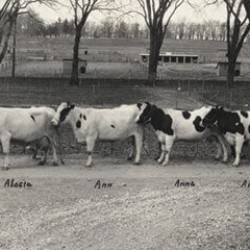

Contented Cows

A comfy space and familiar companions make for a healthier herd.

Cows thrive best when they have deep sand stalls and can hang out with friends, UW researchers have found. Photo: Jeff Miller

What’s the recipe for a healthy cow? UW-Madison veterinarian Ken Nordlund found a relatively simple answer: keep her happy with enough space and a soft cushion, and minimize social turmoil.

Dairy cows are incredibly vulnerable to disease in the weeks following the birth of a calf, and conventional wisdom used to be that when more than a few animals got sick, it was time to change their complex feed rations. But Nordlund says what researchers needed was an objective measure of cow health that would allow them to compare management practices with other dairies.

Nordlund and colleagues in the School of Veterinary Medicine worked for four years, using records for a half-million cows, to develop a statistical model called the Transition Cow Index. The record-keeping tool predicts a cow’s expected milk output during the first month after birthing a calf; the UW team used the resulting scores to develop concrete suggestions to help farmers improve the health of their cows.

Dairies with deep sand stalls that give cows more room to feed — so they can all eat at once rather than in shifts — and that keep cows in stable social groups have the best scores. Cows are social animals, a fact not always considered in modern dairy barn design.

“It just requires a change in thinking,” Nordlund says.

Since the index was first introduced in 2006, about two thousand dairy farmers, mostly in Wisconsin, have purchased the record system, patented by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and licensed to AgSource. A number of farmers even built brand-new facilities to meet the UW researchers’ recommendations, and Nordlund says the difference in productivity and health is astonishing. Farmers who have adopted the suggestions have seen significant drops in expenses for antibiotics.

“In general, dairy farmers want to do their very best for their cows, and if our work suggests that that’s what’s needed, many will say, ‘Okay, we’ll figure out a way to do that,’ ” Nordlund says. “It was more readily accepted than I ever expected.”

Published in the Spring 2010 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.