There’s an Apps for that

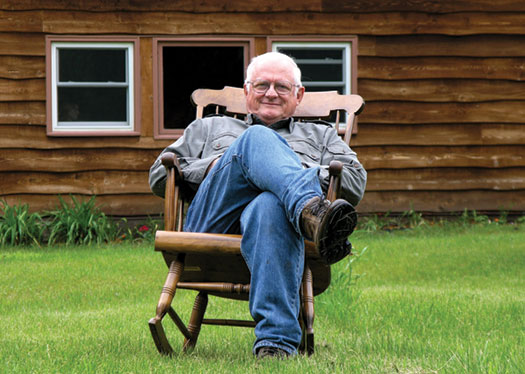

Jerry Apps finds his muse at the family farm near Wild Rose in central Wisconsin, where he goes “to find the country quiet that I love and need in my life,” he says. Photo: Steve Apps.

Name any topic pertaining to Wisconsin life and culture, and prolific author Jerry Apps ’55, MS’57, PhD’57 has probably written about it.

When writer Jerry Apps stands on his farm in central Wisconsin, he hears the sounds and remembers the stories of an earlier time.

He hears the rustle of the yellow heads of oats waving in the wind, the clatter and shudder of the threshing machine, and the rattle of dry corn leaves. Down the lane, he hears the clang of the bell announcing the start of the day at the one-room country school. The sounds spring from his memories of growing up on a nearby farm during the 1940s and ’50s. This rustic lifestyle is one he knows well, but it’s something he fears we may be losing.

Apps has devoted his career to recording and telling the stories of rural people and culture in Wisconsin. Driven to preserve and memorialize country life before it’s gone, Apps has written more than thirty-five books on rural history, averaging two new titles annually in recent years, with three or four books in progress at all times. He has “more ideas than life left to write them,” he says. He’s also written twelve professional books for educators and more than eight hundred articles. The word prolific doesn’t seem big enough to encompass him.

Apps is also an emeritus professor at the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences who taught in the Department of Continuing and Vocational Education. His writing has covered some of Wisconsin’s most iconic topics — from breweries, cheese, and the Ringling brothers, to barns and the restoration and conservation of his own farm, Roshara. He also teaches others how to write their stories at venues around the state, including The Clearing Folk School in Door County.

And for this work, he’s won a dedicated base of readers and more than two dozen awards from Midwestern publishers, foundations, and other organizations.

Nostalgia plays a role in his success. His fans share his yearning for red barns, country roads, front porches, and communities where time seems to move more slowly. But for Apps, it’s more than just remembering simpler times.

“Rural living teaches important lessons about the value of community and family, doing things for each other, being there to help so everyone succeeds,” he says. “It taught me about the relationship between humans and the land, and that’s a connection we have no matter where or when we live.”

Among the most important lessons he’s learned, says Apps, is the pervasive and profound influence of “nature’s clock.”

“In our hurry-hurry, electronically laced lives, we often think we can ignore nature, but it’s always there, shaping everything we do and everything we can do,” he says.

It’s not that rural Wisconsin’s biggest champion is against progress. “I believe the past plays an important part in shaping the future, helping us understand where we began and what mattered to us,” he explains, “so we can better understand if it’s worth throwing out and starting over, or making small changes to timeworn ideas to fit modern times.” Apps sees lessons from the past all around him. He points to the way that respecting the land was important to his family when he was growing up. “It’s how we had food on the table and a little money in our pockets every year,” he says. “There was a way we knew of living with the land that comes from country living. Taking care of the land is even more important today if we are to have food on all of our dinner tables.”

Apps believes this knowledge gained by living close to the earth — how people survived and thrived with nature — holds valuable insights into ways to care for the environment in the future.

“I always tell my writing students that when we forget our histories, we forget who we are,” he says. So taking cues from his own life, the author uses his words to transport readers beyond the pavement to the soil that shaped his view of the world.

“Jerry Apps’s work celebrates the rural heritage of Wisconsin that is such an important part of our collective past in this state,” says Kathy Borkowski MA’92, MA’95, director of the Wisconsin Historical Society Press, who has worked with Apps on several titles. “His stories provide a way for one generation to remember — and a way for another generation to appreciate — what makes Wisconsin the place we call home.”

With a steady stream of books, Apps is a frequent guest on Larry Meiller’s talk show on Wisconsin Public Radio. Meiller ’67, MS’68, PhD’77 calls him one of his most popular and effective guests because of his range of topics and good humor. As evidence, you need only stand in the studio and watch as lines of eager listeners form before Apps can even say hello.

“We’ve had joyous laughter from callers — and even some tears from some — who Jerry touched with his stories of a simpler life,” says Meiller. “He’s dedicated to preserving our heritage and to helping other people write about their lives.”

These are the types of stories and memories that Apps feels are vitally important to capture before they are gone. In all of his work, community, tradition, and roots are the dominant threads that underlie and tie the stories together.

These threads are also at the heart of good regional writing.

“Regional writing strips away all veneer of pretense and offers readers honesty and integrity, which arises, nearly, out of the land itself,” says LaMoine MacLaughlin, president of the Wisconsin Regional Writers Association. “It provides readers with a historical record and personal and human values, which Jerry Apps embodies perhaps more than any other living Wisconsin author.”

Sheila Leary, director of the University of Wisconsin Press, echoes that, calling Apps an authentic Wisconsin voice.

“Many themes and details in his work are inspired by experiences from his own life, but wrapped inside a good story are Jerry’s ideas about serious issues affecting rural life,” she says.

“Rural living teaches important lessons about the value of community and family, doing things for each other, being there to help everyone succeed,” says Apps, shown above working during a visit to northern Minnesota. “It taught me about the relationship between humans and the land, and that’s a connection we have no matter where or when we live.” Photo: Steve Apps.

I t’s easy to take farming for granted in Wisconsin. Forty percent of the state’s land is in agriculture. The landscape of plants and livestock, of farmhouses, silos, and barns, seems ever present. Nearly half a million Wisconsin residents work in agriculture, and it is deeply woven into the state’s history and traditions.

But this agrarian landscape is quickly disappearing. It’s not hard to be complacent about the future of rural life when the closest many of us get to a farm is the view through the windshield as we speed by. The reality is quite different. Wisconsin is losing farmland faster than any other state in the Midwest, nearly thirty thousand acres a year, most of it to development, according to the Wisconsin Academy’s Future of Farming and Rural Life in Wisconsin project. And with this land go the history, stories, beliefs, and values of rural communities that nurtured and sustained people like Jerry Apps.

The oldest of three siblings, Apps was born and raised on a 160-acre spread near Wild Rose, a small town in central Wisconsin, that his parents, Herman and Eleanor, bought in 1924. They worked their land through the Great Depression, World War II, and into the postwar years, when farming began to change dramatically with the rise of mechanical, chemical, and genetic power.

His childhood home “wasn’t a log cabin, but it was close,” laughs Apps. They had no electricity or indoor plumbing. Heat came from the wood stove.

As a kid, Apps milked cows by hand, made hay using horses and a pitchfork, and cut grain with a horse-drawn binder. The land didn’t relinquish its bounty easily. Located on the terminal moraine of Wisconsin’s last Ice Age, the acreage was hilly and the soil sandy and filled with rocks that had to be removed before the crops could go in. The future writer didn’t always relish the never-ending chores of his childhood, but the tradition, routine, and community fostered by the lifestyle stuck with him.

The appearance of tractors and other mechanical equipment on the scene spelled the end of annual traditions such as the neighborhood threshing crews that Apps worked as a teenager. Milking machines led to bigger dairy herds and bigger barns. Many older farmers retired, and their children left for the city and never came back. Operations grew in size as neighbors bought out their neighbors. From 200,000 farms in 1935, Wisconsin’s agricultural community shrank to 76,500 in 2006. Wisconsin has nearly 50,000 fewer farmers today than in 1970. Small communities lost their stores, schools, and churches as farmers left. Whole generations lost their connection to the land and the rural lifestyle of their ancestors.

Apps didn’t always appreciate the value of his own rural upbringing. Entering the University of Wisconsin in 1951 on a scholarship of $63.50, he quickly realized he came from a different world. The urban flurry of Madison unnerved him. His roommate, from the bustling metropolis of Rockford, Illinois, told Apps that even his walk was wrong. “You walk like you’re behind a plow,” he said.

“Bob,” Apps replied, “what do you think I was doing last week?”

Struggling to fit in, Apps worked hard to hide his country background. He studied the other students on University Avenue and learned to “walk city” as well as his classmates within a few months. No one would mistake him for a farm kid.

But soon after college, Apps realized that his background could actually be an asset, rather than a disadvantage. Serving as an officer in the army, he shared a tent at Fort Eustis in Virginia with a man from New York City who woke up frantic nearly every night at the slightest rustle, chirp, or howl from outside. Apps, on the other hand, found the noises comforting. They reminded him of home, even a thousand miles from Wisconsin.

“My time in the army made me realize that my roots were in the land, in my rural background and experiences, and I couldn’t deny that,” he says. Listening to his fellow officers brag about their urban hometowns, Apps recognized that his origins were not something to hide: he had just as much to be proud of as the next guy.

So he threw aside his city affectations, including that hard-won walk, and turned back to the rural roots and the people who had nurtured him. He began working with country people like himself, first as an Extension agent and then as a professor in the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences. He also began to tell stories to preserve and share his own memories, as well as the history of the rural Midwest.

The talented UW and Extension professor, folklorist, and author Robert Gard actively encouraged Apps’s writing. Gard was known for his activism in community arts and history programs, especially in rural areas. The two worked together at the UW, and Apps credits Gard with pressing him to tell his stories and to understand the importance of regional writing.

“Bob pushed me, gently but firmly, to do my best work, to capture the rapidly changing community and culture through my personal stories,” Apps recalls.

But Apps’s love of writing began long before that. Stricken with polio when he was only twelve years old, he began writing because he couldn’t move fast enough to play sports. Rather than merely being a hardship, though, Apps’s illness led him to realize the power of words. He became editor of his high school newspaper, joined forensics, and provided radio commentary during school basketball games. As an adult, Apps married his passion for speaking, writing, and storytelling with his belief in the importance of the past.

As more and more people live in urban places, the stories, values, and rhythms of country life grow increasingly distant. Wisconsin today is an uneven blend of city and country, as the state has followed national trends toward more urban and suburban living. Fifty-eight of Wisconsin’s 72 counties have at least a portion of their population categorized as urban, and 13 cities have populations above 50,000.

Apps himself lives a bit of a double life, spending a portion of his time in Madison and the rest on his sixty-five-acre farm just two miles from where he grew up. His father purchased the land and sold it to Apps and his twin brothers for $1 in 1966 to ensure that the family would stay strongly rooted. The family carefully restored the acreage and prairie — a tale Apps recounts, along with the genealogy of the land itself, in his book Old Farm.

“The farm is a place of solitude, where I go to find the country quiet that I love and need in my life,” he says.

It’s also how he stays connected to the land and where he taught his children to appreciate the value of a life lived close to the earth. Apps counts such great Wisconsin environmental thinkers as Aldo Leopold, John Muir x1863, Sigurd Olson ’20, and Gaylord Nelson LLB’42 among his heroes, because they taught him to recognize the importance of leaving something to the next generation. The farm has now become a touchstone for him, his wife, Ruth, and their three grown children. Apps often goes there to write and garden.

As in Old Farm, many of the rural historian’s stories and topics spring from his own life. Apps spent his first eight years of formal education in the one-room Chain O Lake school. That experience, and the realization that most of these country institutions had disappeared from the landscape, led him to write One-Room Country Schools: History and Recollections from Wisconsin.

“Wisconsin had over fifty ethnic groups, all committed to public education, in 1900,” Apps says. “The little country school was the symbol for accomplishing that, and was, along with the church, the cornerstone of the community.”

The consolidation of the one-room schools, along with agricultural changes in the latter half of the twentieth century, led to their demise. But for more than two hundred years, these schools were an integral part of Wisconsin life — as were small dairy farms.

In Cheese: The Making of a Wisconsin Tradition, Apps traces the history of cheesemaking from the 1840s to the present, exploring the evolution of the industry from the local farm to the factory. The same forces of change that drove many farmers off the land were also at work in the cheese industry in the twentieth century, as the small, family-run factory began to disappear.

Loss and change figure heavily in Apps’s Breweries of Wisconsin as well. Many of the beers he enjoyed as a young man in central Wisconsin no longer exist today. So he went back to the beginning to discover how breweries formed the core of many Wisconsin communities in the nineteenth century.

In recent years, Apps has also branched out to fiction. It’s not surprising for a man who believes that stories are the best way to teach history. While his novels focus on contemporary issues, each is deeply rooted in the past. His first novel, The Travels of Increase Joseph, was based on actual events that took place in Wisconsin in the mid-nineteenth century and featured an itinerant preacher with a guiding theology carefully crafted from all of Apps’s environmental heroes: Thoreau, Emerson, Muir, and Leopold. From this historical foundation, Apps wove a story of environmental conservation through the preaching of his fictional minister.

“All of my novels have a deeper message about something I care about, be it food safety or how to care for the land for future generations,” says Apps. “No one likes to be preached to, so why not try to convey a message through storytelling?

“Everyone should know where they came from — their history,” he says. “I try to capture the details, the beliefs, and values of rural and small-town people, what they did for fun and what was important to them.”

As rural life continues to change, Apps believes there’s no better time to explore the past — to remember who we were and what values we held dear.

“Every piece of land tells a story; every piece speaks its history,” he says. “The older I’ve gotten, the more I’ve realized that your history — where you grew up — it’s who you are today. It doesn’t matter if it’s the middle of New York City or a sandy farm in Waushara — that place creates you and underlies everything that you do and everything that you are and will be.”

Erika Janik MA’04, MA’06 is a Madison writer and radio producer who only wishes she were as prolific as Jerry Apps.

Published in the Summer 2012 issue

Comments

Cathy Zook June 1, 2012

I am one with nature !! Grew up on a farm near Alto WI. Now live outside Fond du lac and have a second farmette in the bluffs, Mondovi WI and that is God’s country. I have beautiful pictures of the bluffs, nature, sunrises, sunsets. It’s like being in a different world !!

Merlin Marquardt June 4, 2012

This is a very nice article about a man who seems to understand some important fundamental truths about life.

Barb Wolfe July 24, 2012

I would like to see an book written by Jerry on farming in southern wisconsin and coping with the changes and how we (I am one of those farmers) are trying to pass onto the new generation our farming way of life. I think it would help others understand what a farmer is coping with and why we hang onto our way of life as we do. Barb

Angeline Ibarra December 9, 2012

I am looking forward to seeing your documentary about farm life in Wisconsin.

I recently had a book published about a farming community in ND,’Tales of a Community That Was…”, Krassna ND, 1920’s to 1950’s. All the people were Germans from Russia.Their parents and grandparents had arrived in the late 1800’s from the steppes of Russia.Traditions passed down through gerations of a people who were first displaced from Germany and then from Russia provided us the strength to face the hardships of this new land.The isolation and the ability to cope with the harsh climate created a spporting community, where we attended a one room school house that allowed us to thrive. We survived.Today the community is a memory.

Looking forward to learn about your farming experience in WI compared to ND.

Chris Sass February 25, 2014

I am looking forward to reading your book about one rooms schools in Wisconsin. Read about your daughter’s book in the Juneau County Star Times but ordered yours as my mother was born in 1924 and attended a one room school. Still have a place up there and thought it would be a nice addition to our small library for my daughters and grandson to read. Still have her school report cards and graduation program. There were only 2 graduates that year and the other was our third cousin.

Jacqueline Bisaillon April 6, 2014

Just finished watching your special on channel 56 Indiana. My grandfather had a sister that lived and farmed in Wild Rose.Would you have any information on Len and Louise Gross?

I know almost nothing about them but that they were small farmers with a few dairy cows and chickens. Any information would be appreciated.

Jacie Bisaillon