Estella Leopold ’48: Carrying on the Leopold Legacy

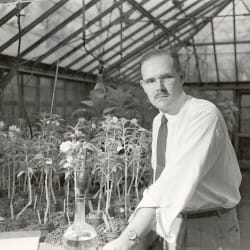

Estella Leopold’s passion for nature was spurred by her father, Aldo Leopold, one of the founders of the environmental movement. Photo: Don Burgess

“We can learn plenty from the past,” says Estella Leopold ’48.

She should know. As a paleobotanist, Leopold has spent more than fifty years combing through pollen fossils to reconstruct the history of climate change and plant evolution on our planet. Now a professor emerita at the University of Washington in Seattle, she has used her scientific expertise to lobby successfully for conservation efforts across the country.

In recognition of her contributions to environmental science and protection, the Japanese Expo ’90 Foundation last year awarded Leopold its $460,000 Cosmos International Prize. (Other recipients include ecologist Jared Diamond, naturalist George Schaller MS’57, PhD’62, and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins.) Not bad for someone who originally aspired to study bugs.

“I was quite young, and Father asked what I wanted to be,” the eighty-three-year-old botanist recalls. “I said, ‘A bugologist.’ And he said, ‘What?! Why is that?’ And I said, ‘Because everything else is taken.’ ”

A word of explanation is in order. Father was Aldo Leopold, a UW professor of game management and perhaps the most influential ecologist of the twentieth century. His land ethic, which holds that human beings are but one part of a larger community comprising all plants and animals, helped to spark the modern conservation movement. And everything seemed taken because her four older siblings had already gone into fields ranging from geology to hydrology. (Three of the Leopold siblings, including Estella, have been elected to the National Academy of Sciences.)

Father persuaded daughter to pursue botany instead, and Estella spent her weekends at the shack, an eighty-acre sand farm near Baraboo, Wisconsin, which now houses the Aldo Leopold Foundation, on whose board she sits. The shack became an ecological restoration project for the entire family — and the spur to the youngest Leopold’s lifelong passion for nature.

Early in her career, Leopold used ancient pollen fossils to prove that South Pacific atolls were formed on sinking volcanoes — a hypothesis first posited by Charles Darwin in 1839. Later research into plant fossils from Alaska, the Pacific Northwest, and the Rocky Mountains illustrated how the environment has responded to climate change over millions of years.

Her environmental activism has paid equally large dividends. Leopold played a central role in establishing both the six-thousand-acre Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument in Colorado and the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument in Washington. And she fought successfully to prevent the construction of hydroelectric dams that would have flooded parts of the Grand Canyon and helped to block the burial of high-level nuclear waste under Hanford, Washington.

Today, Leopold concentrates her efforts on promoting sustainable agriculture in Washington State, and while she’s gratified by the rise in public awareness of environmental issues, she’s deeply concerned about the lack of exposure many children now have to the environment itself. After all, she traces her own love of nature — and all that has flowed from it — to her childhood exploring the wilds of Wisconsin.

“And without loving nature,” she says, “who’s going to want to protect it?”

Published in the Summer 2011 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.