Hard Truth

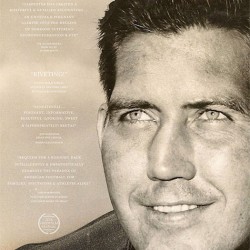

NFL star Chris Borland walked away from football to protect his brain — and to educate others.

Over the summer, Chris Borland ’13 attended the largest athletics fundraiser in Lawrence University’s history. He was an odd fit. There among players, coaches, and boosters was the “most dangerous man in football,” a nickname the former Badger star earned from ESPN after his unprecedented decision to leave the NFL over the long-term risk of brain trauma.

Borland made the trip to Appleton, Wisconsin, to support his new friend Ann McKee ’75, the night’s keynote speaker, whose brother was a star quarterback at Lawrence in the ’60s. To a stunned and largely unsuspecting audience, the foremost researcher on chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in football and other contact sports laid out her decade-long body of research on the degenerative brain disease that’s linked to minor, repetitive hits to the head.

Audible gasps interrupted the room’s silence when McKee projected side-by-side scans of healthy brains and brains riddled with damage. One had belonged to a 17-year-old high school football player who died by suicide and showed signs of CTE. “I’m not sure I’m giving the right speech for this crowd,” McKee confessed beforehand. By the time she was done, the night felt less like a celebration of sport and more like a cautioning of it.

As Borland was leaving, an attendee approached him. She wanted a picture to text to her partner — a huge football fan. “It’s ironic to me,” Borland says later. “Everyone tells me, ‘I loved watching you play at Wisconsin.’ And then they will say, ‘I really commend your decision [to leave football].’ ”

When you meet Borland, the unassuming history major sticks out more than the football player, with the wisdom and receding hairline of a man well beyond his years. His smile is welcoming; his tone is soft, reserved, and polite. He speaks with equal parts curiosity and conviction. Each word is carefully considered. He’s read hundreds of books since he left football. His word choice — from “disequilibrium” to “abyss” in a seamless sentence — bears it out.

Borland was born in Kettering, Ohio, a midsized suburb of Dayton. He was the sixth of seven active kids, with the oldest, a daughter, followed by six sons. They excelled in many sports growing up, except one: football. “I begged my dad to play every fall,” says Borland, who watched Wisconsin, Notre Dame, and the Green Bay Packers religiously.

Jeff Borland, who owns an investment advisory firm, played college football briefly at Miami University of Ohio. He was adamant that none of the boys would play organized football until high school. “I can’t say my concern was concussions — that would be too easy,” Jeff says. “It was more [broadly] head and neck injury based on the lack of form and technique.”

Borland fell in love with the game within five minutes of his first freshman practice. He took quickly to running back and receiver. On defense, his coaches designed a play for him — called “Badger” — to roam the field and target any player he saw fit. Once, he jumped and somersaulted over the offensive line, piledriving the running back into the ground in a single motion. It was violent — and it went viral.

The college recruiting process was brief. Borland’s dream school was always the UW. His grandfather, Henry Borland ’52, was an alumnus, and his father grew up in Madison. Most colleges projected him as a linebacker, even though he had never played the position formally.

Borland outperformed modest expectations and higher-rated recruits at his first two summer camps. His only preparation had been 20 minutes in a gym with his father, who relayed what he could remember from playing the position decades prior. By the end of a three-day camp at the UW — “When I showed up, they didn’t know who I was,” he says — head coach Bret Bielema saw enough potential to offer a scholarship. Borland jumped for joy — literally. He did a backflip in the Camp Randall parking lot and accepted the offer within an hour.

Borland went on to become one of the UW’s most dependable tacklers of all time. His aggressive, hard-nosed style on the field — combined with a school record for volunteer hours off of it — endeared him to fans. “You will be hard pressed to find a more genuine, empathetic human being,” said Kayla Gross ’15, community relations coordinator for UW athletics, in 2013.

Borland helped lead the UW to three conference championships, earning Big Ten Freshman of the Year in 2009 and Big Ten Defensive Player of the Year in 2013. His 420 career tackles rank sixth in school history.

During the 2014 NFL Draft, Borland’s reputation reigned. “He’s too short. He’s too slow. I don’t care — he can play,” proclaimed NFL Network draft expert Mike Mayock, describing Borland (endearingly, if later ironically) as a “thundering hardhead.” The San Francisco 49ers agreed, selecting him in the third round and signing him to a $2.9 million contract.

Coach Jim Harbaugh spoke glowingly of his middle linebacker throughout the year, telling reporters, “He’s so physical. You can see when he takes on the lead blocker that there is some rattling of fillings.” By season’s end, Borland led the 49ers’ top-five defense in tackles, was named to the All-Rookie Team, and was selected as an alternate for the Pro Bowl. He was just 24.

And then he walked away from it all.

Borland began looking into CTE during training camp of his rookie season. He had never given head injury serious thought until he ran head first into a nearly 300-pound fullback in practice. He almost certainly suffered a concussion, but he didn’t report it to the team, fearing that missing time could jeopardize his place on the roster.

Borland felt increasingly isolated in the 49ers’ locker room as he read A League of Denial. The book revealed the NFL’s resistance to acknowledging the link between football and CTE. When teammates and coaches were around, he hid it within another book’s cover.

Borland learned to compartmentalize. “I was living a very binary life, out of necessity,” he says. During practices, games, and training, his focus was remarkably singular. But in the back of his mind, he was thinking of his long-term brain health. And he was learning that with each collision he was compromising it.

Borland wrote a letter to his parents and handed it to them after a preseason game. It outlined his concerns and suggested that he might not be long for football. (Earlier in the summer, he had jotted down his career goals, including playing for at least 10 years.) They were surprised — and then relieved. Jeff Borland thought back to the UW days. His cousin, cheering emphatically, once remarked that the parents’ section at Camp Randall felt oddly quiet and dull. “What you’ve got to understand,” Jeff told her, “is we want them to do real, real well — and we want the team to win. But mostly we want them to be able to walk off the field at the end.”

Borland started with simple Google searches, then research papers, then books. He learned of the tragedy of “Iron Mike” Webster x’74, a star center for the Badgers who retired in 1990 after a Hall of Fame career with the Pittsburgh Steelers and Kansas City Chiefs. Legendary for his durability and toughness on the field, Webster later experienced chronic pain, dementia, depression, and homelessness. He died in 2002, becoming the first former NFL player diagnosed with CTE.

Borland went straight to the source: researchers. That’s how he met McKee, who leads the world’s largest brain bank at Boston University. She’s analyzed several hundred brains of former football players — far more than anyone else. She told him the hard truth.

By the end of his rookie season, Borland had seen, read, and heard enough. He was leaving football to preserve his long-term health. He informed the 49ers in March 2015, to the shock of teammates and NFL fans alike.

“It’s essentially heresy to walk away from football in America,” Borland acknowledges. Extreme fans called him, in the nicest of terms, soft and weak. Wrote one on Twitter: “All due respect to Chris Borland, and head injuries are no joke, but what a p – – – – .”

But to others, like David Meggyesy, Borland’s decision was a courageous act. Meggyesy would know: 50 years ago, he also walked away from the NFL in his prime. An outspoken civil rights advocate and Vietnam War critic, he was benched for silently protesting during the national anthem. He retired and released Out of Their League, a scathing account of racism, sexism, and abuses of power he witnessed in the NFL. After hearing Meggyesy speak at the UW in 2013, Borland picked up a copy of his book and consulted with him during his rookie season.

“When Chris retired, he had a lot of influence because he had such integrity and perspective about what he was saying,” says Meggyesy, who later worked for the NFL Players Association. “It was believable for a lot of people. He really loved to play the game. He was a hell of a player.”

If Borland had any lingering doubt, it disappeared in July 2017. McKee and her team at Boston University’s CTE Center had finished analyzing the brains of 111 former NFL players, ranging from ages 23 to 89. All but one showed signs of CTE.

The condition’s degenerative (and currently untreatable) nature means that the damage doesn’t cease even when the collisions do. CTE isn’t diagnosable in the living, but the symptoms often arise later in life, sometimes decades after the exposure to contact. The most common symptoms are memory loss, dementia, and behavioral changes such as aggression — similar to the effects of Alzheimer’s disease, but with different lesions and indicators in the brain.

TIME named Ann McKee as one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2018. McKee’s work was central to Borland’s decision to retire, and “she may have saved my life,” he wrote in the magazine. Dina Rudick/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

The research points to a numbers game. The more blows to the head, the more likely the disease. Notably, these include minor — or subconcussive — impacts. Because players rarely feel or show pain at the time of small, indirect hits, the damage is easy to ignore. But they add up to much more than the occasional big hit. Twenty percent of those with CTE never suffer a diagnosable concussion, according to McKee.

Critics are eager to point out the limitations of McKee’s research. Her work relies on donated brains. Families are more likely to donate their loved one’s brain if they had noticed signs of cognitive decline, and McKee readily acknowledges this selective sample.

But she returns to the numbers game. Some 1,300 former NFL players died over the eight-year span of her study. She has proof that 110 had CTE. Even in the unlikeliest event that not a single one of the other 1,190 former players developed CTE, the prevalence of the disease would still be close to 10 percent of all players. “That’s a public health problem,” she says.

When discussing her research, McKee oscillates between a rigorous scientist consumed with the hard data and a concerned citizen visibly affected by the human toll of CTE. To avoid preconceived notions, she analyzes each brain without knowledge of whom it belonged to. Afterward, for statistical comparison, she sets out to learn as much as she can. For hours on end, she listens as family members’ memories and stories turn to grief and anger. When McKee presents her research, she feels compelled to show more than the subjects’ shocking brain scans — she shows their smiling faces, too.

McKee, like Borland, no longer watches football. A lifelong Packers fan, her breaking point was Donnovan Hill in 2016. At age 13, he broke his neck and was paralyzed from a head-first collision while playing youth football. At age 18, he died from complications stemming from his injury. “That hit didn’t just cause paralysis,” McKee says. “He had tremendous brain damage.”

The current strategies to make football safer — better helmets, lower tackling, improved concussion protocols — might reduce some harm. But these ideas are rooted in a misguided focus, perpetuated at the very top of athletics, McKee says.

“The NFL has decided that this is a concussion issue, which it is not,” she continues. “It’s about the subconcussive, repetitive hits that happen with every collision.” Framing the issue around concussions, which can be managed and treated without fundamentally altering the sport, is a strategic choice.

According to McKee, the way to reduce the risk of CTE is to reduce collisions. In football, that’s no easy task. Collision is intrinsic; linemen surge together and crash helmets nearly every play. Fewer collisions translates to fewer practices, fewer plays, fewer games.

Ultimately, when Borland and McKee are asked how to make football safer, their answer is simple: football — at least the sport as we know it today — cannot be safe.

99%

Former NFL players with CTE (2017 BU study)

91%

Former college football players with CTE (2017 BU study)

21%

Former high school football players with CTE (2017 BU study)

Borland insists that he’s not anti-football. He’s pro-information. He wants players — many of whom remain “willfully ignorant,” he says — to learn the risks and to make informed decisions.

“I don’t [subscribe] to the notion that football is inherently evil or that there’s this impending doom and the game needs to go away,” Borland says. His primary concern is youth football, which often has the least regulated contact rules of all levels.

Earlier this year, he testified in support of the Dave Duerson Act, a proposal to ban tackle football for children under the age of 12 in Illinois. Those who started playing contact football before age 12 began to show signs of CTE an average of 13 years earlier compared to those who started playing later in life, according to McKee’s research.

Borland also volunteers for nonprofits dedicated to brain injuries in sports, including the Concussion Legacy Foundation and the After the Impact Fund. He travels and speaks frequently at conferences, and occasionally chats with players (including former UW receiver Jared Abbrederis ’13, who retired from the NFL in January) about his decision to leave football. Only a handful of NFL players have followed in Borland’s footsteps. That likely won’t change until CTE is more visible and can be traced in the living — which could be as soon as five years from now, McKee estimates.

The advocacy does not come naturally for Borland, who notes that the sport has afforded him lifelong memories and friendships. “I think the advocate struggles with [the question], ‘How much do I owe?’ ” Jeff Borland says. “As a parent, I would say I’m not sure he owes any more than he’s already done.”

While occasionally tempted, Chris Borland believes scaling back now would be a betrayal. “I’ve had wives of players tell me, ‘I wish he was dead, because he’s not the man I married, and I’ve just become a full-time caregiver for the last two decades.’ I can’t imagine saying no to someone who asks for something from that world,” he says.

In addition to the truth, Borland is searching for peace. The conversation surrounding safety in football provides anything but that. “The irony that I quit not to deal with this and [now], at least intellectually, deal with it every day isn’t lost on me,” says Borland. “And it’s tiring.”

Perhaps unintentionally, his favorite activities since leaving football share a common thread of escape: both physical, with traveling, surfing, hiking; and mental, with yoga and meditation.

Borland’s foray into mindfulness and meditative practice began when his brother-in-law gave him a copy of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, which prompted him to meditate “pretty clumsily.” Soon after, a mutual friend connected him with Richard Davidson, founder of the UW’s Center for Healthy Minds and a leading researcher on how meditative practices can affect emotional health and the brain.

Borland was immediately struck by Davidson’s candor and scientific rigor (something he particularly appreciated after being approached for endorsements of “concussion-curing” pills and other pseudo-therapies). For years, Borland had learned to train his physical body to prepare for the next play, but never his mind to prepare for what’s next in life.

The difficulty of transitioning from the intensity of professional sports to the slog of everyday life is well documented. Similar to military veterans, retired athletes can struggle with the sudden loss of structure, camaraderie, serviceable skills, and even a sense of identity. Daily meditation has helped him to work through personal anxiety and depression, and more simply, to relax and clear his mind. He thought it could help others, too.

Last spring, Borland and Chad McGehee, an instructor for the Center for Healthy Minds, collaborated on a first-of-its-kind meditative program for former NFL players. Seventeen participants met in Madison over a span of two months. McGehee taught them a new meditative practice each week and assigned a training plan for home. Although some of the former players were initially skeptical — particularly when they were handed a recruiting brochure titled “Love and Compassion Cultivation,” Borland says, laughing — many of them later reported that the practices helped them to sleep better and to manage stress and physical pain.

“One guy talked about how he trained as a football player at 1,000 miles an hour, maximum effort, all the time,” McGehee says. “But that same tenacity at all times didn’t serve him well [after] football. The way he put it is that [mindfulness] felt like a way of deprogramming some of those [tendencies], to become aware that they were there.”

Encouraged by the success of the pilot, Borland continues to collaborate with the UW’s center and also works with the Search Inside Yourself Leadership Institute, which teaches a mindfulness curriculum originally developed at Google. He’s facilitated meditative programs for teams at the UW, Michigan, and West Point, aiming to help active athletes cope with pressures on and off the playing field.

“The mindfulness [work] has been such a release valve for me,” says Borland, who now lives in Los Angeles. “It’s such a pivot to positivity and to optimism.”

When he meets former players, Borland pays special attention to how they introduce themselves. Some who have been retired from the NFL for as long as four decades will start with their name immediately followed by their past team or position.

“There’s a cliché that athletes live two lives: athlete and former athlete,” he says. “I don’t think it has to ring true. But it takes work to create a new identity.”

Preston Schmitt ’14 is a staff writer for On Wisconsin.

Published in the Winter 2018 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.