Mind Tricks for the Masses

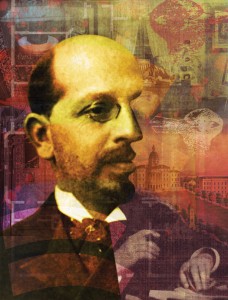

Joseph Jastrow, the feisty founder of Wisconsin’s psychology department, picked fights with everyone from Mark Twain to the UW president, but he was also a pioneer when it came to sharing science with the public.

December 1891 and Joseph Jastrow was finally, finally on vacation. True, he’d put it off until New Hampshire was icebound. But Jastrow, only twenty-eight years old and the founding head of the University of Wisconsin’s psychology department, had early earned his reputation for bullheadedness. He’d decided on a winter vacation in New England, planned out his route. He didn’t budge from his plans, as far as we know, until the day he idly picked up a copy of Harper’s magazine in a small-town library.

Psychology remained the bare dream of a profession that winter. The first psychology laboratory in the United States had been established just eight years earlier at Johns Hopkins University in 1883. Jastrow, a graduate of the program, was, in fact, the first person in the United States to have received a doctorate in psychology. His department at Wisconsin was barely three years old. The American Psychological Association didn’t exist. It would be founded in 1892 with exactly twenty-six members, including Jastrow.

So imagine the young psychologist’s dismay when he stopped at a New Hampshire library to check a map, picked up Harper’s, and discovered that one of the country’s most eminent novelists, Mark Twain, was making a mockery of the fledgling science. Or so Jastrow thought. Twain had considered his piece more positive. It hailed psychologists for their studies into telepathy and for making supernatural events valid research subjects.

Jastrow — as he later reported — read Twain’s article in a rising fury, tossed it down and rushed to the nearest telegraph office. He fired off a request to his own editor, at Scribner’s, to rebut the novelist’s claim. His article, which appeared the following month, dismissed Twain as a mere writer who had obviously been easily gulled by pseudoscientists. In regard to accepting telepathy — speaking for the view of mainstream psychology — “nothing could be further from the truth.”

—

That was Jastrow. Opinionated, arrogant, argumentative, irrepressible. A passionate public spokesman for his profession. A man who quarreled with everyone from his own university’s president to the author of the Sherlock Holmes stories, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (another misguided believer in the supernatural). A loving husband, a loyal friend. A star on the national lecture circuit, a mind-numbingly boring lecturer in his own classroom. A complicated man, Jastrow, as the influential behaviorist Clark Hull once wrote, was both “a unique personality and a truly historic figure from American psychology.”

Hull received his PhD under Jastrow in 1918 and joined the UW faculty, staying on until 1929. In a tribute to his former professor, Hull recalled some of Jastrow’s best research: work with sensory perception, visual illusions, the psychology of deception, the subconscious, and Freudian theory. But the man’s real interest, Hull said, was “a desire to make available to the literate masses the substance of scientific psychology.” His efforts in that regard “flowed from his pen in an uninterrupted stream.”

This dapper, driven, difficult man believed, far ahead of his time, that science should be shared with the public. He insisted that the study of human behavior was not an abstract academic endeavor but the stuff of everyday life. After he retired from the UW in 1927, he pushed that idea further, writing a nationally syndicated newspaper column, “Keeping Mentally Fit,” and becoming one of America’s first radio psychologists, hosting a show from the NBC studios in New York from 1935 to 1938.

Why didn’t he become a radio star in Wisconsin? Perhaps he wasn’t ready. More to the point, the university wasn’t ready. In the years before he left, Jastrow routinely complained that his pay was held below that of other professors. The dean of the College of Letters and Science replied that no additional money would be forthcoming to a professor who “had emphasized popularization at the expense of investigation.”

—

Above: Jastrow with his adopted son, Benno, who later died in World War I. Top: The Jastrows lived in two rooms in Ladies Hall when they first arrived on campus. State Historical Society.

Jastrow was born in Warsaw, Poland, on January 30, 1863. His parents, Marcus and Bertha Jastrow, moved the family to Philadelphia three years later. His father, a noted human rights activist while in Poland, flourished in the United States both as a congregational rabbi and an influential Talmudic scholar. Joe Jastrow — as he was known to his friends — preferred the explanations of science. He never lost, though, his respect for religion’s power to improve lives: “Fortunate are they who can use the path of prayer,” he wrote, adding that psychologists must also try to provide answers for “those who find their codes and creeds in other directions.”

He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1882, when he was just nineteen, going on to graduate school at Johns Hopkins. While in Baltimore, he lived with a friend of his father’s, Rabbi Benjamin Szold and his large family, which included eight daughters. One of Szold’s daughters, Henrietta, later founded the Hadassah Society, a leading women’s Zionist organization. She and Jastrow maintained a lifetime friendship, one only occasionally stressed by their differing beliefs. “A godless Darwinian,” she described him angrily during one such dispute. However, he was never quite so detached as that. He’d married one of the younger Szold daughters, Rachel, herself a Jewish activist.

Rachel had, rather practically, waited to accept Jastrow until he’d received his doctorate and landed a job (a starting salary of $2,000 from the University of Wisconsin). They were married in August 1888, shortly before moving to Madison. The Jastrows at first kept house in two rooms of Ladies Hall, an all-female dorm. A year later, they rented a house on Wilson Street and began making plans for building their own place.

When he first moved to Wisconsin, Jastrow blazed with research ideas. He invented an “automograph” — something like the planchette on a Ouija board — to make tracings of hand movements. He wanted to distinguish between voluntary movements and involuntary twitches. He studied hypnosis and introduced a course in the subject. He researched visual perception and invented optical illusions — known as Jastrow Objects — that can still trick eyes today. His neat, precise experiments gained respect from his peers; when William James published his seminal textbook, The Principles of Psychology, in 1890, he cited Jastrow twenty-five times.

In 1892 Jastrow agreed to organize the psychology exhibit at the Columbia Exposition, the Chicago World’s Fair scheduled to open a year later. He arranged to re-create famous psychology laboratories, borrowing brass instruments from Europe, charts from his fellow Americans, office furniture from one and all. He also used the exhibit to conduct experiments, running reaction-time tests on thousands of people who visited the pavilion. His reputation earned him a nickname from the UW’s literary magazine, the Aegis — “Psycho-Jastrow, the deep thinker.”

But trying to do everything brilliantly drove Jastrow to a breakdown. Depressed and ill, he received permission to take a leave of absence during the 1894–95 academic year. He would spend a good part of that time mulling over a choice. It seemed impossible to be both a dedicated academic and an advocate for public understanding of science. He didn’t have the time or the energy to do both.

He needed to decide which came first — or at least, which was more rewarding.

—

For all his argumentative edge, Jastrow could be a charmer. He might argue with authority, but he was exceptionally kind to people who worked for him. He cheerfully participated in local theater groups. He had a dry sense of humor and an easy sense of self-mockery. “Will wear any kind of clothes and eat anything,” he once wrote about himself. “Requires to be introduced to all captains of boat and train conductors. Is a good deal of a nuisance but doesn’t mind being told so.”

He was a small, balding man with a soft voice and steady brown eyes in a rounded face, ornamented by gold-rimmed glasses. “He smiled readily but rarely laughed,” a colleague recalled. He read constantly and was so aware of the complexities inherent in science that he found it impossible to answer a simple question. Students and faculty alike complained that his responses contained such a thicket of ideas that they almost never understood what he was talking about.

For all of his interest in public awareness of science, Jastrow showed no real enthusiasm for the classroom. His lectures were “frequently dull and uninforming,” Hull wrote, acknowledging that Jastrow’s focus on his university activities had steadily waned over the years. When his classes shone, it was because he was able to bring some exceptional guest speakers, such as his friend, the magician Harry Houdini. The two men had bonded over a shared interest in debunking fraudulent claims by spiritualists, and Houdini would do magic tricks in Jastrow’s classes to illustrate the art of deception.

But bringing in notable speakers did not pacify UW officials, who complained about Jastrow’s indifference to their expectations and the decline in his experimental work. Led by university president Charles Kendall Adams, the administration kept Jastrow’s salary depressed, offering annual raises of no more than $100 per year, and took punitive actions against his extracurricular work. One of the reasons that Jastrow had become so worn out during the 1893 exhibition was that the UW refused to release him from any teaching duties during the fair’s run.

Critics often described President Adams as arrogant and high-handed, pretty much the same complaints leveled at Jastrow. Competition and hostility simmered between the two men. When Adams arrived in Madison in 1892, replacing the more tolerant campus executive who hired Jastrow, he began by remodeling the modest president’s home, adding an expansive library room and decorating with Oriental rugs, antiques and oil paintings, statues, and costly silver.

The Jastrows had purchased a lot on Langdon Street, and they went on to build a two-story Queen Anne-style house there. It appeared to many to be a keeping-up-with-the-Adamses project, and the house was so expensive that it forced the Jastrows into near bankruptcy. Eventually, the couple added two more floors to serve as an apartment for themselves and rented out rooms in the lower two floors to pay for upkeep.

One of Jastrow’s research interests was visual perception, and he devised optical illusions known as Jastrow Objects that are still in use today. The top image can appear to be a rabbit or a duck, depending on how you look at it. In the bottom image, although the lower shape appears bigger, they are actually both the same size.

Jastrow — ever the popularizer — penned a story about their living quarters for House Beautiful in 1909. Each room in the apartment was decorated in a different style. The dining room was seventeenth-century Dutch with a pattern of antique Delft tile, the entry hall French Empire in style except for its Japanese gilt-cloth ceiling. In the attic, Jastrow had built an ornate Moorish study, hidden behind sliding panels and only accessible by a ladder. The study featured carved walnut walls, hanging lamps of pierced brass, a silver ceiling with a skylight glowing with amber and rose stained glass. (The house, which became the Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity house, was razed in 2009 after major destruction by a fire.)

He knew, of course, that the university would never provide the income to support his gorgeous home and growing art collection. Jastrow distanced himself even further from the campus, spending more and more of his time earning money by writing for popular magazines and by doing paid lectures around the country. On the lecture circuit, he proved that when he cared, he could be a lively and entertaining speaker, often drawing standing-room crowds.

In 1903, the UW downsized his title from professor of experimental and comparative psychology to professor of psychology. At that time, Jastrow was no longer doing any noticeable experimental work. He was, however, deliberately baiting Adams and his confreres, publishing article after article on the inadequacies of university administrators. In the Nation, Science, Century, the Educational Review, Jastrow repeatedly raised the question of whether college administrators really knew how to foster an intellectual environment. He warned especially against autocratic leaders, saying that the whole system was imperiled if it became undemocratic, if college presidents were allowed to become imperial presences on campus.

He would later publish a book, The Betrayal of Intelligence, that would encourage everyone — even college professors — to maintain an independent spirit: “Be critical — critical of what you accept, critical of whom you follow as authority.”

—

Of course, Jastrow was a born critic. It was one reason he became such a notable attack dog on the subject of supernatural research, taking on even his longtime friend and colleague, William James. James had become so fascinated with investigating the supernatural that he helped found the American Society for Psychical Research. Following James’s lead, Jastrow briefly joined the Society before quitting in a fit of exasperation.

He loathed the charlatanism of professional mediums with their séances held in the dark. He was contemptuous of people whose wide-eyed acceptance of floating tables and luminous ghosts fostered a lucrative trade. From his pen spilled a deluge of censorious articles, including his dismissal of Twain’s favorable review of telepathy. Years later, Jastrow summed up much of his writing on the subject in an article published in the intellectual review Forum, titled “Do the Dead Come Back? A Psychological Interpretation of Human Gullibility.”

But criticizing university administrators and combating spiritual credulity was only a small part of what Jastrow came to see as his public mission. He wrote books accessible to the general public: Fact and Fable in Psychology in 1900, The Subconscious in 1906, Character and Temperament in 1915. These were bookended by article after article for popular magazines, on comparative psychology, involuntary movements, animal intelligence, moral choice, the mental attributes of dictators, inherited intelligence, the criminal mind. In the latter, Jastrow directly took on the popular belief in genetic determinism. “The largest source of crime is misery,” he wrote in the North American Review.

In 1926, his wife, Rachel, died following a lingering illness. Jastrow did not stay in Madison long after. He retired from the university the following year, sold his beautiful house, and moved to New York. As he had once used the shock of his earlier depression to refocus his life, so again Jastrow moved to rebuild himself. Then in his mid-sixties, he took a job as a lecturer at The New School in New York City, where he stayed until 1932. “His health improved markedly and he threw himself completely into popular writing with a vigor unusual for a person his age,” Hull said.

Or any age. Jastrow published eight popular science books between 1928 and 1938, wrote his syndicated newspaper column, and broadcast a national radio show. At the time of his death on January 8, 1944, he was working on yet another book. As science historians have looked back at his life, many have remarked that he failed to live up to his promise as an outstanding researcher. They would be right, of course. But he gave his profession another gift, not well appreciated at the time, but equally enduring. He helped people see that the science of psychology mattered, that the science he loved could help illuminate the world in which we live.

Deborah Blum is a Pulitzer-winning science writer and a professor of journalism at UW-Madison. Her latest book is The Poisoner’s Handbook (Penguin Press).

Published in the Summer 2010 issue

Comments

Nina Farber August 30, 2012

Debra,

I thoroughly enjoyed your article about my great, great uncle Joe. I have been doing some research on this part of my family lately and would love to talk to at some point about anymore information you may have on him.

Nina Farber