The Tug of War

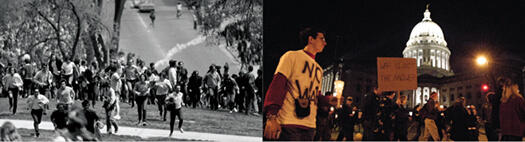

It’s a study in contrasts: Protestors against the Vietnam War ran from tear gas on Bascom Hill in the spring of 1970 (left), when a culmination of factors led to a week of campus protest — and a return of the National Guard. In recent years, demonstrations against the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, including a candlelight march at the State Capitol in 2003 (above), have been peaceful. Photos: (left) UW-Madison Archives; (right) Michael Forster Rothbart

Two eras, two altogether different pictures. Veterans returning to campus from Vietnam forty years ago were met with tear gas and derision. Today’s student veterans are often finding respect and a willingness to hear what they have to say.

UW-Madison has a reputation: anti-war, anti-military, and radical.

Say “Madison” and images of protest, violence, and unrest rush to mind. That was immediately apparent to Jeff Kollath when he visited some Wisconsin communities in 2009 to promote a Wisconsin Public Television documentary about Vietnam veterans that debuted in May.

Kollath, curator of programs and exhibitions for the Wisconsin Veterans Museum, noted a pervasive anti-Madison feeling among some veterans when he described an exhibit featuring portraits of Vietnam veterans at the UW’s Chazen Museum of Art. He marveled to one audience, “Who would’ve thought this would be on campus?” One man responded, “Hmph. It’s still Madison.”

But the pictures that cemented that status are decades old. A new reality has emerged for the more than six hundred student veterans on campus, a number that is expected to balloon again in a year or two when more transfer from other schools.

“If that’s the reputation, that’s all it is — a reputation,” says Gerald Kapinos x’10, an Iraq veteran who will graduate in December with a history degree.

The environment at the UW for returning soldiers is fundamentally different from the one that greeted Vietnam veterans. Even before they set foot on campus, they hear from John Bechtol, assistant dean for veterans since 2008, who works to stay connected to student veterans from the time they apply — sometimes driving long distances to meet with them — to the time they graduate.

Forty years after the deadly bombing of Sterling Hall, violent protests exist only in memory. Protest continues, but it is peaceful. Faculty have partnered with the Veterans Museum for a popular series of lectures on the history of foreign policy and the military. And veterans are welcomed into university classrooms, both in person and online, adding a new dimension to the educational experience for students with little to no knowledge of the military.

In 2008, the UW’s Vets for Vets organization — first founded in 1972 — was one of a dozen groups that created Student Veterans of America, a coalition that now has more than 250 chapter members on college campuses across the United States. The UW even made the first-ever list of military-friendly schools, created by G.I. Jobs, a magazine produced by veterans that honors the top schools for recruitment, retention, and services for veteran students.

What is making these connections possible where they once seemed anything but? It’s the political environment we’re in, as a university and as a nation, says Jeremi Suri, a UW history professor who helped found the museum lecture series and is engaged in other outreach efforts to veterans.

“This effort to struggle through these pro- and anti-war positions has actually created a wonderfully fruitful environment for discussion and for open engagement around these issues,” Suri says. “So I tell people, when they ask me, ‘Is Madison still an anti-war campus?’ I say, ‘No, but it’s also not a pro-war campus.’ … We’re a community trying to figure out new ways of understanding these issues.”

This shift is occurring as some Vietnam veterans are seeing an awakening of interest in their own wartime experiences, and as soldiers who are returning home from Iraq and Afghanistan are starting the next chapter of their lives as college students.

Their stories tell the UW’s story.

Al Whitaker ’63, JD’73

“I crossed the line.”

Al Whitaker did what any Badger would do upon returning to the UW-Madison campus for the first time in years: he headed to the Memorial Union. Fresh out of active duty in the air force after seven years — including a year in Thailand as an avionics maintenance officer for F-105 bombers flying missions into North Vietnam — the one-time UW football player was ready to begin the next chapter of his life and attend graduate school. There was one hitch: the bags containing his civilian clothes got lost in transit. So Whitaker, the son of a Tuskegee Airman whose earliest memories are of soldiers and planes, was still wearing his uniform on that day in December 1969 in the Union, when he heard someone call him “baby killer.”

“Of course, when you first come back, that’s where you go, to the Union, because [it has] so many memories,” Whitaker says. “Never had I experienced anything like that in the years prior.”

ROTC participation was still mandatory during Whitaker’s first two years of college. “The military was viewed probably like any other organization,” he says. “Once or twice a week, we had to put our uniforms on to go to our classes, and we fit in like all the other students.”

Whitaker enlisted in the air force after earning a degree in history, leaving a campus where the best Homecoming float was considered a big deal. He returned to a campus where ongoing anti-war protests meant anger, tear gas in the air, and troops with fixed bayonets on Library Mall.

“I give the students credit for having the courage to act on their convictions. They were ahead of me in their thinking in questioning the wisdom and the morality of the war. I freely acknowledge that,” he says.

But Whitaker felt a gulf of separation between his purpose for being on campus and that of the student protesters. His father had always stressed the importance of getting an education, he recalls.

Whitaker has strong memories of his seven years in the air force — and his return to campus in 1969. Courtesy of Al Whitaker

“I felt I could not afford the luxury of missing classes when they were talking about boycotting classes. ‘Don’t cross the line,’ right? ‘Boycott your classes.’ Well, as a black guy in America at that time and to some extent even today — no. You cannot afford to be governed by those high ideals that as a practical matter won’t get you a job,” he says. “And so I can remember thinking, ‘No, I’m not part of this.’ I did not go out to demonstrate. I went to my classes. I crossed the line.”Today, Whitaker is an attorney for Wisconsin Aviation, where air force memorabilia and a poster of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial with the words, “Never Forget,” cover his office walls. “These are people you know, and you work with, and befriend and drink with, and joke with and smile, and love. One day they were here and the next day, they were gone,” he says.

“Even now, [after] all these years … I have an extremely difficult time if I think about that too much.”

Dan Schuette ’71

“Nobody showed up.”

As an undergrad, Dan Schuette scheduled his drill class first thing Friday morning, giving him enough time to return to his apartment and change from his Army ROTC uniform into his “civvies” before classes began.

“If you were walking around campus all day with a [uniform], you were going to get harassed,” Schuette says. “At that time, I was young, dumb, and invincible, so I’d probably take the guy on. I’d probably take three guys on.”

After dropping out for a semester, changing majors, and partying too much, he had twenty credits left before he could graduate. “I wouldn’t give up the experience for anything,” he says, laughing. He left campus in spring 1967 to enter infantry officer training before spending a year in Vietnam as a helicopter pilot and platoon leader.

“I grew up a lot. I had a lot of responsibility,” he says. “You never know how you’re going to react until the bullets start flying. So when they started flying, I reacted pretty well. It gave me a lot of confidence.”

There were still protests when Schuette returned to finish his economics degree three years later.

“We come back. We have to kind of walk in the shadows,” he recalls. “Today, there’s parades or units coming back, and the governor shows up or the senator shows up, and all the local politicians and bigwigs show up. Back then — trust me — nobody showed up.”

Back home, married with a young son and focused on his studies, what Schuette saw on campus was, he says, “a bunch of hippies who didn’t shave and shower very often who had nothing better to do than protest the war. Now, I respect their viewpoint more. I look at the whole war in Vietnam saying, ‘Was it justified? Did it make sense?’ ”

Schuette, who has reflected on Vietnam more during the last few years since retiring from his job as a sales manager, still believes that the protestors — while questioning the war — should have supported the troops. He has attended a reunion of the Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association and lectures at the Veterans Museum, and he audited a class at the UW in fall 2008. Upon scanning the course list, he thought to himself, “ ‘Vietnam Wars’ — that’s the one.” He quickly realized that while he was in Vietnam in 1969, the professor for the class had been protesting the war in Washington, D.C.

“I grew up a lot,” says Schuette, recalling his days as a helicopter pilot in Vietnam. Courtesy of Dan Schuette

He says that while he knew a lot about his year in Vietnam, the class taught him “the rest of the stuff” — what led up to the war and what has happened since. With a discussion group of two dozen students, he shared what it was like being on campus during wartime. He read a poem about the anti-war protesters that he wrote prior to leaving for Vietnam and posted in the window of the Kollege Klub, where he was a part-time bartender.

“Now here we are: two wars that aren’t too popular,” he says. “Why isn’t it a big uprising now? … There was a draft back then. You could get sent over there against your free will. So it was more personal back then. [If] you were number 87 [in the draft] — your butt was going over there.”

Jim Kurtz ’62, LLB’65

“It really hit me hard.”

The day Jim Kurtz graduated from law school, there was a letter in his mailbox from the army, ordering him to report for active duty in September 1965.

“Lyndon Johnson was watching me carefully,” he jokes.

ROTC was mandatory when Kurtz entered the university in 1958, and he stayed in ROTC through law school, even though he had the option of dropping out after two years. “Virtually everybody was getting drafted,” he says.

For the Madison native, coming home in 1967 and being greeted with apathy and disdain was, he says, “a lot worse than being in Vietnam.”

As an attorney for the Department of Natural Resources, Kurtz was assigned to work with conservation wardens detailed to help protect state property during protest marches up and down State Street, either near university buildings or by the state capitol. He was there to advise when authorities could make arrests and when they would be trampling on the free speech rights of protesters. Although Kurtz firmly believed in the students’ right to protest, the realities of his job became incredibly difficult when things suddenly got personal.

“These people were yelling … ‘How can you be defending these baby killers? They’re murderers!’ ” Kurtz remembers. “And it occurred to me they were talking about me. They had no way of knowing who I was or anything like that, but it really hit me hard, and that put me in a shell for a long, long, long time.”

Since retiring in 2002, Kurtz has interviewed upwards of one hundred and twenty-five fellow Vietnam veterans for an oral history project for the Wisconsin Veterans Museum, and he serves as commander of the Middleton, Wisconsin, post of the Veterans of Foreign Wars. Through his work with the museum, he met John Cooper, a UW emeritus history professor, who asked Kurtz to speak to one of his classes about his experiences. Cooper also encouraged him to audit Jeremi Suri’s course on the history of U.S. foreign policy.

“I’ve audited a bunch of history courses,” Kurtz says. “Both Suri and Cooper make a conscious effort to get veterans or serving military to come to their classes, and they are treated just the same as anybody else. Actually, [they are treated] with some curiosity — ‘Wow, they’re doing something that’s kind of special.’ ”

While he and other members of his VFW post want to ensure that veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan have a better homecoming then they did, Kurtz struggles somewhat with the idea that people support those soldiers even if they don’t believe in their mission.

“That’s the thing that I’ve asked some of [Suri’s] classes … and these smart people can’t answer it either,” Kurtz says. “If people are saying the cause isn’t any good but we appreciate what you’re doing — I don’t know how you put those two together.”

Wyl Schuth x’11

“It’s coming full circle now.”

After four years in the U.S. Marine Corps, including eight months in Iraq, Wyl Schuth was looking for a school with a good academic reputation close to his hometown of Winona, Minnesota. The UW’s past didn’t enter into his decision, but his choice had his parents scratching their heads.

“I knew that from an academic standpoint, this was where I wanted to be. And the reputation — particularly among people my parents’ age — of this school comes from the ’60s, and They Marched into Sunlight, and that kind of thing,” he says. “Somebody coming from active-duty military to Madison didn’t quite jibe with them.”

Schuth, twenty-eight, is working toward a history degree and hopes to pursue graduate studies in military history at the UW, a setting he sees as an interesting case study for his academic interests. He notes that inside the Wisconsin Historical Society on campus, there is an old photograph of an enormous banner hanging in the building’s reading room with 1,750 stars — one for every UW student who was serving in World War I. It’s a stark contrast to how Vietnam veterans were treated on campus.

“That radical shift from being very supportive to it being a very polarizing environment for military members … I think in some ways, it’s coming full circle now,” he says. “So I think it’s a really interesting microcosm of the way that the entire country has thought about these things.”

Schuth is a teaching assistant for a course on the role of media, including music, during the Vietnam War. When he previously took the course, taught by Craig Werner, he told his classmates that no one in Iraq listened to Armed Forces Radio; instead, everyone had their own soundtrack to the war. “Everyone was probably listening to Otis Redding in Vietnam, or everyone was listening to [Creedance Clearwater Revival] or something like that,” he says. “But in Iraq: iPods.”

Schuth, who served in Iraq, believes the campus — and its shifting attitudes about war — is a microcosm of the entire country. Courtesy of Wyl Schuth

John Hall, a UW history professor, relies on student veterans in his classes to provide such personal perspectives, including the relationships soldiers have with the societies they serve, the experience and stresses of being involved in a war, and the motivations for joining and getting out of the military.

“Some aspects of a soldier or marine or airman or sailor’s experience do seem to be fairly timeless, even if we’re talking about the Civil War, the First World War,” Hall says. “These veterans have a perspective on homecoming and the importance of getting letters from loved ones and those sorts of things that I’m able to incorporate all the time.”

Gerald Kapinos x’10

“We have this tremendous well of untapped material.”

Gerald Kapinos, twenty-nine, joined the air force after 9/11 and served as an MP in Iraq in 2006 and 2007. He came to the UW in fall 2008, after transferring from UW-Whitewater, and hopes to find work in law enforcement after he graduates in December.

Studying military history has helped Kapinos answer questions about the Iraq war and move on to the next phase of his life, he says. “I’m just trying to figure out: what is the part that I played? What is the role that I had? What are the implications? Was it the right thing to do, was it not?”

If the fact that Kapinos is a veteran comes up in class, the typical response is curiosity, not hostility, he says. “I thought I would be a resource, and in talking to other student vets that plan on coming here, they feel the same way,” he says. “We have this tremendous well of untapped material that we can bring back and contribute to the campus that I think is invaluable to the rest of our fellow students.”

Kapinos is also president of the UW’s Vets for Vets, a campus group with a primary mission to help student veterans overcome some of the barriers — including age and experience — they face in connecting with fellow students, and to help them graduate.

“When I came onto campus right out of the military … I’m sitting next to eighteen-year-old kids who, for all intents and purposes, don’t know anything,” he says. “Their biggest life experience is moving out of home and living in a dorm. When I was going for my first combat tour, they were in junior high.”

Kapinos, who served as an MP in Iraq, welcomes the curiosity from his classmates when they learn that he’s a veteran. Courtesy of Gerald Kapinos

Kapinos and Wyl Schuth have found some kinship on campus with the 396th Chairborne Badgers, a small group they formed with classmates from John Hall’s History 396 course. The group also includes a student who is planning to become a marine officer, another who attended West Point, one who is the wife of a former army officer, and others who have an interest in military issues. The students meet regularly for dinner or cookouts, talking not only about the material Hall has covered in class, but also their own experiences. The camaraderie of the 396th, along with the university’s strong ties with the veterans museum and the faculty who are engaged in military issues, add up to a campus experience Schuth didn’t count on.

“It surprises me, because I hadn’t expected to find it here. I hadn’t expected any adversity, but I hadn’t expected, maybe, anything at all,” Schuth says. “I just thought maybe, oh, I’ll come here, I’ll go to school, I’ll just kind of be a ghost here on campus, and go to class and come home. It’s been nice to find that it doesn’t have to be that way.”

Professor John Hall: An expert in military history welcomes the chance to reach out to veterans.

When John Hall was growing up in rural southeastern Wisconsin, Madison was regarded as the home of the Badgers and the local TV stations his family tuned in on their “very wonky rabbit-ear antennas.”

He says it wasn’t until he left the state for a career as an army officer and began studying military history that he realized “Madison had a reputation of being a particularly liberal, even radical bastion” in the Midwest.

But as the 1994 West Point graduate and son of a Vietnam veteran began to pursue a faculty position as professor of American military history at the UW, Hall found the campus didn’t live up to that image, “but the reputation lived on,” he says.

Hall was hired in 2009. Three years earlier, an online article from the National Review had suggested that the UW hadn’t filled the professorship — endowed by best-selling author Stephen Ambrose ’57, PhD’63 — because the university didn’t actually want a military historian on its faculty.

“This sort of fit the popular mold of depicting Madison,” Hall says.

Hall’s job interview process was a bit different from those of typical faculty. Representatives of local veterans organizations, the Wisconsin Veterans Museum, and the Wisconsin Historical Society got to weigh in on the search. Jeremi Suri, a UW history professor who led the process, says it was critical that “whoever we hired fit the mold of being a great scholar, but also would engage people who had not been engaged for a long time. … We wanted to attract someone who was a top-notch researcher, but someone like John who also liked making those connections.”

That gives Hall a packed schedule, which he welcomes.

“I was under no illusions,” he says. “When I applied for the job, I understood and was excited about the fact that it entailed a significant amount of outreach within the community with these organizations … and among the community’s veterans.”

Part of that effort is welcoming veterans into the classroom. Richard Berry, who flew army helicopters in Vietnam, has so far audited more than a dozen courses at UW-Madison, including one of Hall’s military history classes, to enhance his work as a docent at the Wisconsin Veterans Museum.

“I would say that, to a person, the students in the class know more about the antecedents to the Vietnam War than I did when I enlisted,” says Berry.

That runs counter to the perception that Vietnam veterans are reluctant to talk. “If you give them an opportunity to speak about their [wartime] experience, a great many of them are more than willing to share that experience,” Hall says.

Professor Jeremi Suri: Bringing veterans into the classroom opens eyes and dispels stereotypes.

When Jeremi Suri and Jim Kurtz get together, there’s bound to be a disagreement or two. Or three.

The UW history professor and the Vietnam veteran don’t exactly see the world the same way, yet the two formed a dynamic friendship after Kurtz audited Suri’s class.

“Every book I write, [Kurtz] reads chapters and tears them apart,” Suri says. “It is a huge joy for me to sit down with him and have him look at something I’ve shown to three or four academics — but get his thoughts.”

Several years ago, Kurtz suggested that Suri get involved with the Wisconsin Veterans Museum. A series of conversations the pair had with then-museum director Richard Zeitlin MA’69, PhD’73 led to a popular lecture series featuring experts on military history and foreign policy, including UW faculty. The lecture series at the museum, which launched in 2003 with support from the UW’s Center for World Affairs and the Global Economy, began the university’s effort to create educational experiences that bring veterans and military officers together with students and researchers.

“For me, it’s really fun,” Suri says. “Creating an environment that’s open to veterans in a way that it wasn’t before exposes us to different ideas, exposes us to interesting people, and exposes us as scholars and students to being surprised.”

In 2009, Suri launched an online course called U.S. Grand Strategy, designed to appeal to active-service members of the military. Nearly two dozen of the 130 students enrolled were officers in the armed forces, including some in Iraq and Afghanistan. As a follow-up, about ten military officers who took part in the course came to campus for a weekend to meet with twenty undergraduate students in Suri’s seminar on strategy and foreign policy. The students and officers split into four teams, and were given an assignment: prepare a briefing for the president on what to do after 9/11 and present it to a panel.

For students and soldiers, these kinds of interactions are invaluable, Suri says.

“They recognize that all military officers are not these pro-violent guys, and the military officers recognize that not all students are anti-military,” Suri says. “I think that’s far more effective than just a scholar chastising people for having stereotypes. The best way is to actually display to them the complexity that’s being lost.”

Suri and other faculty, including political science Professor Jon Pevehouse, taught a summer series of graduate-level online strategic studies courses through which military members could earn UW credit and a potential avenue to further study on campus.

“My department, other departments have been really incredibly open to admitting veterans to graduate programs in a way that probably would not have been true years ago,” Suri says.

Jenny Price ’96 is senior writer for On Wisconsin.

Published in the Fall 2010 issue

Comments

Glenn Hojem September 8, 2010

Sharing people’s experiences during war time is important for our youth. I retired from teaching Respiratory Therapy for 27 years at MATC in Dec. ’04. I served 2 tours of duty in Viet Nam in the late 60’s while in the Navy. We had 500 sailors on my ship and 2,000 Marines; we did amphibious landing on the beaches with them and got their wounded back aboard our ship.

What I saw and experienced will never be forgotten, that is partly why I work part time at the Madison V.A Hospital where most of the patients a from the Viet Nam era.

Gail Bailey September 9, 2010

As the mother of a son who is now a Staff Sgt. in the Army, I would like to thank all you veterans for your bravery, your courage, your service. I always respected veterans, but I have a deeper appreciation and insight now that my son is serving. He served in Afghanistan in 2005 and is now in Iraq. The courage it takes to be in harm’s way is such a selfless act and reading these stories made me tear up as well. God bless our veterans. My father, Jerry Gauthier, served in the Navy for four years also, and I admire the courage, the bravery, the selflessness so much. Thank you for all you do and all you have done! Gail Bailey

Heidi Andrew September 10, 2010

As a UW-Madison student and veteran of both OIF and OEF, I have to say that I have seen a lot of the anti-war side of UW-Madison. I was recently called a baby killer and I have found my car vandolized after parking it while wearing my uniform. I still have yet to see the changed UW-Madison.

Anonymous September 14, 2010

I think it is important to hear veterans stories and especially important to show them respect. I visited the Veterans Museum two weeks ago and reading the stories and plaques left me with a lump in my throat. I can’t begin to imagine the things that our troops see overseas and they deserve our support when they return home.