For all the right seasons

In theory, it was a simple idea back in 1934: set aside a place to study how both natural and human forces shape the land. In practice, though, saving the UW Arboretum is an ongoing challenge.

Whenever the pressures of daily life become too much, people come to the UW Arboretum. Whether in the golden warmth of autumn, the crystalline stillness of winter, or summer’s hothouse profusion of plant life, they seek and find tranquillity here. A calm descends that is the singular gift of natural places, far away from humanity’s dreams and cares.

This is what many of us cherish about the Arboretum: It seems a place apart. But it is not.

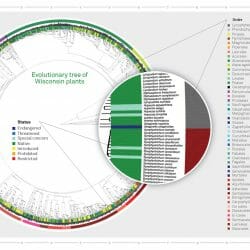

Rather, it has always been a center for two very human endeavors — teaching and research. Alarmed by the loss of Wisconsin’s prairies, woods, and wetlands, university and civic leaders dedicated the Arboretum seventy-five years ago as a preserve for vanishing landscapes and a place to study how to bring them back. Following famed conservationist Aldo Leopold, the Arboretum’s first research director, generations of UW scientists have since worked here, their tools and ideas eventually gelling into the science of restoration ecology. Beyond nature herself, we have them to thank for the vistas we so love.

But humanity’s reach doesn’t end there. As Madison’s growth has squeezed the Arboretum from all sides over time, other human forces have come into play. Though lacking the intention of science, they are shaping the land all the same — and revealing how tied to nature we truly are.

Spring: Gardner Marsh

A fresh crop of cattail leaves emerging from last year’s withered growth is one of the most emblematic sights of spring. And yet, these cattails are not natural denizens of Midwest wetlands at all, but instead an aggressive, invasive species and a sure sign of mankind’s influence over Gardner Marsh.

In the two decades before the Arboretum’s founding, developers drained, dredged, and filled the wetland for a new Madison suburb. Known today as the Lost City, the development ultimately failed, but its legacy lives on in the shrubs and trees that have invaded the higher, drier ground left behind. Water levels that are stabilized around the city to keep homes from flooding now flood sections of the marsh year round. This, combined with phosphorus-laden urban runoff, has allowed invasive cattail to consume nearly thirty acres of Gardner Marsh.

Today, only a tiny remnant of the original plant community — known as sedge meadow — remains, and Arboretum research director Joy Zedler MS’66, PhD’68 is bent on keeping it. Her former student, Steve Hall ’05, MS’08, found that cutting cattail underwater along its border with sedge meadow smothers the plant, allowing the natural community to reclaim about a foot and a half of land each year. For now, Zedler thinks this is the best that can be done. Trying to restore a larger area all at once would be too laborious and expensive.

It’s the same story throughout the Arboretum: beating back invasive plants has become the imperative. “Undertaking new restoration projects has gotten really difficult,” says Zedler. “It’s takes all of our field staff and volunteers just to hold the line.”

Summer: Greene Prairie

The solitude of sunrise over this land would have just suited Henry Greene. Beginning in the 1940s, the reclusive UW botanist spent countless hours at Greene Prairie, carefully examining the soil and moisture gradients, and placing prairie species such as white lady’s slipper, downy phlox, and bottle gentian into their natural groupings and local habitats. In the end, he created one of the finest restored prairies anywhere in the world. And he did it almost single-handedly.

How amazed Greene would be, then, to see what’s happening in his prairie today. Each September, a small army of UW ecology students has been helping with a restoration experiment aimed at saving his masterwork from another invasive plant, reed canary grass. Aided by stormwater runoff, the weed has devoured nearly ten acres of land, making the problem too immense for Arboretum researchers and managers to tackle alone.

Given the myriad challenges facing the entire preserve, Zedler would like to see many more undergraduates get involved. With hundreds — even only dozens — of helpers, she believes the Arboretum could make visible progress on a number of fronts, while also teaching generations of students about the loss of native habitats and just how difficult they are to bring back. The lesson is right here in Greene’s prairie. Even if the area can be rescued from reed canary grass, his painstaking plantings in the ten affected acres likely are gone forever.

“That’s the hard thing — I don’t think we could ever get back the full range of diversity,” says Zedler. “We can reestablish the most aggressive native species, the ones with the broadest range of tolerance. It’s the rare species that we don’t know how to recover.”

Fall: Curtis Prairie

The grasses in seventy-five-year-old Curtis Prairie still reach skyward every autumn, but they can’t stretch tall enough to hide another worrisome trend. This grassland, the oldest restored prairie in the world, is slowly becoming a shrubland. A small mountain of willow now looms above the prairie’s eastern end, while grey dogwood — a native, but aggressive shrub — has grown almost as abundant as the prairie icon, big bluestem.

It’s a puzzling development for the Arboretum’s managers. Nearly from the start, they’ve set regular fires to burn off shrubs and other unwelcome plants. Curtis Prairie is home, in fact, to some of the first experiments demonstrating the beneficial effects of fire. Seven decades later, however, fire doesn’t seem to be working anymore.

Paul Zedler, a UW-Madison environmental studies professor, Arboretum scientist, and Joy Zedler’s spouse, suspects that prescribed burns, which must be done for safety reasons during the cool, moist months of spring, don’t burn hot enough to kill shrub roots. Flows of nutrient-rich stormwater, the site’s legacy of farming — even global warming — could also be giving shrubs the edge. Or perhaps tall grass prairie always contained large patches of dogwood, sumac, and willow, Zedler muses, but settlers didn’t notice them as much when grasslands extended for hundreds of square miles instead of tens of acres. Whatever the explanation, Curtis Prairie is proving that, unlike a renovated painting preserved behind glass in a museum, “restored” nature is not so easily kept.

Few know this better than Steve Glass, longtime Arboretum land care manager. “The shrub invasion, of course, concerns us,” he says. “But in the face of climate change and the fact that ecosystems change anyway, we’ll have to keep learning and adapting. It’s how we advance restoration ecology.”

Winter: Leopold Pines

Climate change may eventually force adaptation of another kind. Aldo Leopold originally envisioned the Arboretum as a place to recreate ecosystems from all over Wisconsin — southern prairies to northern forests. But as the climate continues to warm, preserving Wisconsin’s most northerly plant communities here may not be feasible.

Take the Leopold Pines. Donated to the Arboretum as seedlings, the northern white pines, red pines, and spruces were planted in 1934 and named in honor of Leopold in 1953. Today many of these trees buffer Curtis Prairie from traffic whizzing by on the nearby Beltline Highway, but what of their future? Should they be maintained in keeping with Leopold’s vision? Or should that vision evolve in light of climate change and increasing urbanization?

As the Arboretum’s keepers contemplate the future, these are but two of the questions they face. Meanwhile, they’ve reluctantly reached one decision: in an attempt to cope with the half billion gallons of urban runoff that course into the reserve each year, dozens of acres are being given up to new detention ponds and other stormwater structures — in the hope of halting some of the damage to places like the Curtis and Greene Prairies. The projects also raise many new research questions, ensuring there will be “plenty to do” during the next seventy-five years, says Joy Zedler.

Yet, while remaining committed to building restoration science as a whole, she admits the great needs of this one beloved place can dishearten her.

“But then,” Zedler says, “I think, if there were ever a place where people care and where restoration is our mission, it’s the Arboretum.”

Published in the Fall 2009 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.