Quantum Leaps in Education

Artificial intelligence is here to stay. UW–Madison students are grappling with its promise and perils.

hen Annika Hallquist ’24, MSx’25 reflects on her undergrad years at UW–Madison, she does so in halves: before AI and after AI.

hen Annika Hallquist ’24, MSx’25 reflects on her undergrad years at UW–Madison, she does so in halves: before AI and after AI.

Hallquist was a sophomore in November 2022, when the release of ChatGPT abruptly ushered in a new era of generative artificial intelligence. Initially, the industrial engineering student dismissed the AI chatbot as a “cheat tool.” But the following semester, the professor of her machine-learning class encouraged students to embrace the technology as something of a teammate and tutor — a tool that can assist with tricky coding tasks and reduce complicated concepts into understandable terms.

“I’m jealous seeing freshmen and sophomores take the incredibly hard weed-out classes that I took, knowing that they have AI,” Hallquist says. “I’d have to wait in a long line during office hours to get a coding project done. Now they use AI to help them if they’re stuck.”

“You want to use AI as a tool, but you don’t want to use it as a crutch.”

Still, she recognizes the value of her college education before AI and fears what skills incoming students might lose with its ease of use.

“I got the best of both worlds, because I had a really strong foundation in my coding skills, in mathematics, in chemistry, in physics,” says Hallquist, who’s now pursuing a master’s degree with a focus on AI. “It’s critical to have that foundation for a future career. You want to use AI as a tool, but you don’t want to use it as a crutch.”

Fortunately for Hallquist and other UW students grappling with generative AI, their university has emerged as an early leader in the field.

In February 2024, the UW launched RISE-AI, the first of several focus areas for the Wisconsin Research, Innovation and Scholarly Excellence (RISE) Initiative. The effort takes an accelerated approach to hiring specialized faculty, investing in research infrastructure, and promoting cross-disciplinary collaboration. It aims to bring an additional 50 AI-focused faculty experts to campus over the next few years — and with them, a new catalog of cutting-edge courses to help students prepare for a brave new world.

No need to wait, though. There are already enough AI courses at UW–Madison to fill several semesters of credits. So this spring, I sat in on four futuristic classes that span the fields of engineering, law, philosophy, and educational policy. In all of them, I found instructors equipping students with both the technical skills and ethical frameworks to address the biggest questions of our time.

Not that the answers are yet clear.

EEK! AI!

Aaron Aguilar PhDx’27 has been teaching Educational Policy Studies 123 for just two semesters, but he’s already noticed a seismic shift among students when it comes to the use of AI in the classroom.

“The patience that students have for professors who are like, ‘Eek! AI!’ is really over,” he says. “They know that AI is here and we’re going to have to deal with it.”

In the introductory course — Education, Technology, and Society: AI, Big Data, and the Digital Divide — the students are tasked with crafting an AI policy on behalf of UW–Madison.

Aguilar tells the students that every decision they make around permitting or restricting use of AI reveals what they value or don’t value about education. Policy choices have far-reaching consequences, both practical and ethical.

“If you say, ‘I’m okay with AI proofreading papers,’ then you’re saying that you’re okay with students not developing or practicing proofreading skills,” he tells the class. “Or if you say that younger students need to develop the foundational skill before they use AI, now you have a conundrum. What’s the age? Where do you draw that line?”

Aguilar’s own policy for the course reflects the realities around the omnipresent tool. He allows students to use generative AI for writing assignments so long as they formally cite any language pulled from it and include a 200-word reflection on how they used it. But at the end of every class, he asks the students to close their laptops and handwrite a brief essay on a notecard.

“Instead of creating a policy that I can’t enforce,” Aguilar says, “I changed how I teach the class so I can get a constant perspective on their thinking process without guessing whether they used AI.”

AI is far from the first technology to disrupt education. But it’s a big leap from calculators to OpenAI’s deep research, which is so powerful it can produce a passable dissertation in a few days. At what point does assistance from AI encroach on true authorship?

In class, the students search for consensus around permissible uses of AI in essay writing. Yes for checking grammar and punctuation. Maybe for brainstorming and organization. No for original writing. Many argue that AI shouldn’t replace our own creativity, critical thinking, and chances to learn from mistakes, but they struggle to clearly delineate those processes in the context of policy-making.

One group writes on the board: “We value the process of learning, human error being essential to academic growth.”

The exercise informs their big group project: the university’s AI policy. Having grappled with all the complexities, most groups opt against a campuswide policy. Instead, they encourage instructors to define what they want their students to get out of a particular class and assess how the use of AI can align with those goals.

“I was smiling a lot as I was reading their papers, because they were making conscious decisions,” Aguilar says. “They’re now beyond cheating is bad or don’t use AI to cheat. They’re more precise about where they think AI should play a role and why.”

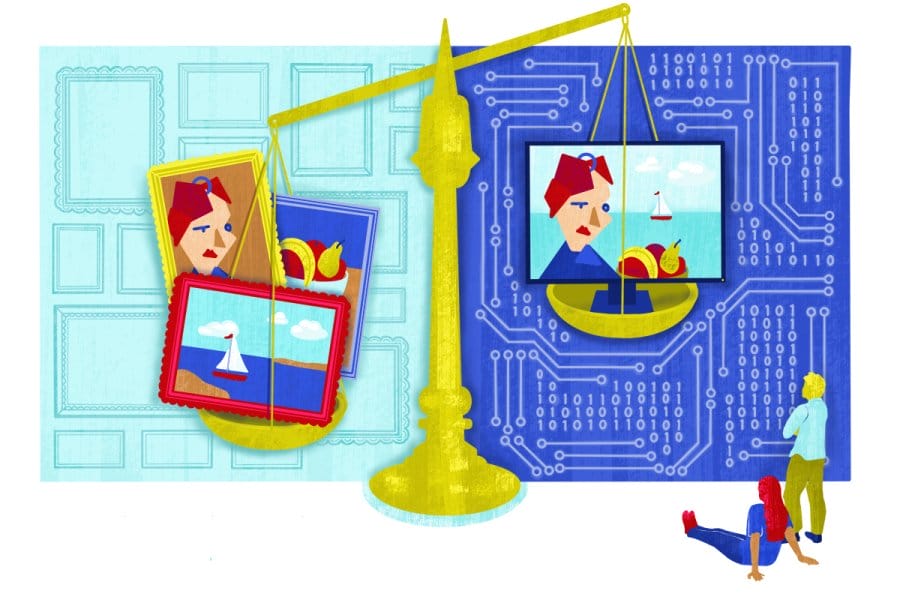

ART VERSUS AI

Questions around AI and authorship extend beyond the classroom to the courtroom. In the AI & the Law seminar, UW students tackle emerging legal questions in such areas as copyright, data privacy, and liability.

Professor BJ Ard is an expert in the intersection of law and technology, and his latest paper notes that generative AI “defies the assumptions behind existing legal frameworks.” This is due to the technology’s multifaceted training and creation process. A generative AI model is trained on a large initial dataset of text, photos, or videos that informs its output of new materials. If I copy an artist’s work, it would be fairly clear how, why, and when I did it. If AI does it, those questions become incredibly complicated.

Do you blame the parties that curated the training data? The developers who trained the AI model? The end user who wrote the generative prompt and pressed the button?

Ard notes that the involvement of so many actors over time makes it difficult to identify the purpose of the copying, which can be decisive under some copyright tests.

Copyright registration is among the more straightforward legal questions around AI, and even then, it can be dizzying. The U.S. Copyright Office does not protect any machine-generated works unless the human author can claim substantial control over execution. AI artists are pushing the limits of that position.

Ard presents two case studies from author and AI artist Kris Kashtanova. The comic book Zarya of the Dawn received copyright protections for its human-written text and composition but not for its AI-generated images. Simple enough. But the artist’s Rose Enigma, an AI-generated artwork based on a hand-drawn sketch, resulted in this arcane decision: “Registration limited to unaltered human pictorial authorship that is clearly perceptible in the deposit and separable from the non-human expression that is excluded from the claim.”

Got it? (Good thing there’s law school.)

Throughout the seminar, Ard aims to demystify the technology behind AI. He gives students a baseline technical understanding of the decisions involved in training and designing generative AI software.

“Nothing about these problems is easy, but they’re also not totally unprecedented,” he says. “There’s no need to shy away from them because you’re not a computer scientist.”

After class, I ask Signe Janoska ’17, MIPA’19, JD’25, a law student who uses AI for work as a software engineer, what initially interested him in the Law 940 seminar.

“It’s an opportunity to wrap my head around the legal challenges governing AI under the guidance of somebody who understands that about as masterfully as you can, given its early stage of development,” he says. “It hasn’t given me all the answers, but it’s given me tools and perspectives that allow me to wrestle with the questions.”

ETHICAL EQUATIONS

Does AI have moral rights?

It’s a classic philosophical dilemma, and UW–Madison’s AI Ethics course explores it in depth. In an absolutist camp, students argue that humans are a distinctive species, with unique cognitive and emotional capacities, and therefore constitute a category of their own with exclusive rights. The gradualists argue that other animals — and perhaps one day, conscious AI — have relatively high capacities and deserve more consideration. But if you try to draw that line, how do you account for the limited capacities of some humans, such as newborns or comatose patients?

What makes Philosophy 941 unique is not these high-minded discussions; it’s the highly technical exercises that tend to follow. The new field of philosophy of AI addresses concepts such as algorithmic bias — errors in a computer system that create unfair outcomes for certain groups of users. Unraveling the causes requires both a philosophical and a mathematical approach.

“There are some hardcore math topics in this class,” says Professor Annette Zimmermann.

Issues around algorithmic bias hit close to home. Wisconsin’s supreme court wrestled with its implications in the 2016 case State v. Loomis, which challenged the government’s use of a risk-assessment software in criminal sentencing. The algorithm calculates the likelihood that an offender will commit another crime based on actuarial data. Proponents of the predictive AI tool argue that it mitigates potential human bias. Critics point to a ProPublica investigation that found that Black defendants are “almost twice as likely as whites to be labeled a higher risk but not actually reoffend.”

If AI is trained on flawed data, it can perpetuate the same biases. This is of particular concern to AI philosophers, since research shows that people tend to automatically trust the accuracy and objectivity of machine-generated data.

Earlier in the semester, Zimmermann spoke virtually at the AI Action Summit in Paris. With a new book, Democratizing AI, she’s emerging as a leading thinker on how governments and citizens engage with the technology.

“Decisions to deploy AI are currently made by a very small set of corporate actors, like OpenAI and Anthropic,” she says, noting that U.S. policy-makers of all stripes have shied away from AI oversight. “Ordinary citizens should be able to provide input on decisions that will affect them, either through direct participation or by elected representatives. It looks like neither is happening in this case.”

If politicians aren’t up for the challenges of AI, perhaps her students will be. The course has inspired Lydia Boyce ’25 to pursue a career in AI ethics after graduation — “to be part of the rising effort to establish an industry norm of more equitable and accessible AI,” she says.

Zimmermann’s main goal is to help her students avoid superficial stances on AI.

“Right now, public discourse oscillates between two extremes — AI hyperism, which wants deployment without guardrails, and AI doomerism, which wants a complete deployment moratorium,” she says. “Both positions prevent people from reasoning critically about the opportunities and risks in these tools.”

WHAT’S BEHIND THE MAGIC

UW–Madison students needn’t go far to learn about the latest in AI from an in-demand engineer. Professor John Lee was on sabbatical at Apple last year and is now finishing a research project with NASA to develop conversational AI agents that measure and manage the trust that a human has in them. Their end destination? Mars.

“It’s to support teams doing deep space exploration, where they can’t easily contact Houston when they have a problem,” Lee says. “If you’ve seen the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, it’s very much like designing [the supercomputer] HAL.”

In his course Industrial and Systems Engineering 602, students are tasked with developing their own AI applications by the end of the semester. You’d think that would require a lot of technical coding experience, but Lee notes that you no longer need to be fluent in the programming language Python. Now you can ask an AI tool like Gemini to write lines of code for you.

Lee teaches “what’s behind the magic,” focusing on how AI models are built and how they function so that students can use them effectively. The title of the course, AI for People, underscores the importance of designing technology around human-centered needs: to enhance our productivity rather than replace it, and to think through all the potential consequences of our decisions.

“You can give [the AI assistant] Dot your calendar, and it can remind you to give your mother a call on her birthday,” Lee says. “It’s like an assistant or companion. But if you design it in a way that automates that relationship, you can imagine Dot just buying flowers for your mother and you see the bill, or Dot calling your mother and impersonating you. Those are things that undermine your agency and automate you out of the process.”

“People who can work well with AI will succeed, and those who can’t will be in deep trouble.”

A hot topic around AI is its propensity to hallucinate and provide, with complete confidence, a demonstrably wrong answer. In one class, Lee tasks students with “tricking” AI. One student gets it to describe a nonexistent academic paper that she supposedly cowrote. Another asks for a list of famous people who have spoken at the UW. It wrongly includes Bill Gates, and when prodded about the topic of the speech, confabulates an entire story.

The students learn they can minimize hallucinations as a user by uploading supporting documents along with the written prompt — allowing AI to process new information instead of only relying on its original training data.

Even Lee is routinely awed by the growing capabilities of generative AI. To help me prepare for the class, he shared a podcast episode that explored the themes of his syllabus. It sounded just like any other tech podcast, from the engaging, informative breakdown of the topic to the natural, friendly banter between hosts. It took me 15 minutes to realize it was an AI podcast. Lee had generated the audio in a few seconds by opening Google’s NotebookLM, attaching the syllabus, and pressing a button.

GETTING THE MESSAGE

At the start of the semester, Lee was troubled to learn that a few of his students had avoided AI for fear of being accused of cheating or because of other concerns.

“People who can work well with AI will succeed, and those who can’t will be in deep trouble,” Lee says. “If you’re 10 times as productive as your coworker, guess who’s going to have a job at the end of the year when they have to make some cuts?”

Annika Hallquist, the master’s student whose undergrad experience was split in half by the emergence of generative AI, has heard his message loud and clear.

“On the very first day of class,” she says, “Professor Lee told us, ‘I don’t think jobs are going to be replaced. But I think people are going to be replaced with people who know how to use AI.’ ” •

Preston Schmitt ’14 is a senior staff writer for On Wisconsin.

Published in the Summer 2025 issue

Comments

Bob Lund June 11, 2025

I enjoyed your article “Quantum Leaps In Education”.

The area of AI’s role in education is very interesting to me. In particular, the area of programmed learning or programmed instruction.

In the late 1970’s I began my years as an IBM engineer learning about their hardware and software utilizing primitive programmed learning on a “time-sharing” computer terminal.

These “graded online classes” were primarily used as primers to traditional hands-on classes. There was little or no accompanying video presentation at that time.

Imagine what could be done today with AI driving this kind of educational supplement.

JAMES CARLINI June 15, 2025

As I say in my article – “We cannot keep teaching checkers when the world has moved forward playing chess.”

AI is definitely an area we need to develop a lot of skills in, not just in higher education. We need to rebuild the institution of public schools and begin to introduce AI concepts and skills at a much earlier age if we want to compete in tomorrow’s economy.

We must rethink Education in the Age of AI.

https://intpolicydigest.org/the-platform/rethinking-american-education-for-the-age-of-ai/