Head-On Collision

Ann McKee ’75 is discovering the dangers of contact sports, one brain at a time.

Ann McKee ’75 is at the center of a struggle between heart and head.

Her heart belongs to football. “I love football,” she says. “Everyone knows that. I come from a very heavily football family. My brothers played football, my father played football. I went to practices in the summer. I grew up in Appleton, and, you know, the Packers are pretty hard to ignore.”

Although she’s lived in Massachusetts for the last three deca des, spending her adult life in New England Patriots country hasn’t changed McKee’s allegiance. “I have rankings of my teams,” she says. “I love the Packers. I love Aaron Rodgers. I really don’t like Brett Favre.”

But McKee’s head belongs to science. As a neuropathologist, her chosen science is head science, the study of brains. And what her head tells her is that her favorite game is bad for its players — that football is literally beating some players’ brains into incoherence, and they won’t realize it until it’s too late to prevent an early and excruciating death.

“It’s very frightening,” McKee says. “Here’s this game that we all love so much, and though we don’t see any visible injuries, it can cause these devastating effects.”

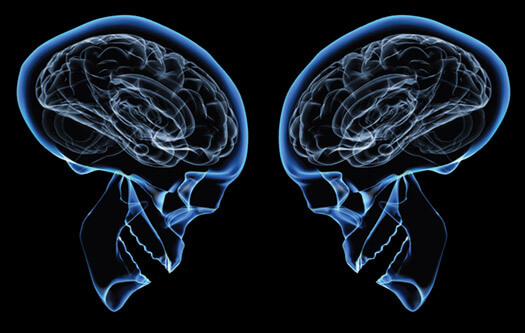

McKee knows this — and knows it with increasing certainty — because she’s seen the evidence under a microscope. She’s on the faculty at Boston University and runs the brain banks at the Veterans Administration hospital in Bedford, Massachusetts. There she autopsies the gray matter of the deceased to search for signs of neurological diseases and abnormalities. She’s examined the brains of dozens of former football players, boxers, and other athletes, and she and her Boston colleagues have published a series of articles that reveal and define the ravages that years of continual pounding can cause: a condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE.

CTE is insidious in that it seems to be caused by relatively minor head injuries — concussions and even sub-concussive hits to the head — that appear to pass with little or no short-term effect, leaving victims unaware of the difficulties to come.

“These individuals play their sport when they’re young, when they’re in their teens and twenties,” says McKee. “When they retire, which is usually in their thirties, they’re asymptomatic. They don’t develop symptoms until mid-life, late thirties and forties. And those are usually behavioral and personality changes, so a lot of people think they’re adjustment reactions or a mid-life crisis sort of deal. But actually, it’s neuro-degeneration. It’s an organic brain disease. It’s structural changes in their brains.”

McKee probably has more experience examining CTE-ravaged brains than anyone else in the world, and her studies are starting to change the rules and even the culture of football and sports in America.

Iron Mike

Mike Webster as a Badger: the Tomahawk, Wisconsin, native was drafted by the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1974 and played seventeen seasons in the NFL, leading to countless head injuries. Photo: UW-Madison Archives

McKee’s ranking of football favorites makes one glaring omission: the Wisconsin Badgers. But then her affinities were formed in her youth, and that period — the 1960s and early 1970s — was dominated by the Green Bay Packers: Vince Lombardi and Bart Starr, the Ice Bowl, and two Super Bowl victories. The Badgers offered nothing to compete.

“I went to school in the seventies,” she says. “It was total mayhem then. It was anarchy. I have only vague recollections of football.”

During McKee’s four years in Madison, the Badgers compiled a record of 19-24-1, with just one winning season. But despite their mediocrity, those Badger teams featured one of the best players in the school’s history: center Mike Webster x’74.

Certainly no Badger has gone on to greater success in the NFL. Drafted by the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1974, Webster became the anchor of that team’s offensive line, helping them win four Super Bowls. Nicknamed Iron Mike for his endurance, he played through injuries and started 150 consecutive games between 1976 and 1986, becoming one of the team’s offensive captains. Over the course of seventeen years in professional football, Webster built a resume that landed him in the NFL Hall of Fame in 1997.

But his career also brought less-welcome developments. The requirements of playing center — leaning over the football before passing it to the quarterback, then surging headfirst into oncoming defensive linemen, again and again, on almost every play — added up to countless instances of cranial trauma, as his brain was bounced around inside his skull hundreds of times every season.

By the time he retired in 1990, he was hooked on painkillers. By 2002, he was dead.

Webster’s passing was far from easy. He suffered not only from chronic pain, but also from bouts of amnesia, depression, and dementia. He spent periods living out of his truck or at train stations.

Still, Webster had one more contribution to make to football, though it wouldn’t come until after his death. His family had his body cremated, but his brain was sent to the University of Pittsburgh, where pathologist Bennet Omalu performed an autopsy. Though Webster’s brain at first appeared normal, Omalu discovered signs of the residue of a lifetime of physical trauma and diagnosed Webster with CTE, making him the first NFL player given that diagnosis. Since then, Webster has become something of a cause célèbre. His family sued the NFL for disability payments, receiving a judgment of over $1 million in 2006.

Webster’s diagnosis and the lawsuit helped raise the profile of CTE, but the disease itself is hardly a new discovery. The condition has been well documented for nearly a century, though under different names. It was first observed among professional fighters, who were described popularly as being “punch drunk.” The medical designation, first applied in 1928, was dementia pugilistica, or boxer’s dementia.

The disease typically first manifests as a loss of attention and concentration, memory deficits, confusion, dizziness, and headaches. As it progresses, victims may begin to show slurred speech, difficulty swallowing, drooping eyelids, deafness, slowed movement, vertigo, and a staggering gait. Ultimately, CTE can end in dementia, with victims suffering from poor insight and judgment, erratic behavior, and even psychosis.

CTE is not a common diagnosis, possibly because its symptoms are often masked by confusion with other neurological disorders. CTE involves memory loss, like Alzheimer’s disease, and diminishing muscle control, as in Parkinson’s and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig’s disease. But if the symptoms of CTE are difficult to recognize in the living, the evidence is unmistakable in the autopsy room.

Tau![]()

Ann McKee in the lab: by studying dozens of brains, she’s helping to discover the characteristics that define CTE. Photo: Kristin Pressly

Ann McKee’s first experience with CTE came in 2003, and it came as something of a surprise. She was autopsying the brain of a former resident of the Bedford VA hospital, a man who’d died at age 72, fifteen years after having been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

As with all her autopsies, she began looking at the brain before reading through the patient’s chart. “I always do the brain examination before knowing anything about the patient,” she says. “That’s a huge advantage. I’m able to look at the brain prior to being biased by any prior clinical information, so I go in with a more open mind.”

And an open mind was important when she opened up this patient’s brain, because she quickly determined that he didn’t have Alzheimer’s at all. One of the signs was there — the build-up of a protein called tau, which is supposed to remain inside nerve cell axons, but in Alzheimer’s escapes and becomes deformed and tangled, accumulating until it kills off brain cells. But other signs were missing — there was, for instance, no beta amyloid, a peptide that appears in heavy deposits in Alzheimer’s patients.

McKee found widespread damage across regions of the patient’s frontal cortex, temporal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala. “These are all important regions of the brain,” she says. “The frontal cortex has to do with intellect, insight, judgment, and multitasking; the temporal cortex with the same sort of things. The amygdala is the emotional part of the brain and governs rage behaviors and aggressiveness, and the hippocampus is a very important structure for learning and memory. All of these regions were very abnormal.”

She knew right away that she was dealing with something unusual, and when she read the chart, she figured out what that was. The patient had been a professional boxer — what she’d seen were the structural effects of dementia pugilistica, of CTE.

For the patient and his family, this had been tragic, but for McKee it was also fascinating. She’s spent almost her entire career delving into the mysteries of what makes brains functional and dysfunctional, and CTE, she believes, offers unique possibilities to learn about how brains work.

After earning her bachelor’s in zoology, McKee went on to medical school at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, before taking on three different residencies, in internal medicine, neurology, and finally neuropathology.

“There are a lot of fascinating systems in medicine … But there’s nothing that compares at all to the nervous system, because it’s so infinitely complex and anatomically diverse,” she says. “There’s so much we don’t know about what the mind is and what the brain is. It’s such a huge mystery.”

McKee’s career took the research route, with faculty positions first at Harvard and then at Boston University, and for the last twenty years, she’s focused her energy on neurodegenerative diseases. Currently based at the Bedford VA brain bank, she also heads the brain banks for Boston University’s Alzheimer’s Disease Center, the Framingham Heart Study, the Centenarian Study, and now the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy.

All together, these banks contain the brains of more than a thousand individuals. Removed from the donors’ bodies as quickly as possible after death, the brains are sliced into sections, with half of the tissue being frozen and the other half hardened with a fixative for immediate study. McKee then examines the brain tissue to try to diagnose any neurological disease — an examination that covers some 465 data points.

“It’s a huge, long process,” says McKee. “We look for all the proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease, or with the frontal and temporal dementias. We look for the proteins associated with ALS. It’s very comprehensive.”

And now her brain banks also check for CTE. McKee says she’s studied some thirty-six brains that show signs of the disease, not all of which came from athletes — some are from veterans who’d been jarred by explosions; some are from patients who’d had psychological disorders that drove them to repeatedly bang their heads. But most had been athletes competing in contact sports.

McKee has studied more athletes’ brains than any other neuropathologist, a record she credits to her connection with a professional wrestler.

Chris Harvard![]()

Chris Nowinski sustained several concussions while playing college football and wrestling professionally. AP Photo/Steven Senne

The same year that McKee performed her first CTE autopsy, Chris Nowinski also discovered the disease — and to him, it meant something far more personal.

Nowinski, a Harvard graduate, played football for the Crimson as a defensive lineman, and he took more than his share of hits to the head.

“I can remember one specific play where I was hit so hard I didn’t remember falling down,” he says. “I just remember opening my eyes and the sky had turned from blue to orange. Everything was tinted.”

Those head injuries didn’t end with Nowinski’s playing days, as after graduating, he went pro — but not in football. From 2001 to 2003, Chris Nowinski was known as Chris Harvard, the professional wrestler with an Ivy League pedigree. He did postgraduate studies at the World Wrestling Entertainment academy in Atlanta, and debuted in December 2001. As Chris Harvard, he wore crimson trunks, a letterman’s jacket emblazoned with a big H, and an air of intellectual smugness. His signature moves included the “Honor Roll” and the “Harvard Buster.” And before bashing his opponents with a folding chair or some such implement, he might quote Shakespeare.

He made a popular villain.

But for all Nowinski’s success in the ring, he was not immune to head trauma.

“I’ve suffered at least four concussions while wrestling,” he says, “perhaps more. There were times when I’d black out in the ring for about ten seconds and couldn’t remember what we’d planned for the rest of the match. In the summer of ’03, I had my last concussion, and my most severe. But because I didn’t know any better, I kept working out every day for five weeks. I had all sorts of memory and sleep issues just trying to push through it. And then one day I woke up on the floor of a hotel room having jumped through the nightstand in my sleep. That scared me straight.”

Nowinski knew that his brain was failing him, but he wasn’t sure just why. He went to see a series of specialists, including, ultimately, Bob Cantu, Bedford’s brain bank neurologist. Cantu suggested Nowinski was suffering the aftereffects of his head injuries and warned him about the dangers of CTE.

“I think Chris was so alarmed that so few people, even knowledgeable people, knew about [CTE] that he made it his life’s mission to understand concussion,” says McKee. “He wants people to understand the consequences of repetitive traumatic injury in sports.”

Nowinski dedicated himself to supporting research in CTE. He spoke with Cantu and with Bob Stern, a neuropsychologist, and in 2007, they encouraged him to meet with the person they convinced him was the best neuropathologist in the country: Ann McKee.

“One of the primary goals was to partner with a top-tier academic medical school to continue pathology studies,” Nowinski says. “But the research wasn’t being done to a standard that I believed was necessary to create change and find the cures that are needed.”

Nowinski, McKee, Stern, and Cantu formed a partnership to study CTE, and in the two years that they’ve been working together, they’ve found increasing evidence related to the disease. Cantu, according to McKee, “is the world’s leading expert on concussion,” while Stern studies the behaviors that lead to CTE, and McKee autopsies the deceased to find physical evidence. Nowinski uses his influence with other athletes and their families to spread the word on CTE and encourage brain donation, especially among former football players.

Throughout 2008, Nowinski convinced the families of several NFL players who died that year to donate those players’ brains to McKee’s lab: former linebacker John Grimsley, who died at age 45 after five years of cognitive decline; offensive lineman Tom McHale, who also died at 45; Wally Hilgenberg, who died at 66 in 2008 after having been diagnosed with ALS; offensive lineman Louis Creekmur, who died at age 82 after more than twenty years of dementia. All of them were found to have the widespread tau deposits characteristic of CTE.

“Every athlete whose brain Dr. McKee has studied who’s played more than ten years of contact sports has been diagnosed with CTE,” Nowinski says, which is not good news. At thirty-two, he can already see dark times coming. “I’d be naive to think that there’s not a good chance CTE is in my future,” he adds. “Statistically, it’s virtually guaranteed. The question is, how bad is it going to be, and is understanding it going to make it easier on the people around me?”

Defining a Disease

Currently, however, the group’s focus isn’t on treatment so much as on figuring out just how to recognize CTE in living individuals. The only means to reliably diagnose the disease is through autopsy, and no one, Nowinski points out, takes a disease seriously if it can only be recognized in the dead.

“Part of the problem is that until you have diagnostic criteria, you don’t really have a disease,” he says. “Nothing will be approved by the [Food and Drug Administration] or [Centers for Disease Control]. It can be a tough road to travel, but we’ll get there eventually.”

And so McKee’s work is only the first stage in combating CTE. As she collects the physical evidence of the disease’s effect on the brain, Stern and Cantu are trying to find ways to recognize those same signs in live athletes.

“We didn’t know what we were looking for before,” McKee says, “and the autopsies sort of laid it out: this is what this disease is. Now we just have to be able to look for those changes while the person is still alive.”

Stern is currently leading a longitudinal study of some three hundred athletes from around the country. All of them have agreed to donate their brains to McKee’s bank for study after they die, but that isn’t the primary focus of the work. “They’re young guys, so I certainly won’t be seeing most of these brains,” says McKee. Instead, the athletes are responding to regular surveys to monitor their injury history and to track their mental functioning.

Further, a subset of twenty athletes — ten with a history of traumatic brain injury and ten without — are undergoing more intensive study, including regular neuro-imaging tests, such as magnetic resonance imaging scans, and giving cerebrospinal fluid for chemical analysis.

The data that Stern generates, alongside McKee’s discoveries, may help create diagnostic criteria and uncover what sorts of triggers cause CTE — whether the important factors are moderate trauma, such as concussions, or relatively light trauma, such as the sub-concussive hits that don’t cause any recognizable symptoms at the time they occur and which are far more common. Professional football players on offensive and defensive lines, for instance, tend to suffer between nine hundred and fifteen hundred sub-concussive hits to the head each year.

McKee believes that medical science may be able to define diagnostic criteria for CTE in the living in the next two years. “I’m sure that we’re going to have a good handle on this,” she says. “Things are changing so quickly.”

Football

Not all of the athletes McKee and her group are looking at played football. In fact, her first major paper on the topic — “Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Athletes: Progressive Tauopathy after Repetitive Head Injury,” published in the Journal of Experimental Neurology in 2009 — cites fifty-one cases, only five of whom were football players. The vast majority — thirty-nine — were boxers. Why the focus on football now?

The answer lies in numbers. Football provides a lot of athletes to draw from. “It’s [the contact sport that] the most people are playing,” says Nowinski. “You’ve got the greatest urgency there, in that that’s where the most brain trauma is happening, and you can have the most impact in terms of reducing it.”

That large sample of football players may shed light on ways in which other groups of people are in danger of developing CTE. McKee notes, for instance, that members of the military may be at risk, due to proximity to explosions. “The VA has been very, very supportive of this work,” she says. “They’ve supplied nearly all the infrastructure for the brain bank. So we want to take what we’ve learned from the athletes and apply it to the military population, and hopefully come up with some answers.”

And then there’s the similarity between CTE and other neuro-degenerative diseases. Scientists have had a hard time studying the early stages of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS because those diseases’ development is unpredictable.

“In 85 percent of the individuals who develop these diseases, we have no idea why it happens,” says McKee. “There are about 15 percent of individuals who have a family history or have a genetic component. But there’s always been a huge subsection of the population who develop symptoms out of the blue. And here we have, in a population of football players [with CTE], an acquired injury, something they did to themselves or something they were exposed to that actually promoted a neuro-degenerative disease.” Studying those players, she hopes, may shed light on how Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS develop in their early stages, ultimately giving medicine a chance to treat such patients before their symptoms become too severe.

But most importantly, McKee and her colleagues are focusing on football because of its place in American culture.

“If football doesn’t change,” Nowinski says, “nothing else would change. If football didn’t see this as a problem, no one else would see this as a problem. Football is where you [change] the other sports.”

In the last year, the National Football League has given the CTE group at Boston University an unrestricted, $1 million grant to assist in their research. League leaders have met with McKee, Stern, and Cantu to discuss current studies, and the league also drew upon their research to launch a head-injury education campaign among its athletes, telling them of the signs and symptoms of concussion and warning them of the consequences of ignoring traumatic brain injuries. “Help make the game safer,” it says. “Other athletes are watching.”

If McKee can help football become a safer game, she can settle the struggle between head and heart. “Ultimately, we’re going to have to nip this in the bud,” she says. “Hopefully, a lot of it is prevention — changing the way the football is played, changing the culture, so that we’re not all an audience at the gladiator pit.”

John Allen, senior editor of On Wisconsin, hopes never to need Dr. McKee’s professional services.

Published in the Winter 2010 issue

Comments

John H. Tidyman December 25, 2010

Excellent story. Scary, too.

Jerry Colllins October 10, 2013

Kudos to Ann McKee. She has changed the way I will look at football forever. Not even sure at this point whether I can watch it.