One Little Problem with 5G Cellular Networks

Recent efforts to roll out 5G cellular networks have hit turbulence as weather experts voice their concerns about the networks’ potential to interfere with forecasting.

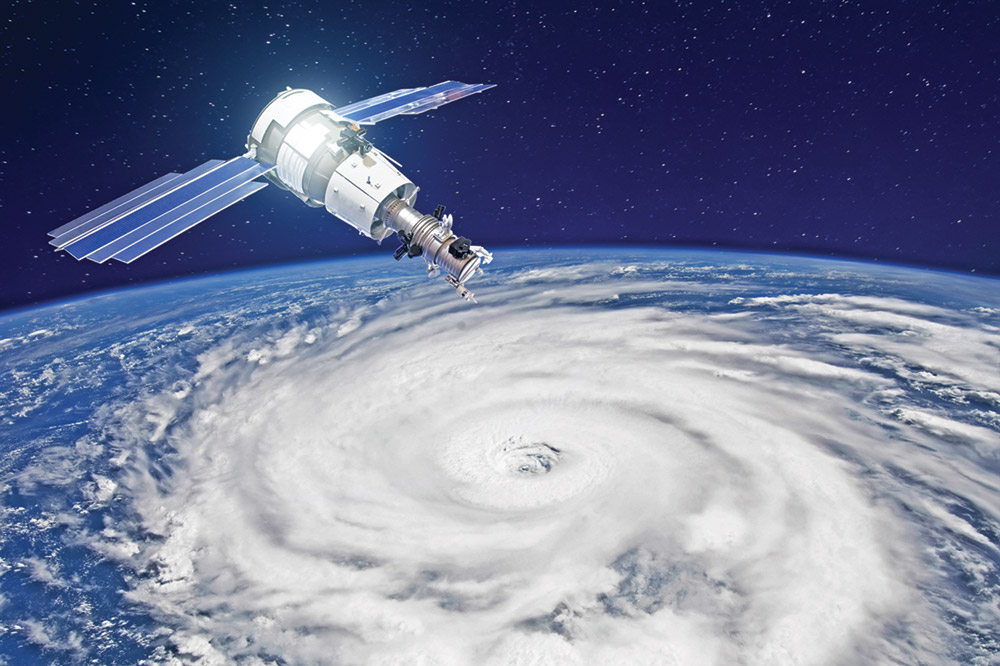

Jordan Gerth ’09, MS’11, PhD’13 is an associate researcher in the UW’s Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies and the chair of the American Meteorological Society’s Committee on Radio Frequency Allocations. He has spoken out on the topic in publications such as Nature and Wired, and he explains that two radio frequencies in the meteorological community face risk of interference. First is 23.8 gigahertz, which, for years, has been used by an instrument in the Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS) to sense water vapor, Gerth says. Collecting water-vapor data helps meteorologists understand and predict how weather patterns will evolve.

However, a neighboring frequency, 24 gigahertz, is one that 5G networks are hoping to use. Should the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) permit them to do so, 5G networks may overpower the nearby 23.8 gigahertz frequency and interrupt the detection of water vapor, meaning weather-prediction models could be inaccurate.

“Just like if you had an apartment building [with] a nightclub moving in next to a nursery for small children, that wouldn’t necessarily work out very well,” Gerth says. “Even though they’re in separate units, there’s going to be bleed-over noise [from one to] the other.”

As the FCC deliberates, one solution is for incoming 5G networks to turn down the power of the nearby frequency so meteorologists can still detect water-vapor information. This option, however, would require networks to reduce their power by about one thousand times, meaning they would likely need fundamental changes, Gerth says. He also notes that the meteorological community cannot switch frequencies without any impact.

The second band of frequencies — 1675 to 1695 megahertz — is used by another satellite, the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite-R Series (GOES-R), to transmit weather data to Earth. Some companies are looking to use a portion of those frequencies for their 5G services, running the risk that they will interfere with this transmission.

“When either the transmission of [the data] is interrupted, as is the case of GOES-R, or the collection of it is interrupted or interfered with, as would be the case with JPSS, it would interrupt that timeliness threshold that we have to provide consistent and reliable information about the weather to government agencies, airlines, and other weather-sensitive industries,” Gerth says.

Published in the Fall 2019 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.