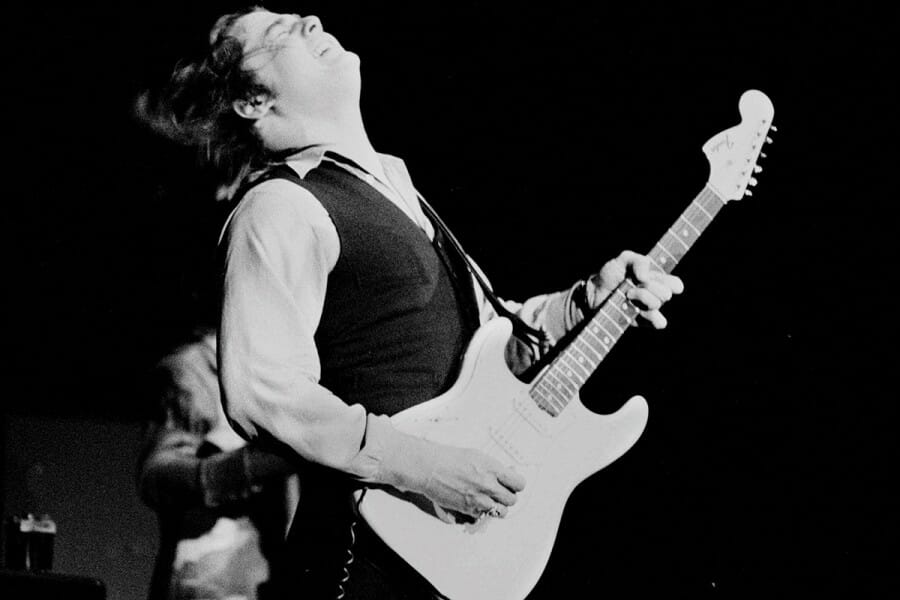

Keep on a- Rock’n Us, Baby

Steve Miller reflects on his 50-year career and campus in the ’60s.

Long before Steve Miller x’67 sang about being a space cowboy and flying like an eagle, he was a UW English major with a passion for civil rights. After growing up in Texas, Wisconsin was a homecoming of sorts for Miller since he was born in Milwaukee and spent his first five years in the state. More recently, he returned to campus during actual Homecoming in October, when he guest-lectured for a music class, performed a concert at the Memorial Union’s Shannon Hall, and directed the Fifth Quarter after the football game. One of Miller’s early influences was his godfather, acclaimed musician and inventor Les Paul, who became a friend of his parents when they lived in Waukesha, Wisconsin.

What are your favorite memories of Les Paul growing up?

Well, Les was one of the best guitar players ever. And he was always so generous. He taught me my first chords. He would always invite people to come and play with him — all kinds of people across all different generations. I think that was one of his greatest attributes — his openness to all kinds of music. You’d see Tony Bennett come up and sing a song with Les, and the next artist might be Jimmy Page or Keith Richards or Johnny Rotten or somebody you never heard of. He was very generous with the spotlight on his stage. That was my favorite thing.

Why did you decide to go to the UW?

I had a cousin there in graduate school. I had friends there. It had a wonderful reputation and great history and English departments, and I was very interested in creative writing and comparative literature. And also, it was really far away from home, and I wanted to get the hell out of town.

Did being an English major influence how you thought as a songwriter?

Yes, because it was basically comparative literature. The more writers you read, the broader your thinking becomes. That was part of it. But while that broadened my vision and ability to write, I was probably more influenced by blues artists and rhythm-and-blues artists and country artists — you know, the actual songwriting.

What UW lessons have informed your career?

The things I really learned there were when I joined SNCC [the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] and became a Freedom Rider. I was in the civil rights movement. And I was involved with the antiwar movement. That was probably the greatest thing I was exposed to, that there were activists on the campus, and it wasn’t something you [just] read about. You could go to a political gathering and get a different view than the standard view in the newspaper. If you felt as I did — very disturbed by the condition of blacks in America — and you wanted to fight for civil rights … that was the important part for me. It was more the political atmosphere on the campus than it was actually the classes I was taking.

You first met Boz Scaggs x’66 when you were in Texas, right?

Boz and I went to the same school, and when I was in the seventh grade, I started a band called the Marksmen Combo. And in the eighth grade, I asked Boz to join it. Boz and I played together all through junior high school and high school. Boz was a year behind me in school. He came up to the University of Wisconsin, and we played together there as well [in the Ardells]. We grew up together playing in the same band.

What was it like playing with the Ardells?

We were really a shuffle blues band. At the time, there really weren’t any rock ’n’ roll bands. There was maybe one other band on campus at the time. So we played all the parties — all the sorority parties, all the dorm parties, just everything. We backed up artists that came through town to do shows at the Coliseum. Those guys were all terrific, and Boz and I did the vocals. It was two guitars, bass, and drums. We were pretty funny, too, and really enjoyed playing.

What are some of your favorite memories of playing with them?

We usually played five times a weekend. In the afternoon, we’d play a beer supper, we’d play a fraternity party, before the football game, after the football game. Our last gig as the Ardells, I think we played “Louie Louie” 24 times in a row because we knew that was our last gig.

Why did you decide to go into music full time?

My mom and dad came to Madison and had a meeting with me. I had entered school when I was very young — I was 16 when I started my freshman year. So I was 20 years old, and my parents came to see me and said, “Steve, what are you going to do? Like what’s going on?” And I said, “Well, I want to go to Chicago and play blues.” It’s the last thing a parent wants to hear from their child. My dad gave me a look that said, “Nuh-uh.”

But my mother said, “You know, it’s a great idea. You’re young. You don’t have any responsibilities right now. So why don’t you go to Chicago and see if you can make something of your music. Just try.”

And honestly, the next 10 years were really rough. But for some reason, I believed in my ability and in myself. So I went to California and started a band, and we started managing ourselves and designing our stages and creating things. I was part of a group of people that changed the way people listened to music. When you come out to Summerfest and see that big stage and PA and those groovy lights, and things sound really great, that stuff all had to be invented in the late ’60s and early ’70s. It didn’t exist. It was a really exciting time because it was a real leap of faith. There was no set path. The path before that was to be on the Dick Clark show and get in a bus and ride around with seven other bands and play three songs on a show Dick Clark presented. And they owned all your publishing and work and everything. But we changed all that and turned it into a whole new world.

You’ve lived in and played places all over the world. Has that nomadic style of living affected you?

I go to about 70 cities a year and have for about 50 years, so I’ve been all over the United States and Europe and Australia. My wife and I really enjoy it. We like traveling and have friends all over the world that we visit and see.

You currently serve on the welcoming committee of the Department of Musical Instruments of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and as a board member of Jazz at Lincoln Center. What have you enjoyed most about those experiences?

The musical instruments department is one of the most fun places in the whole museum. They have the first piano and things like that. We’ve done two exhibits on guitars at the Met, and they’ve been very successful — 500,000 people came to each one. So that was a big deal.

I was asked by Wynton Marsalis to design the blues program at Lincoln Center. They wanted to start teaching blues like they do jazz. My wife, Janice, and I curate shows on jazz at Lincoln Center. We work on 12 music-education programs. The most important one is for children from the ages of eight months to three years. We’ve had metrics on those kids for 25 years. And it’s a very serious educational program as well as one of the great music venues.

For me, it’s a wonderful opportunity to work with really brilliant musicians and very smart people. At this point in my life, instead of retiring and playing golf, I’m being challenged, and I’m very enthused about the creativity that’s required of me to work in those environments. … It allows me to use my experience that I’ve gained over my lifetime and apply it to educational systems. When I’m [not touring], I work at Jazz at Lincoln Center and the Met. I’m thankful that somehow fate has washed me up on those shores. I’m giving them all I have, and will continue to do so until I leave the planet.

You were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2016. You were critical of it at the time. What do you think now?

The people who run the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame are well meaning. In my year, my induction, there were actually no ceremonies for anybody. We were just told to show up and do a television show. That was it. They’ve changed that.

[Now] they’re trying to do a lot of good programs. The music-education programs should actually make a difference and should have a goal. [The Hall of Fame] should be in Cleveland, not New York. They should keep track of the metrics. I think it’s going to be more inclusive and, in the end, will become a beacon of light for music education. That’s what it really should be. It’s drifting that way.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Joshua M. Miller (no relation to Steve). Joshua has written about music and entertainment for the Chicago Sun-Times, Paste, and a variety of other publications.

Published in the Spring 2018 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.