Letters: The Sterling Hall Bombing

Alumni respond to our 50th-anniversary article “The Blast That Changed Everything.”

The 1970 bombing of UW–Madison’s Sterling Hall has been extensively covered in histories of the Vietnam War protest movement, but On Wisconsin’s 50th anniversary piece in the summer 2020 issue was a unique contribution to the historical record. “The Blast That Changed Everything” sought out eyewitness testimony from dozens of alumni who had never publicly commented, shedding new light on the campus environment before and after the bombing. It mirrored people’s experience of the tragedy, progressing from the chaos of the moment to reflections on the consequences.

We received an outpouring of responses to “The Blast That Changed Everything,” ranging from vivid memories of the bombing to personal perspectives. On the 51st anniversary of the August 24 event, we offer a selection of letters, edited for publication.

***

I knew and worked with Bob and Stephanie Fassnacht. Before I left in 1969, my offices were 100 yards from where Bob was killed. Your photo on page 33 brings back the smell of tear gas wafting over from the Commerce Building in 1967.

As if it were yesterday, I remember where I was when I heard the news. Another UW physics grad met me on the way to the cafeteria of the Brookhaven (New York) Lab. “They blew up the physics building last night,” he said.

In 2005 my wife and I attended the dedication of the new physics department. I took her to the plaque, as I did our daughter (BS’04) in 2012. It is appalling that some of the students whose memories you quote think that this event had any effect whatsoever on saving lives by shortening the Vietnam War or influencing any decision by President Nixon. (I was probably the only Nixon supporter among my fellows, but back then we didn’t let politics poison our friendships.)

Stephanie may have chosen not to bear a grudge, but I cannot forgive, especially those whose words and deeds led to this evil act. A good man killed and a great physics department devastated.

James W. Waters PhD’69

I was a grad student at the UW when Sterling Hall was bombed. Forty years later, I was approached by two FBI agents while working on my farm on Virginia’s Eastern Shore. They said that a woman watching America’s Most Wanted had reported seeing the featured fugitive in the area and asked me if I had seen anyone strange. I was shown an FBI wanted flier with two photos, one of Leo Burt as he looked at the time of the bombing and a computerized update of how he might have looked decades later. It showed him with a graying beard (like mine). I was asked if I recognized him. I did not and asked what he was wanted for. Told, I was amazed at the apparent coincidence and immediately said that I was there at the time. The agents found that interesting, but left.

Twenty minutes later I saw one walking through my tick-infested hayfield in his gray suit, where I was loading hay from the barn. He asked for my fingerprints and said they had to be taken at the local sheriff’s department. Having a lot to do, I reluctantly consented. Driving me there with the other agent and a local deputy, he told me that he was positive I was the bomber.

There, he showed the updated photo of Burt to all the deputies and the sheriff; they all agreed that it was me. I was beginning to be a bit concerned; although it was unlikely any prints they had would match, I did not completely trust the motives of the young agent who might have seen this as an opportunity to impress his superiors about his prowess.

Long story short, the prints did not match and I was free to go. Lesson learned? Beware of eyewitness testimonies!

Matt Cormons MS’71

Much can be understood by what the article mentions, and much can be learned from what the article does not mention.

A good job of understanding the bombing on an individual level is clearly achieved. Many thoughtful statements are combined on a variety of issues. However, there is no mention of years of police attacks and violence, facilitated by the University of Wisconsin, on those who opposed the war in Vietnam. Although the article focuses a great deal upon the tragic death of Robert Fassnacht, nowhere are the names of Wisconsin young men who killed and/or died in Vietnam mentioned. Needless to say, the millions of Vietnamese dead remain completely unmentioned.

I learned many things during my undergraduate education at the University of Wisconsin and my residence in Madison. Some of those things I learned in the classroom as a political science major. The principal lesson that I took away from my years at the University of Wisconsin, however, came from outside the classroom. No matter how much time is spent talking about freedom and dissent in this society, if one dissents upon a truly meaningful issue with many others, the forces of state violence and state repression will be brought to bear in an attempt to create silence through death, injury, and intimidation.

There is another generation learning this lesson as I write. May they never accept silence and may they ever work for change.

Charles W. Hunt ’68

I was in my last year of my PhD in organic chemistry, and we had labs on the sixth floor of the new chemistry building. Whenever the National Guard was called out, they took over our TA room in the basement.

My fiancée and I were asleep in an apartment about eight blocks away, and when we heard the explosion, the question was, “Who got it?” It was obvious that it was a bomb, and we initially thought it was one of the ROTC buildings. When we walked to school, we could see the damage, and also physics grad students trying to find parts of their lab notebooks.

That day, I took my duplicate copy of my lab notebook home, along with some of the chemical compounds that had taken me so long to make, until I could run more experiments. Rumors had it that our building was a target since we had a theoretical chemistry group on the eighth floor, run by a prof who had worked at Los Alamos on the bomb during World War II.

It was a sad day, and the country was as polarized then as it is today.

Stephen Ziman PhD’69

I much appreciate all the work you put into that article. I was most surprised that any alumni would ever write about admiring “the courage of the Armstrongs and David Fine” or say the researcher’s death was just “one of many.” That is just upsetting.

Michael W. Rathsack ’69

Your 50-year perspective on the bombing of Sterling Hall brought back vivid memories and emotions. My husband and I had just returned from our honeymoon to set up our apartment prior to starting our senior and junior years. Our mood was changed forever as we went to the incredibly awful scene at Sterling and Old Chem with large gaping holes and parts totally gone. The huge banner above the Sterling front entrance brought it into perspective: “The Faculty of the UW Physics Department Does Not Condone Violence as a Means of Protest.” Words that remain with me still.

Roberta (Collins Jacques) Harper ’72

I was spending the night at a friend’s apartment on Randall Avenue and having trouble sleeping. Lying in bed awake, I felt more than heard a vast explosion and literally looked at the walls to see if they were going to collapse in on me. They didn’t, and I jumped out of bed, got dressed, and ran outside. Everywhere I looked there was broken glass, and my first thought was that if the police came along, they would think I had broken all the windows, so I ran back inside.

After a moment I realized that was ridiculous. The police would have heard the explosion, too. A couple ambulances tore by, and I headed in that direction. I got to Sterling Hall less than 15 minutes after the blast and was forever struck with several details. First the gaping and still-smoking hole in the side of the building. Second, Chancellor Young walking around wearing a sweater with leather patches on the elbows. Third, the ground was ankle-deep in leaves blown off all the trees, mixed with slivers of metal.

I’ll never forget that night.

Ken Bingenheimer ’72

Robert Fassnacht was not the only physicist whose life was cut short by the blast. Professor Joseph Dillinger, Fassnacht’s adviser, died in 1975 at the age of 59, and I believe the results of the blast led to his premature death. Professor Dillinger was a kind and gentle man who was easily one of my best teachers of physics. I took his thermodynamics course during the academic year after the bombing. He talked about it often during class and was clearly tormented by it. There is no doubt in my mind that his mental anguish affected his health.

Dennis Goldstein ’72, MS’74

“The Blast that Changed Everything” makes note of the fact that Robert Fassnacht “could both play a harpsichord and handle an M1 rifle.” He not only played the harpsichord; he built one!

That harpsichord now graces the sanctuary at Westminster Presbyterian Church in Madison. In light of the 50th anniversary of Fassnacht’s death, I have asked the pastor and the music director to commemorate the history of the instrument by installing a plaque that honors his memory.

Robert Fassnacht remains with us in the lives of his children and in the music from his harpsichord.

Carol S. Wright

Thank you for “The Blast that Changed Everything.” Reading the article instantly transported me to that August 1970 day.

Two other graduate students and I had put the finishing touches on our little apartment. I had just put up my bookshelf, made of bricks and boards, before turning in for the evening. My bookshelf was not yet securely attached to the wall. When we heard the loud boom that woke us up, I thought my bookshelf had fallen. My roommates came to my room and we were all surprised that the shelves were still standing. We looked out a window and saw people in pajamas and quickly thrown-on clothes in the streets running toward campus. We quickly dressed and ran out to join them. We had no idea what was happening. Suddenly we heard shouts of “it was a bomb” that turned into shouts of “there may be a second bomb.” That scattered everyone; people were running toward campus while others took cover.

Later my adviser told his graduate students to keep our research and collected data with us instead of leaving it in the building (I was a psychology grad student).

The name Robert Fassnacht was indelibly etched in our brains. To this day I still remember it.

Cynthia L. Morgan PhD’74

I just read your article about the Sterling Hall bombing, an excellent account, so my compliments. I was in the Army Math Research Center area visiting a professor that afternoon about 12 hours before the explosion.

While on campus, I happened to be attending an international meeting on graph theory sponsored by the Army Math Research Center when a group of students burst in and threw balloons full of red paint at the audience. I got covered and can remember thinking, “I’m glad these aren’t machine gun bullets!”

Those certainly were memorable times.

Brian White MS’71, PhD’73

In spring 1971, I completed my senior year at the UW doing directed research in Middle Eastern history while residing in Jerusalem. As a student in Madison, I was very involved with academics and motorcycles, but not in the antiwar protests. However, in my sophomore year (1968-69), I lived next door to Ken Mate (above Ella’s Delicatessen), who was then one of the purported leaders of Students for a Democratic Society on campus. I did not know any of the Sterling Hill bombers nor was I in the U.S. when the bombing took place.

Early one morning in April 1971, there was a loud knock on the door of my Jerusalem apartment. When I opened the door, I was confronted by two FBI agents accompanied by an Israeli security agent. Apparently the FBI had leads that bomber David Fine had fled to Israel where he was supposedly in hiding. Based on this lead the FBI sent two investigators to Israel, and I was being interviewed as a “known associate” of Kenny Mate. I was amazed that they had a dossier on me simply because I was a neighbor of Kenny — they seemed to know everything about my life in Madison. That being said, they should have known I was not involved in any campus politics.

The interview only lasted for a few minutes since I had no information to impart, but the experience shook me up and left a lasting impression.

Robert Damast ’71

I am a United States Navy Vietnam combat veteran who read “The Blast That Change Everything” with great interest. Prior to that reading, I was under the impression that the vast majority of Americans had come to believe that never again would Americans blame other Americans for carrying out government policies and then be ill-treated; and that only those Americans who made the policy would be so blamed. Apparently some of our fellow alums have sickeningly rejected that thesis.

The most disgusting statement I read in the article was the attempt to justify the killing of Robert Fassnacht as “I’ve always viewed his death as part of the death toll of the Vietnam War.” That is rationalization taken to the nth degree.

Jerry Alperstein ’64

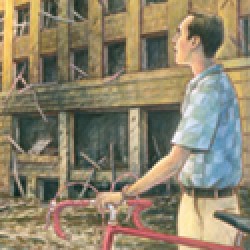

I got my PhD from Wisconsin in ’69. My lab, in which I had spent five years, was just behind the full first-floor window on the right in Sterling Hall in the picture shown on page 30. Although I had left 18 months earlier, tears still come to my eyes when I read your article.

George Beitel PhD’69

Published in the Fall 2021 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.