Running from Race

Librarian Louise Butler Walker ’35 took desperate measures to survive in a racist society.

Louise Butler Walker as a young Chicagoan: while she was growing up and as a UW student, she identified as Black. Later in her career, facing the limitations Black Americans experienced, she began to pass as white. Courtesy of the authors

During the Great Depression, Louise Butler Walker ’35 completed her bachelor’s in French and earned a library diploma from what is now UW–Madison’s Information School. Walker had been an outstanding student, graduating Phi Beta Kappa, and completed a prestigious internship at the American Library Association (ALA) headquarters in Chicago. The school’s career placement office said her assets were her “brilliant mind” and “excellent academic background.” Her limitations, they said, were “racial (she is a mulatto).”

Although Walker was not privy to the egregious behind-the-scenes machinations and handwringing about her being Black, she knew that her race was detrimental to her career, so she eventually passed as white to work as a librarian in rural Wisconsin. Her story reveals the extraordinary pressures that African Americans faced.

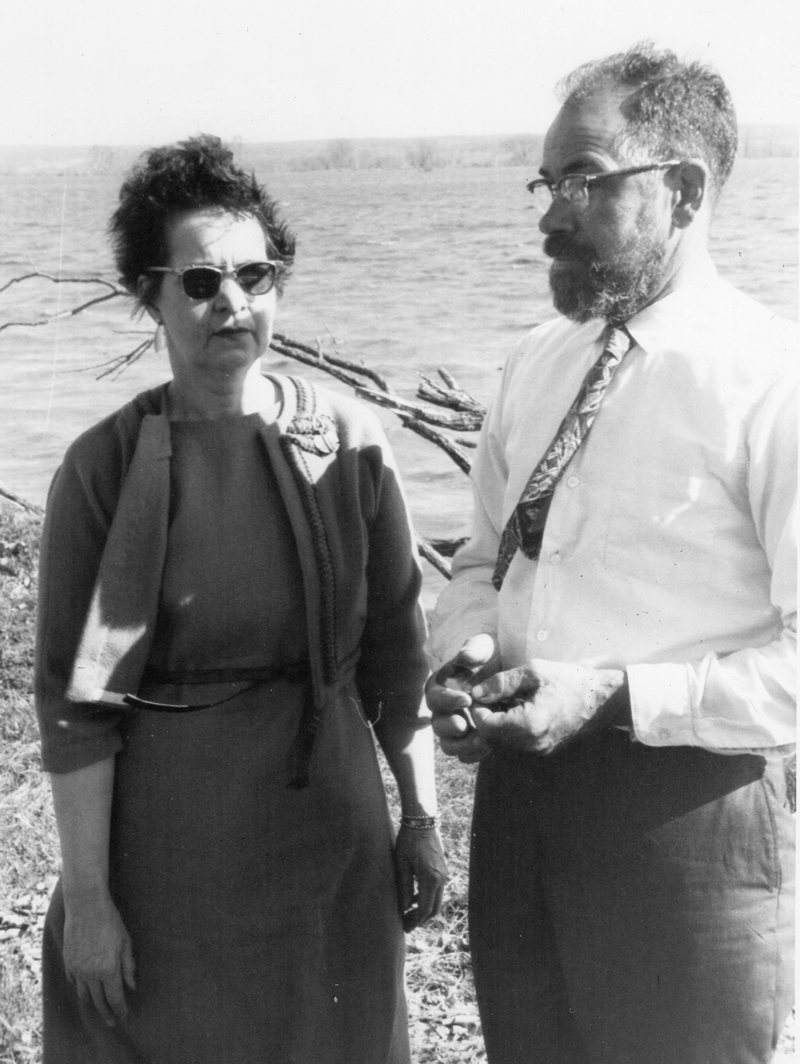

As a local librarian, Walker (at right in photo) became a prominent figure in Fort Atkinson. Courtesy of the authors

Walker was born in Savannah, Georgia, in 1914, to Elizabeth Beasley Thompson, a respected clubwoman and educator, and James Henry Butler, an Atlanta University graduate and editor of the Savannah Tribune, the city’s oldest Black newspaper. Walker’s paternal grandfather, J. H. C. Butler, served for nearly 50 years as principal of the local West Broad Street School and was known as “Prof. Butler” in the Black press. Education was important to the Butlers, and they made sure young Louise received the best education possible. In 1928, she graduated as valedictorian from Cuyler Junior High School, at the time considered “one of the finest Negro grammar schools in the south.” Shortly after her graduation, the Butler family migrated to Chicago, joining thousands of African Americans who moved from the Deep South to Midwestern cities. She matriculated at Hyde Park High School, where she graduated in 1931 with honors — 10th in a class of 360 — and arrived at the University of Wisconsin that fall.

Although previous Black students had been forced off campus into substandard housing, Walker managed to get a room in Chadbourne Hall. The dean of women congratulated herself on this arrangement, noting that Walker had been accepted by all, including Southern students who usually objected to the presence of Black women.

Walker was a member of both the French and Spanish clubs. In the spring of 1932, she was one of 190 women inducted into the local freshman honorary sorority, Sigma Epsilon Sigma.

Walker would continue to challenge rigid expectations prescribed because of her race and gender. During the spring 1934 semester, she married University of Chicago graduate Cyrus Weber Walker, whose race was described on his birth certificate as “multiple.” On the 1910 census, he was listed as “mulatto,” and in 1930 as “Negro (Black).” She soon applied to the Wisconsin Library School, and she was accepted in fall 1935, when Mary Emogene Hazeltine was the director. The descendant of a grandfather who had a station on the Underground Railroad, Hazeltine considered herself to be liberal and supportive of African Americans.

Walker returned to Chicago to complete the required fieldwork for her diploma. She worked variously at the ALA headquarters, the Woodlawn Branch of the Chicago Public Library, and the Schools Division, where she cataloged books for high school libraries.

During Walker’s fieldwork in 1935, Hazeltine received a letter from Hazel Timmerman, the assistant in charge of the personnel at ALA, accusing Louise of “passing.”

“I noticed Mrs. Walker had filled in on the registration card that she was of the white race,” Timmerman wrote to Hazeltine. She asked, “Will you kindly tell me what you are saying to prospective employers in regard to Mrs. Walker’s race? I know that she is in a very difficult position and I want to help her in every way I can.”

Hazeltine responded in the racist language of pseudoscience. “In the case of Mrs. Walker, we say very frankly that she is mulatto (she may have even a lesser strain than a mulatto but I have used that term rather than saying ‘negro’ because it is milder). The Placement Bureau, instead of saying directly what her race was, says that the party might be interested to investigate her race. But I have learned to save one letter by stating frankly that a candidate is a mulatto, or a Filipino, or a Chinese.”

UW–Madison recently announced the Raimey-Noland campaign, a fundraising effort to support diversity, equity, and inclusion programs. It’s named in honor of the UW’s first female and male African American graduates. Mabel Raimey 1918 and William Noland 1875. The Raimey-Noland campaign is part of the All Ways Forward comprehensive campaign.

The year after Walker received her degree, the American Library Association decided to hold its annual meeting in Richmond, Virginia. Black librarians were allowed to attend but were seated in separate sections and were not invited to any events where meals were served. The event led to protestations, and the ALA decided to never again hold their annual meetings in segregated locations.

Back in Chicago, Walker worked on a Works Progress Administration project, at the Board of Education, and for the supervisor of the Organization of Rural Libraries in Cook County. In 1946, her husband was briefly assigned to work in Nebraska, and for the first time they lived in an area where no one knew them. Did people assume that they were white? Was this the first time that they experienced what it was like to live without personal, housing, or occupational restrictions due to their race? Their Nebraskan experience seemed to create a turning point — an opportunity.

The Walkers briefly returned to Chicago and then moved to an 80-acre dairy farm in Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin, in 1947. There they raised two sons while Louise worked as a children’s librarian at the local Dwight Foster Public Library. She quickly became known throughout the community, often visiting local schools to instruct children in the uses of the public library. In addition to her work, she lectured regularly at local social organizations and PTA meetings. When their eldest son, Cyrus “Mike” Michael Walker, decided to attend college at the University of Chicago, they revealed their racial heritage to him, claiming they never told the citizens of Fort Atkinson that they were white, but allowed people to assume that they were.

“My mother always said that she never passed, that she never said she was white, that she never made any reference to it,” Mike says. “I said, ‘Oh, come on. You obviously lived as white and presented yourself as white.’ And she said, ‘Well, it doesn’t matter what I did. I never did anything wrong. It was how people took it. It was up to them.’ ”

The Walkers in middle age: when they lived in Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin, they never told locals they were white but did not correct assumptions. Courtesy of the authors

For Mike, the revelation left him with a sense of confusion. “I had literally no idea of my own racial background,” he says. “I obviously had some questions. I occasionally met relatives. But a large part of the passing meant that we did not see relatives very often. So, I really grew up in a white community acting as white with these kinds of questions. … I spent a couple of years in Chicago sort of running after every Black person I could find saying, ‘Hey, me too, me too,’ and they would look at my perfectly white skin, blondish hair, and light brown eyes and say, ‘Yeah right, not in this lifetime.’ ”

In 1969, after Mike went to college, Walker and her husband grew discontented with the United States’ role in the Vietnam War and moved to a 167-acre sheep farm near Montreal to begin again. Some thought they were running away, but Cyrus said, “We’re leaving for a very simple moral reason: by continuing our American citizenship, we would be putting our stamp of approval on the immoral acts of our government. Since we can no longer love America, we’re leaving it.” Walker remained in Canada until her death in 2000.

Published in the Spring 2021 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.