The Changing Face of Publishing

The publishing industry is going through radical changes, and the UW Press is adapting to preserve its mission and protect its bottom line.

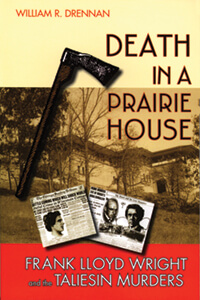

Once a day, sometimes more often, William Drennan sits down at his computer, directs his Web browser to Amazon.com, and punches in the title of a book he does not intend to buy: Death in a Prairie House, by William Drennan, published by the UW Press in 2007.

“I like to check its status,” he says, and he’s seldom disappointed. “It’s consistently the number-one nonfiction book on Frank Lloyd Wright.”

Death in a Prairie House tells the story of the brutal murders of seven people — including Wright’s mistress, Martha Borthwick Cheney — who were hacked to death with an ax at Taliesin, Wright’s home near Spring Green, Wisconsin, in August 1914. At the beginning of 2010, the book was not only Amazon’s top nonfiction seller on Wright, but its twenty-fourth-best-selling biography of an artist or architect, its fifty-first-best-selling true crime book, and number 31,200 among sales overall.

And one other thing: it’s the top-selling book the UW Press published in this decade.

Drennan uses Amazon to check on his book not only because it’s convenient — it’s also authoritative. Amazon sells more books than any other store, chain, or outlet on Earth. Amazon’s dominance of the book-selling world is a sign of the new age of publishing. An industry once based in paper and blue editorial pencils has been transformed by digital sales, digital warehousing, and digital books. To survive, those who create books — especially small publishers such as the UW Press — must explore new methods and new formats.

“Scholarly presses are going through a transition,” says UW Press director Sheila Leary. “Not only is there more electronic publishing, but the ways that classes are being taught are changing. The ways libraries operate are changing. The retail book business is in a radical transformation. We have to try a lot of new things and figure out what works. To survive, we need to publish many different kinds of books, deliver them in a lot of different formats, and sell them through a lot of channels.”

If you didn’t know the UW has a press — let alone what it publishes — you’re not alone.

“It’s funny,” says Raphael Kadushin ’75, MA’78, “but some of the press’s books may be better known nationally than here in Madison.”

Kadushin knows the press’s reputation better than almost anyone. His time on the staff spans three decades, and as one of its two acquisitions editors, he’s something of a guardian of that reputation — he seeks out the manuscripts that the press publishes, and he nourishes relationships with authors and reviewers.

Kadushin acquired Death in a Prairie House for the UW Press. “It’s in some ways typical of our regional list,” he says, “which really explores the history and culture of Wisconsin.”

These are the books that are best known locally — regional-interest titles, such as James Norton ’99 and Becca Dilley ’02’s Master Cheesemakers of Wisconsin, a photo-and-essay collection covering some of the state’s top dairies, or Jerry Apps ’55, MS’57, PhD’67’s Wisconsin-based novel, Blue Shadows Farm. In the publishing world, these are classified as trade books, ones that are written for and marketed to the general public.

Though the UW Press may have a low profile on campus, it’s been part of the university — or of the Graduate School, specifically — since 1937. Over three-quarters of a century, the press has built a reputation for producing deeply researched scholarship. It’s in this role, Leary feels, that the press serves its most important purpose.

“University presses fill a vital role in the academic world, and particularly within the humanities,” she says. “Professors need to publish their research, and they need textbooks for their classes, but a lot of those books wouldn’t be published by anyone else. They’re too narrow in focus, or aren’t likely to make enough money to interest commercial publishers.”

Like most university presses, the UW’s is mission-driven, meaning it defines success not just by its financial statement but by its goals, which Leary says are threefold: to publish scholarship for a worldwide audience, to document the cultural heritage of the state for its citizens, and to publish books that contribute to a literate culture and an informed citizenry.

This wasn’t always the press’s mission, however. When it was founded, its purpose was to get the work of the university’s own researchers — and particularly its scientists — into print. This is why it’s part of the Graduate School. The first book it published, by chemistry professor Homer Adkins, was titled Reactions of Hydrogen with Organic Compounds over Copper-Chromium Oxide and Nickel Catalysts (ranked number 5,482,944 in sales at Amazon).

But over the decades, the UW Press found its niche primarily within the humanities and social sciences. There, it can publish books that might not sell a lot initially, but which have staying power. Thus the focus on the humanities — in the sciences, medicine, and technology, many publications have a short shelf life.

“University presses exist by being very specific and knowing their niches very well,” says Leary. “In science and medicine, it’s difficult to be competitive. The information changes rapidly.”

Though the press does publish in some science niches, such as regional field guides and UW professor Bassam Shakhashiri’s Chemical Demonstrations volumes, its established expertise today is in other subjects, where Kadushin and his fellow acquisitions editor, Gwen Walker MA’93, PhD’06, work with UW faculty to find authors and evaluate works.

In 2009, the press published seventy-nine new or revised books, and it plans to publish about the same number this year. Subject areas include two distinct series in African studies, one general and one on women in Africa; Slavic and Eastern European studies; studies in American thought and culture; Southeast Asian studies; environmental studies; Jewish studies; European intellectual history and culture; Irish history; classical studies; history of dance; folklore; film studies; gay and lesbian studies; memoir and autobiography; and human rights.

In these areas, Leary notes, a book “is likely to be as relevant in fifty years as it is the day it’s first published.”

At first glance, the UW Press doesn’t seem like it’s facing digital upheaval. It occupies a warren of rooms in the Monroe Building, about a mile south of central campus, where every desk, shelf, closet, and cubicle is buried in piles of paper. Chairs there aren’t for sitting in but rather for stacking on: books, manuscripts, reviews, sales reports — the paraphernalia of nearly three-quarters of a century in the paper-usage industry.

But the value of the press isn’t found in its paper — it’s in that three-quarters of a century.

“Our biggest asset is our intellectual property,” says Russell Schwalbe ’88, the press’s business manager. “Our goal is to leverage the backlist and get as much value as we can out of it.”

The backlist is the collection of books — now about three thousand — that the press published in the past, as opposed to new books (i.e., its “front list”). To see the backlist’s value, consider Paul Mac-Kendrick’s Classics in Translation, volumes I (ancient Greek) and II (Latin), first printed in 1959. By Amazon’s standards, neither book is hot stuff, with sales rankings of 457,478 (volume I) and 929,673 (volume II). But together they’ve sold some 119,958 copies over the course of half a century, making Classics the press’s number-one title.

The point is not that UW Press titles sell poorly on Amazon — they do, but only because Amazon is just fifteen years old. The point, rather, is that the UW Press expects its books to sell very nearly forever, because the longer they sell, the more likely they are to become profitable.

“We expect our books to have a very long tail,” says Krista Coulson MA’06, the press’s electronic publishing manager.

Coulson’s office at the UW Press has nearly as many stacks of paper as anyone else’s, but it has one thing the others don’t — a Kindle. The Amazon e-book reader — which is loaded with a few titles, including Drennan’s Death in a Prairie House — serves a variety of purposes: it’s something of a curiosity, an experiment, a toy. And it’s a time bomb.

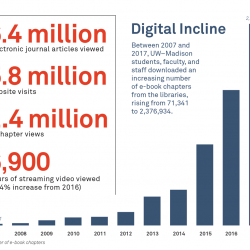

Amazon is using its dominant position to foster the growth of e-books, and 2009 was a banner year for digital readers. Amazon saw Kindle become its most-popular product, and industry analysts estimate 2 million units were sold last year. Other companies, including Sony and Barnes and Noble, launched competing e-book devices, and Apple joined the fray in 2010 with its iPad.

Amazon’s push to sell the Kindle in particular and e-books in general has the potential to wreak havoc across the publishing industry, and it’s Coulson’s job to find ways for the UW Press to harness that chaos, not be blown up by it.

Relatively inexpensive to produce, warehouse, and ship, e-books present new possibilities for academic publishers, especially with the classroom market. Consider UW history professor Jeremi Suri, for example. During the fall 2009 semester, he experimented with assigning a Kindle to every student in one of his classes, so that they had to carry only one device instead of eight weighty tomes.

Further, e-books offer the possibility that professors can tailor their own textbooks by loading a reader with chapters or sections of various books. Called disaggregation in the industry, the process offers a new way to gain revenue from books by licensing parts of them.

“It really gets into the idea of the long tail,” says Coulson.

She was hired into her current position in 2006, and so far, the UW Press has just begun to explore e-publishing. Death in a Prairie House, for example, has sold more than 18,000 copies in hard cover and paperback. But its sales as an e-book, while tops among UW Press titles, are more modest: 278.

“We have very little data so far,” says Coulson, “but what we’re seeing seems to show that the books that sell best in traditional formats are also the ones that sell best digitally. These aren’t academic books but rather bestsellers.”

Her initial work has been to go through the press’s backlist to select titles that are likely to sell well. So far, the press has made digital versions of some 350 of its books, focusing on the ones that have sold the best over the last decade.

In fall 2009, the press published electronic versions of many of its books at the same time that it released paper versions. Still, Schwalbe puts digital sales expectations in the hundreds, not the thousands.

The relatively small numbers and the press’s tight finances mean that Coulson and her colleagues have to be careful about following where electronic publishing — and any experimentation — leads.

“Whenever you’re talking about a new distribution channel, people get nervous,” she says. “We have to be sure that e-books don’t just cannibalize our paper books. The thing about university presses is that there’s not a lot of room for risk. In general, we’re strapped for cash.”

For Sheila Leary, this risk is necessary, and may give the UW Press more options for fulfilling its mission. Her take is positive: “Let a thousand formats bloom.”

John Allen is senior editor of On Wisconsin.

Published in the Spring 2010 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.