Two days after Hillary Clinton clinched the Democratic nomination, President Obama endorsed her candidacy for president. Her opponent did what any candidate today would do: he took to Twitter to share his thoughts.

“Obama just endorsed Crooked Hillary,” GOP nominee Donald Trump tweeted. “He wants four more years of Obama — but nobody else does!”

Unflattering adjectives had become Trump’s trademark dig, which his Twitter followers relished. With “Low-Energy Jeb,” “Little Marco,” and “Lyin’ Ted” out of the race, his attention was squarely focused on his general-election opponent.

Election 2016

Join UW experts for a web chat on September 20,m 7 to 8 p.m., at go.wisc.edu/onwischat. Submit questions via Twitter using #OnWisChat.

Then came a deadpan reply from Clinton, quoting Trump’s original tweet: “Delete your account.”

Thousands shared her response within minutes. By the end of the day, it garnered 330,000 retweets and became her most popular tweet of the campaign.

Trump fired back a few hours later: “How long did it take your staff of 823 people to think that up — and where are your 33,000 emails that you deleted?” The scathing reply gained thousands of retweets (though 200,000 less than Clinton’s reply).

In the end, it was a fairly successful day for them both.

Every so often, a witty comeback, candid photo, or visionary quote a politician shares on social media inexplicably takes hold, sparking a chain of positive reactions. But an online misstep can end a career just as swiftly, while blandness can fail to start one. Because 65 percent of voting-age Americans use social media, politicians have no choice but to play this delicate — and risky — game.

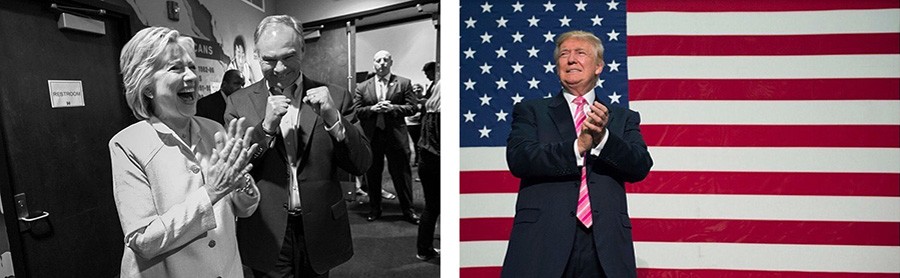

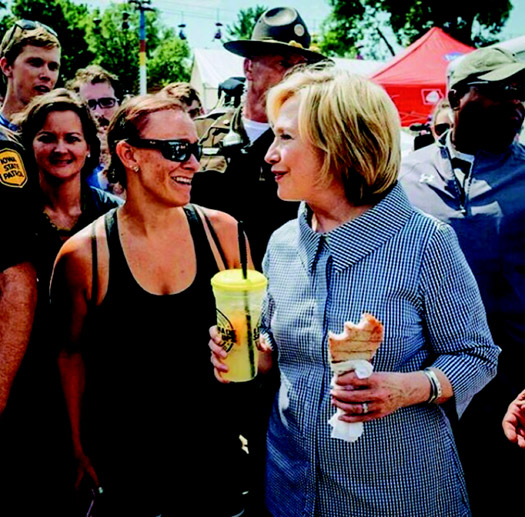

Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump use Instagram to share photos (below) of their families, including new grandchildren, and behind-the-scenes moments from the campaign trail.

22 people had to approve every one of Mitt Romney’s tweets before it could be posted during the 2012 presidential campaign.

Real-time spin

Not only are huge numbers of people using social media, but they increasingly rely on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter to get informed. Nearly 40 percent of baby boomers and more than 60 percent of millennials say Facebook is their primary source for political news. Many campaigns have realized that Facebook is where they can reach the largest number of people in a streamlined way, says Katie Harbath ’03, who was e-campaign director for Rudy Giuliani’s 2008 presidential bid.

Harbath, who recalls how Giuliani’s small digital team was separate from the rest of the campaign, now works as a global politics and government outreach manager at Facebook, where politicians consult her about how to use the site to their advantage. She notes that today’s presidential candidates employ armies of digital and social media specialists. “The campaigns that do it best have digital and social media integrated into every part of their campaign,” she says.

Social media gives candidates a megaphone to address large numbers of people, instantly respond to criticism, or broadcast their reactions to an opponent’s statement. It’s an ideal tool for candidates to increase name recognition and showcase their values and personality.

“It’s great for hyping up the crowd, and it’s great for momentum,” says Maura Tracy x’10, who studied political science at UW–Madison before leaving to work on state and congressional races in the Midwest.

Because social media is a constant presence, accessible at all hours of the day, it has also changed how candidates campaign. And it has altered the way we watch debates, says Dhavan Shah ’89, director of the UW’s Mass Communication Research Center.

“The spin room isn’t something that happens after debates anymore. It’s something that happens in real-time,” he says.

This is because people are “second-screening” — watching the debates while simultaneously following and posting reactions on social media. During the first Democratic presidential debate, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders gained more than 30,000 followers on Twitter. The jump became a news story in itself. More than applause lines or witty turns of phrase, social media users most frequently react to body language and facial expressions, and Shah says this insight has helped politicians’ handlers give them instant feedback on their quirks.

Depending on how many followers candidates accumulate on social media platforms, they have an audience of anywhere from several thousand to millions of people at once. “It’s more people than you can reach if you are only speaking to people in a room,” says Lauren Peterson ’10, director of content and creative for Clinton’s campaign.

Clinton’s team starts each morning by discussing social media, emails, blog posts, and videos that will roll out each day to make sure their messages will be coordinated. On the day that Clinton announced her campus sexual assault plan, the social media team coordinated tweets and Facebook posts with her visit to a college campus in Iowa while the communications team set up an interview with Refinery29, an online media outlet focused on women. “We’re all kind of telling the same story, just to a slightly different group of people,” Peterson says.

Because everyone — candidates, news outlets, celebrities, and companies — churns out constant content, it becomes even more important to repeat messages and to post them across several platforms. Quantity is one way to garner a following on social media, but quality matters, too. Most presidential candidates (Trump appears to be a notable exception) have teams who carefully vet each piece of content before sending it out to the masses.

“Most staffers take a lot of pride in their candidates and don’t want to do anything that would embarrass them,” Tracy says. Campaigns sometimes show staffers examples of disastrous tweets to encourage them to think carefully about posts and what would happen if those tweets ended up on CNN. They also ensure staffers know how to operate each social media platform.

And they make certain a candidate’s tweets or Facebook status updates get a second, third, fourth, and fifth look before they are posted. “Not just for wording, but for things that could be taken out of context,” Peterson says. “Or there might be a word with ambiguous meaning, and we don’t want to leave anything up to chance.”

And if something gets overlooked? Too late, she says. “You hear about it right away, within seconds.”

Sometimes the blame rests squarely on the politician’s shoulders, like when twitchy fingers result in an impulsive post. After last year’s terrorist attacks on Paris, Minnesota state House candidate Dan Kimmel tweeted that ISIS was “made up of people doing what they think is best for their community.” The outraged response was immediate, and his withdrawal from the campaign was only hours behind.

Clearly, the goal is control. Twitter offers a popular 136-page handbook that teaches politicians to get the most out of their tweets. But it’s still a constant balance between being instantaneous — such as live-tweeting during a debate to pounce on an opponent’s mistake — and cautious. Former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney’s failed presidential campaign was criticized for having a tweet-review bottleneck: up to 22 people had to approve every one of his tweets before it could be posted.

“That is not sustainable,” Peterson says.

Authenticity

To change people’s opinions, politicians need to foster a good relationship with their audience, which usually necessitates a long-term social media strategy built up over months and years. Above all, it must ring true. But authenticity can be tricky for politicians used to delivering pat answers and carefully constructed speeches.

“People have such a keenly developed sense of what’s authentic, what’s actually written by someone versus what’s just a generic campaign talking point,” Tracy says.

Columnists and pundits trace Trump’s and Sanders’s popularity to the way they present themselves as unfiltered. It’s easy to believe that Trump writes his own tweets, and it’s obvious that he’s not holding anything back. The often-disheveled Sanders is a sharp contrast to Clinton, whose Instagram account includes selfies with high-profile celebrities. Authenticity is thought to be especially important to millennials, and this may be why Sanders consistently did better with voters under 30 in primaries and caucuses.

Over the course of political history, young people have “always been incredibly astute at ferreting out a lack of authenticity, and ruthless in punishing candidates for it,” says Michael Xenos, a UW professor and chair of the communication science department.

It is hard to define exactly what, or who, seems authentic, Xenos says. It often comes down to this: “We know it when we see it.” That’s a nebulous ideal that can be difficult for candidates to wrangle with, and it sets them up for mistakes and missteps.

Nevertheless, even the most scripted candidates use social media to make direct appeals to voters. Sometimes this can be as simple as posting direct-to-camera video, live streaming, and any behind-the-scenes footage to Snapchat (see sidebar) to help voters better understand a candidate.

It is especially important for candidates to have a well-tailored strategy that plays up their strengths and plays down their perceived weaknesses. What works for one candidate does not hold true for another, Xenos says.

“Many people have said and will continue to say that [President Obama] couldn’t have done what he did without social media,” he says. “If you were to take that social media operation and just slap it on another candidate, it probably wouldn’t have the same effect.”

Meme storms

Social media is part of a good offense, but campaigns also have to be ready to use it to defend a candidate when he or she is hit with criticism or mockery. During 2012’s second presidential debate, Romney alluded to the “binders full of women” provided to him during his search for more female cabinet members. The odd phrase was memorable, and ridicule ran rampant online.

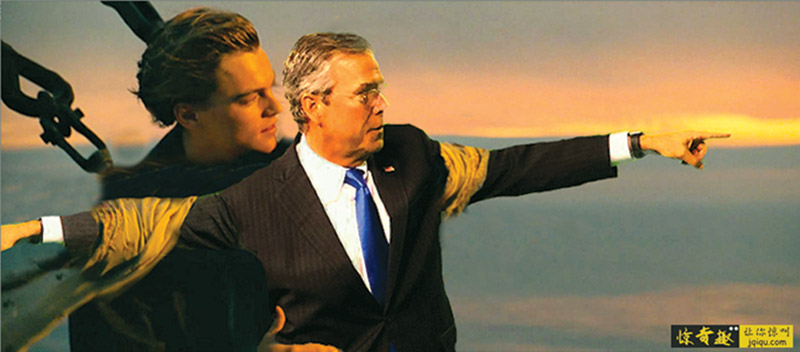

Before he ended his campaign in February, Jeb Bush was the subject of a green screen meme storm. Bush tweeted a picture of himself pointing in front of a green screen with the caption, “Taking lessons on how to work the green screen and give a weather forecast.” The website Reddit set the stage by tweeting, “This is going to be a memorable Photoshop battle.” Internet users gleefully put Bush in the movie Pulp Fiction and on stage at a Kanye West concert, made a laser shoot out of his finger, and placed him side by side with Darth Vader.

Harbath believes that when faced with this kind of social media response, the smartest thing a politician can do is “lean into the punch.”

It worked for Republican Senator Marco Rubio after he gave a sweaty and uncomfortable response to the State of the Union address in 2013. He faced mockery for reaching awkwardly off camera to grab a bottle of water and guzzling its contents on live television. Rubio decided to be in on the joke. He made fun of himself on Twitter and his campaign later sold water bottles printed with his name.

“He turned something that could have been a potential negative story into a positive story because they were so clever in terms of how they handled it,” Harbath says.

Rubio employed a similar strategy in June 2015 after the New York Times wrote an article detailing the traffic infractions he and his wife had accumulated over the years. Twitter users comically employed the hashtag #rubiocrimespree, accusing the senator of other “crimes,” such as jumping into a pool directly after eating. Months later, his presidential campaign produced a video accusing him of heinous crimes like double-dipping his chips after theWashington Post revealed that an 18-year-old Rubio had been arrested for drinking beer in a public park after it had closed. The campaign turned both incidents into opportunities to fundraise. Alex Conant ’02, MPA’03, who declined to be interviewed, was the communications director for Rubio’s presidential campaign.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s opponents tried to use his seemingly perfect hair to suggest he was an unprepared pretty boy, something that might have concerned a candidate who wanted to be viewed as a serious statesman. But Trudeau’s campaign knew his hair was a trending topic on Facebook, and tweeted a promotional video with the caption, “While we’re all on the topic of hair, a reminder of what really matters.” Later, his political party released another video called “Your Guide to Canadian Political Hair,” embracing rather than denying the Internet’s obsession.

Candidates often have much more serious issues to contend with — poor debate performances, inconsistent voting records, miscalculated attempts to connect with voters, or, once in a while, a major scandal. “There’s not something you can magically put up on Facebook the next day that’s going to all of a sudden change people’s opinions about that candidate,” Harbath says.

In 2011, married New York congressman Anthony Weiner was accused of using Twitter’s private messaging feature to share sexually explicit photographs of himself with multiple women. Weiner tried, at first, to claim someone had hacked his phone, but he eventually owned up, apologized, resigned from Congress, and swore off sexting. Two years later, more evidence from those indiscretions surfaced during his campaign for mayor of New York.

Tracy, the UW alumna who is a veteran of several campaigns, was a senior staffer on Weiner’s mayoral campaign at the time. The former congressman had launched his campaign by owning up to his previous transgressions and promising a fresh start. “He really thought about the best way to handle that, because it’s a very public part of him now, no pun intended,” she says.

Once Weiner apologized yet again, Tracy says he followed “classic communication 101” by trying to change the conversation and resumed unveiling his ideas for the city of New York, but by that point, voters had stopped listening.

Former Florida Governor Jeb Bush got caught in a “meme storm” when Internet users had some fun with a photo of the presidential candidate in front of a TV studio green screen.

- FACEBOOK

Politicians use Facebook the same way everyone does: to post status updates, share news articles, talk politics (naturally), or show off cute pictures with their grandkids. They also use it to fundraise and promote their vision for the country. By “liking” a politician’s page, supporters can guarantee his or her updates show up in their newsfeed. - INSTAGRAM

Unlike Facebook, which welcomes words and media alike, Instagram is a photos-first social media platform. Best known for faux-artsy, lifestyle snaps — think photos of someone’s brunch entrée — Instagram also humanizes candidates, creating an illusion of intimacy with their followers. Hillary Clinton’s account posted a candid shot of her holding a half-eaten pork chop and a jumbo lemonade with the caption, “Doing the #IowaStateFair the right way.” - SNAPCHAT

Snapchat users share photos or short videos, often with added doodles. What differentiates the platform from other forms of social media is users’ content self-destructs after it’s viewed. “Snaps” are meant to be enjoyed in the moment — and probably are not important enough to save. Candidates often share footage from rallies to flaunt their crowds. - TWITTER

Twitter users post brief, 140-character dispatches — with or without images and links — called “tweets.” Campaigns most frequently use the platform to birth hashtags (see: #FeelTheBern), live-tweet debates and media appearances, publicly spar (see: Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren and Donald Trump), and, every once in a while, clarify policy positions.

Retail politics

Being a trending topic on social media does not necessarily translate to success at the polls. A candidate who has a lot of interaction with his or her supporters will likely enjoy a boost in popular opinion, but that doesn’t always translate to electoral success.

“Barring really bad decisions, both candidates in competitive races tend to do very similar things in social media, and one of those candidates is going to win and one is going to lose,” says Xenos, the UW communication science researcher.

While social media is a good way for politicians to spread information about themselves and their opponents, the most successful campaigns use it alongside more old-fashioned methods, which can better reach key groups of voters over the age of 65.

“The door-knocking, and — I know people hate it — the phone calls, are the way to reach the people that you need to get to vote,” says Tracy. And when it comes to fundraising, using targeted email campaigns, and not social media, is the most effective way to bring in donations, at least for local and state-level races.

Behaviors might change as social media users age and algorithms advance to better target potential donors, but Tracy says retail politics will never be rendered obsolete. “A visit is more memorable than a tweet that disappears in a few minutes,” she says.

Still, a strong social media presence is a requirement for high-profile political campaigns. Candidates hope to wield it in their favor for donations, votes, and the elusive “likability factor.” They gamble some control in hopes of a larger payoff.

Xenos says making that bet is especially important for reaching a key demographic: people who are not particularly interested in politics or elections and instead use Facebook to look for recipes and cute cat videos. Political information shared on social media by politically active people will almost always be seen by their less politically active friends.

“They get that little piece of campaign information that they weren’t looking for,” Xenos says. “They’re not paying attention to politics — most people have better things to do — but social media is a way for it to get pushed in front of them.”

So, would having superior digital presence ever win an election?

Tracy doesn’t think so, unless two candidates were in a dead tie. “Everything equal, and one candidate has a better Twitter?” she says. “Maybe.”

Gretchen Christensen, Cara Lombardo, and Lisa Speckhard are graduate students in the UW School of Journalism and Mass Communication.

Published in the Fall 2016 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.