An Ill Wind

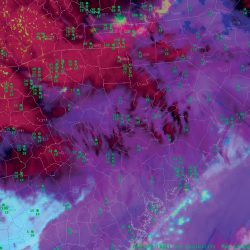

This image of Sandy was taken by one of NOAA’s Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites on October 29, as the storm neared the coast of New York and New Jersey. A time-lapse view of the storm’s development can be viewed online. Courtesy of UW-SSEC Data Center.

Superstorm Sandy shows the capacity of UW satellite science.

Last October, as Superstorm Sandy bore down on the coast of New York and New Jersey, national weather services relied on the UW’s Space Science and Engineering Center (SSEC) to get the satellite data that would help them analyze the storm’s behavior. Because meteorologists expected the storm to be so severe, SSEC asked the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to activate an offline satellite to follow Sandy exclusively, and send back minute-by-minute images. The result was an unprecedented dataset of a single storm’s lifecycle.

“We anticipated this potentially epic event coming up,” says senior scientist Christopher Velden. “So we asked NOAA if we could put one of our existing satellites into a special, rapid-scanning mode. They smartly agreed, and now we’ve documented this historical storm with continual, one-minute image sampling that provides a fascinating account of Sandy’s evolution.”

SSEC hosts the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies (CIMSS), formed in partnership among the UW, NASA, and NOAA. CIMSS scientists conduct meteorological research using images and information from satellites. “Minutes after a satellite picture is taken, it’s downloaded at SSEC and made available to the scientists here,” Velden says. The CIMSS team is then able to process the images into products that can help forecasters better predict what storm systems will do — such as charting the path that Sandy took out into the North Atlantic, and then back onto the shores of New York and New Jersey.

“We took the satellite imagery and turned it into hard data to help the Hurricane Center analyze the storm in real time,” Velden says. “We use the images to derive wind shear, steering currents, things like that. And that’s also the type of data that our [meteorological] computer models assimilate to predict the future storm track and intensity.”

Sandy also provided an opportunity to show what the satellites of the future will be able to do. Velden says the next generation of satellites — scheduled to launch in the next two to three years — will be able to routinely transmit such images at any time. This will enable meteorologists to home in on the factors that shape and direct severe weather systems, making forecasts more accurate.

Published in the Spring 2013 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.