly-each mother could take their own baby and the staff could get the rest of the babies out.

Not knowing what was going on was intense-gradually we learned what had happened and there was no need to evacuate.

Before morning, I went to the east side of the hospital-all the windows were blown out. I remember hearing that a few patients had minor cuts from the glass but no serious injuries.

The experience was “mind blowing”. I walked around the hospital in the AM when I finished work. I remember lots of men in suits and thinking-they must be FBI agents. I heard lter that the blast could be heard/felt for miles.

The experience was frightening-considering the proximity of the hospital with so many people in it. It is with sadness I remember learning about the tragic death that also took place.

I think of this everytime I go past the old Hospital on University Ave and hope that non-violent dialogue will prevail.