Six Words about Race

Michele Norris x’83 has been a national TV, print, and radio journalist, but her biggest contribution may be a project that sprang from a painful aspect of her personal history.

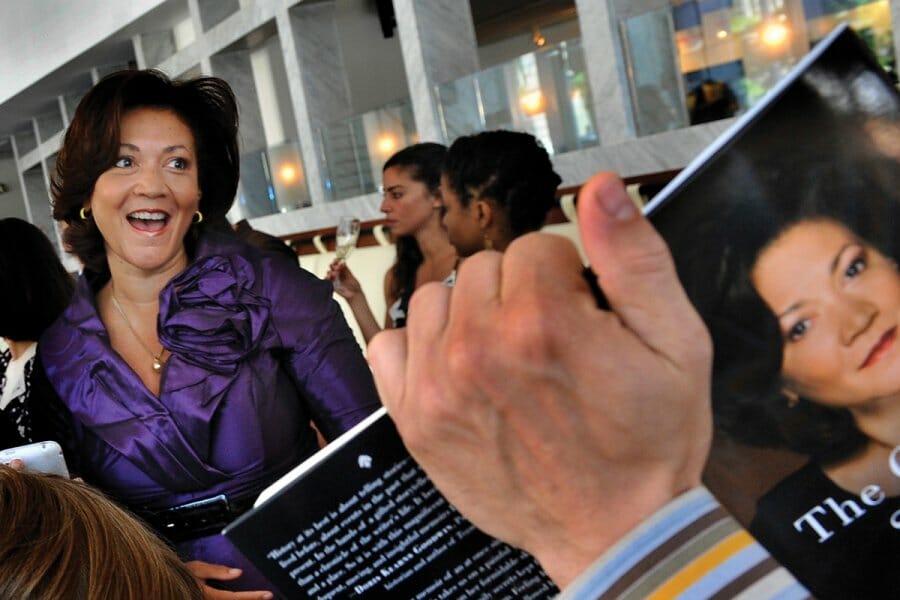

Michele Norris x’83 was worried. A 35-city book tour to promote her 2010 memoir, The Grace of Silence, loomed before her. Norris, then the host of National Public Radio’s All Things Considered, dreaded the thought of standing in bookstores and theaters sharing details of her Minneapolis childhood and adult odyssey of self-discovery. Inevitably, the subject would be race. She presumed most Americans would “rather jump off a cliff” than talk about that with strangers.

But Norris had already taken her own dramatic plunge. “The discussion about race within my own family was not completely honest,” Norris wrote in her book. She had grown up unaware that her family had secrets. It stunned her to learn as an adult that her father, when he was a young World War II veteran, had fled Birmingham, Alabama, in 1946. He had an altercation with a police officer, had been shot, and, fearing dire consequences, left for Minnesota. He never told his children what had happened.

“I was furious. Confused. My head hurt, and I wanted to scream. I needed details,” she wrote. After all, her father was a mild-mannered, book-loving postal worker. He carried a pocket-sized copy of the Constitution in his back pocket wherever he went. A born optimist with a broad grin, he taught her to look for the good in everyone. “Wake up and smell the opportunity,” he told her.

Norris, the winner of an Emmy and a Peabody award, applied her journalistic instincts and investigative shoe leather to learn the details of the event. Her father had been in the wrong place at the wrong time. He tried to stop a policeman from pulling his gun from his holster. When the officer finally did, he pointed the gun at her father’s chest. At the last instant, the gun got knocked away, and the shot grazed her father’s leg.

“Don’t let this make you bitter,” an elderly relative told her.

“Rise. Rise and shine. Rise to the occasion. Rise above it all,” her parents had taught her.

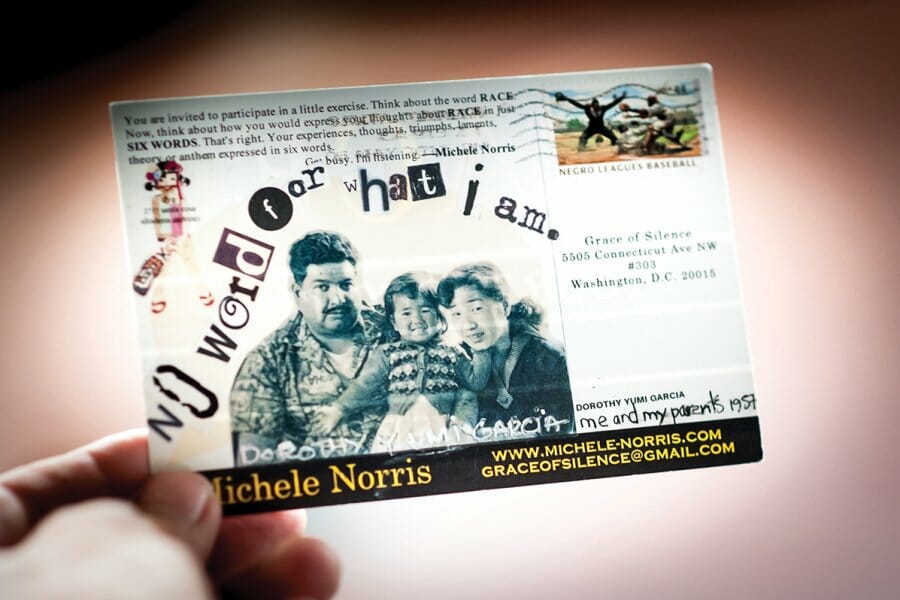

Now Norris rose above her consternation over discussions about race. She had a shining idea — the thunderbolt moment that would change her life. She went to Kinko’s and had postcards printed. Each read “Race. Your thoughts. 6 words. Please send.” She handed them out at events. Thirty percent came back. Soon her publisher, seeing the results, took over the printing. Three years later, she had 150,000 responses.

Today more than 500,000 people from all 50 states and 96 nations have submitted entries (and personal stories) to The Race Card Project, which Norris calls “a trusted space that excavates hidden truths and questions hardened narratives.” The project allows viewers to see people as they see themselves. Its purpose? To encourage discussion and understanding in a time of heightened racial tension.

As its founding director, Norris oversees a team of four whom she calls “my tiny little army.” They manage an ongoing tsunami of emailed entries and help the project partner with corporations, government entities, and colleges that use its materials in diversity and inclusion efforts.

“I think it’s excellent,” says Professor Jennifer Edgoose, who heads diversity, inclusion, and equity efforts in the UW’s Department of Family Medicine and Community Health. Its doctors and staff are each creating race cards, which are then posted online for all to read. “It’s a great opportunity for people to write very thoughtfully and concisely in this space,” she says.

The submissions spill into commentary on religion, sexual orientation, heritage, and disability. They deal with every “difficult, dirty, prickly, complicated, and intricate emotion you can imagine,” says Norris. They include such confessions as:

“Being conspicuous is a daily struggle.”

“Black Vietnamese. Speak Spanish. Eat rice.”

“White female born in America. Blessed.”

“Apparently I’m Jesus or a terrorist.”

“White. Not allowed to be proud.”

“The plantation haunts my gay marriage.”

“Native Americans, America’s invisible invisible invisible.”

“I’m only Jewish when it’s safe.”

“Hated for being a white cop.”

One recent entry came from the great-grandchild of a conductor on the Underground Railroad.

“The everyday stories that land in my in-box every day allow me to talk to people I might never have otherwise met,” says Norris, who is now a national affairs columnist at the Washington Post and a storytelling fellow at National Geographic.

“How else would I talk to a cop in Nacogdoches, Texas; a trans teen in Wyoming; or a mom in Arizona who years ago figured out how to open her heart and her home to a child of color long before we saw multiracial families in ways we do now?” she asks.

Norris says she’s able to reach out and have in-depth conversations that help her understand an issue “that most often is examined on a huge national platform where people are debating or screaming at each other, as opposed to in the private and much more intimate spaces where people wrestle with these issues quietly. And that’s where I get to go, thanks to this project.”

“Snap out of it.”

That’s what Norris’s mother, who was also a book lover and postal worker, said when chastising her as a child. “My mother’s tough. Rock of Gibraltar tough. … She has no patience for ‘Woe is me,’ ” wrote Norris, who added, “I was raised by a model minority to be a model minority.”

But woeful is how Norris felt at the UW. She didn’t know how to snap out of it. She struggled in class. Her major was electrical engineering, a decision she made thanks to her prowess in a high school math and science program for minority students. “I wasn’t burning up the world to be an engineer,” she recalls. She was “very lonely” because there were few women (and even fewer women of color) in the program.

The turning point came when she overheard two friends in the library. “They were saying, ‘She studies so hard, but she’s just not a very good student. She just doesn’t do that well in school.’ That really shook me, because I was like ‘That’s not who I am. I’ve always been a really good student,’ ” she recalls.

With input from a UW dean and other professors, Norris took a political science class that got her excited about other options. Due to a speech impediment she suffered as a child (“My brain worked faster than my mouth,” she says), she had questioned how good a communicator she could be. But she changed her major to pre-journalism and soon transferred to the University of Minnesota. Back in the Twin Cities, she came alive. She took three jobs. She waitressed, wrote for the student paper, and held down the weekend graveyard shift at WCCO-TV, where she listened to police and fire radios and dispatched camera crews to cover breaking news scenes.

She benefited from insightful mentors. “You’re a pretty good writer,” her WCCO boss told her. “You just need to use fewer words, because it’s broadcast.” After graduation, at the Los Angeles Times, her editor said, “You have a way with words. If you work at your craft, you’ll be able to punch above your weight.”

Norris entered the heavyweight ranks when the Chicago Tribune took her on. Then when she was 26, the Washington Post hired her to cover education. After visiting a first-grade classroom, she took the bus home with Dooney Waters, “a thickset six-year-old missing two front teeth.” She found herself holding the reins of a multiday story that became national news. “6-YEAR-OLD’S MD. HOME WAS A MODERN-DAY OPIUM DEN,” read the Sunday edition’s front-page headline.

President Bush mentioned it. The Today show and other outlets wanted access to the boy and his family. “I remember at the time being very careful in protecting him and his family,” says Norris. She has kept up with Waters, who she says is a college graduate and “doing well.”

Then ABC News called. She found herself in 1993 covering the Clinton White House, an experience she calls “a high-wire-act platform. Once again, I was jumping into the deep end of the pool never having been on air.”

The experience frustrated her. “You have no access to the president other than waiting for him to walk by — usually on the tarmac — and yelling to try to get a one-line statement or going in the gaggle where he’s sitting down with a foreign dignitary. And the foreign dignitary is looking at the U.S. press corps like, ‘Oh, my gosh, you are the most uncouth and impolite group of humans I’ve ever seen,’ because you’re totally ignoring the dude in the chair next to the president and yelling questions at the president that have nothing to do with the country this leader represents.”

Norris says she has “yelled at both [President] Bushes trying to get answers.”

She found more satisfaction doing features for Nightline, Good Morning America, and World News Tonight. One producer taught her key storytelling techniques. “She always said, ‘Good TV is radio, because half the people who are listening to the evening news are doing just that. They’re chopping carrots and doing other stuff.’ I learned so much about how to punctuate a story with silences and ambient sound to make someone feel like they’re in an environment.”

Such lessons were priceless in 2002 when Norris became host of All Things Considered. “I had never ever worked in radio, and I walked in the door as a host. I had to learn how to put my ego in my back pocket and realize every single person I encountered could teach me something,” says Norris, who stepped away from her position in 2011 (and also refrained from covering politics) when her husband, Broderick Johnson, joined President Obama’s reelection campaign.

Norris interviewed notables who ranged from Afghanistan’s president Hamid Karzai to Robert De Niro. In 2008, she cohosted a presidential debate with NPR host Steve Inskeep. A candidate avoided answering her question. “So she asked a second time,” Inskeep recalls. “It seemed to me like it was time to move the debate to the next thing, but she jumped in and said, ‘I’m going to try this one more time.’ I thought that was Michele in essence, because she is gracious. She was courteous. She was precise, and she was tough. She wasn’t going to take a bunch of obfuscation, and I think that is what has marked her as a journalist and as a person.”

On other occasions, Norris displayed empathy that made her a better journalist, according to NPR executive producer Madhulika Sikka. When Norris interviewed a roomful of potential 2008 voters, she knew there would be tension. “She told me the best way people will talk together is when they break bread together,” Sikka recalls. “Let’s make sure we have a meal for everybody to get to know each other and just chat with no recording. To me, that was quintessentially her — her understanding of how to make people feel comfortable.”

Her most unforgettable stories more often came when she talked with everyday people. “Some of the more memorable interviews that live inside me were talking to people after Hurricane Katrina. Those are interviews I will never ever forget,” she says. “I tried to make my approach to journalism to figure out how to walk through a different door than every other journalist would, to find stories or people at the margins who can illuminate an issue or enlighten us about something because they’re looking at it or experiencing it from a different vantage point.”

One such moment came when she spoke with a local politician who had come out as trans and was losing her job as a result. “I talked to her the day this was happening,” says Norris. “It was an emotional roller coaster to give her the objectivity and dignity to tell her story, explore her employer’s point of view in a respectful, rigorous way, avoid sensationalism — and do it on deadline.

“That’s a real skill, but also a real thrill when you’re in the moment and your producer and director are in your ear,” she adds. “It’s like riding a rodeo bull.”

Today The Race Card Project has Norris on another wild ride. Besides producing spin-off podcasts, she is writing a book about collecting candid stories about race during the Obama–Trump years that will be published by Simon & Schuster. In the future, she hopes to partner with data scientists to catalog her vast collection to make it accessible to scholars.

Her sprawling, fast-growing project is not unlike gardening, Norris’s stress-reducing pastime — a hobby her father also pursued. “There are all kinds of metaphors in gardening,” she muses. “You’re taking care of something. You’re keeping something alive. You realize some things that are big and showy like peonies are beautiful but can’t even hold themselves up, and there’s a metaphor in that. The garden teaches you life lessons all the time, and it humbles you, and it surprises you, because you think something that shoots up out of the ground is going to be one thing, and then it changes.”

Of the more than 500,000 entries in The Race Card Project, Norris has changed one submission, the one closest to her heart — her own. Her first was “Fooled them all. Not done yet.” More recently, she says, “The one that I land on over and over again is ‘Still more work to be done,’ because we often want the sense we’re rounding the corner to being done, and we won’t talk about race anymore and won’t think about race anymore. That’s perhaps where the idea of America moving into a post-racial society was supposed to come from, but there’s no finish line on the horizon, I don’t think.” •

George Spencer is a freelance writer who lives in Hillsborough, North Carolina, and was the author of “Better Living through Technology” in the Winter 2021 issue of On Wisconsin.

Published in the Spring 2022 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.