The Meandering Path to a Nobel Prize

With a little luck, William Campbell MS’54, PhD’57 discovered a drug that has helped millions see.

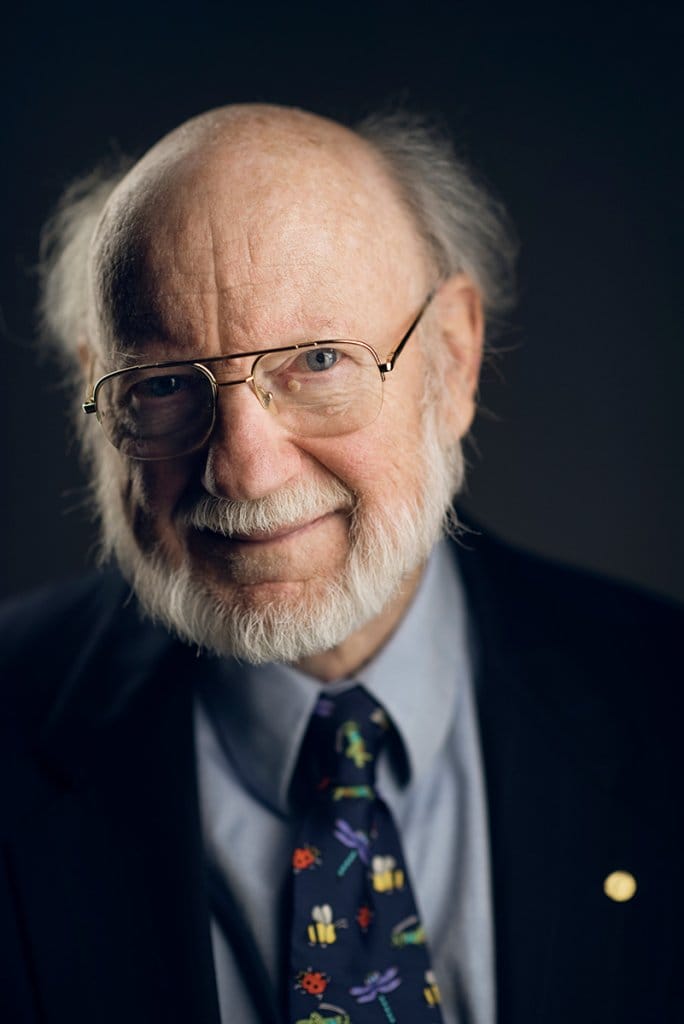

Campbell developed the drug ivermectin to fight heartworm. It also prevented river blindness, saving millions of people from losing their eyesight. Alexander Mahmoud

William Campbell MS’54, PhD’57 never meant to come to Wisconsin. In fact, much of his life seemed unintended — he hadn’t really meant to study parasites, to work in tropical illness, to seek cures for people’s ailments. But by luck and happenstance, he did all those things — and ended up discovering the drug ivermectin and winning a Nobel Prize.

“It happened by chance,” he says, “and throughout my life, I’ve been impressed as to the role of chance in the big moves in our lives.”

Campbell grew up in Ireland, and as a high school student, he went to an agricultural show and tucked a brochure on animal illnesses in his pocket. Years later, while at Trinity College in Dublin, he was thinking that maybe he should study medicine when a teacher made him think of that brochure again.

“The professor, Desmond Smith, was a parasite guy,” Campbell says. “It immediately crystallized or focused my interest. I often think how lucky a student can be when you encounter a professor who changes your life. I had originally come to study medicine, but because of him, at the last minute, I changed my mind and switched to natural science and studied parasitology and never stopped.”

Chance intervened again after Campbell finished his bachelor’s degree. A parasitologist at the UW was looking for likely graduate students. Campbell, not sure what else to do, crossed the Atlantic. He earned his master’s and doctorate, and he went to work in drug development for the pharmaceutical firm Merck. The work was always interesting but seldom fruitful. “In that business, you discover drugs all the time,” he says. “You realize that the chances are that it’s going to be exciting today, but it’s going to totally fall apart tomorrow. It’s going to be useless. It’s going to be unstable or toxic or stinky or whatever.”

But not all of his discoveries fell apart. When he and his fellow scientists were looking for a treatment for heartworm in cattle, they developed a drug called ivermectin. It not only proved effective, but later it found an even more exciting use: it could attack the parasites that cause onchocerciasis — river blindness — in humans.

Before the 1980s, some 40 million people were infected with onchocerciasis; as many as 600,000 of them ended up blind. Ivermectin destroyed the filarial worm that caused the disease. With Campbell’s urging, Merck donated the drug to developing countries. About 25 million people are now treated with it each year. The drug proved so successful that in 2015, Campbell and Satoshi Ōmura shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering it.

“Teamwork was the thing,” Campbell says. “Nowadays it is common for science to advance through teamwork. When it happens, each one is indebted to all the others.”

Published in the Summer 2025 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.