Catching Cold

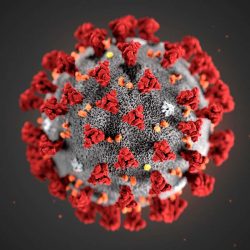

Virologists sequence the genome of the common cold.

Working with a team of researchers at the University of Maryland, UW biochemistry professor Ann Palmenberg has penetrated one of the most confounding mysteries that plague the human sinus: the common cold.

In February, the scientists announced that they had successfully sequenced the genome for all known varieties of the human rhinovirus (HRV), which causes the upper respiratory infection commonly called a cold.

While common, the cold itself presents something of a mystery. Although the virus was identified decades ago, little progress has been made in understanding its inner workings — which has left doctors in the dark about a disease that affects almost everyone.

“The lack of whole-genome sequence data for the full cohort of HRVs has made it difficult to understand basic molecular and evolutionary characteristics of the viruses and has hampered investigations for the epidemiology of upper respiratory tract infections and asthma epidemics,” Palmenberg and her colleagues reported.

The common cold, they argue, is more than an irritant. Americans, they note, spend some $6 billion on cold medication each year. Further, colds cause approximately half of all asthma attacks, and the virus can cause infants to develop asthma.

What makes HRV so difficult to deal with is its variety. There are some ninety-nine known strains of the virus, categorized as falling into two distinct species: seventy-four strains of the species called HRV-A and twenty-five of HRV-B. By sequencing these viruses, the researchers hope that scientists will be able to understand what makes them so pathogenic.

Further, increasing knowledge of HRV-A and HRV-B may help improve understanding of a newly discovered species called HRV-C, a virus that appears to cause far more serious infections deeper in the respiratory tract.

Palmenberg notes that the gene-sequencing project doesn’t mean that a cure for the cold will appear anytime soon.

“Nobody cares about curing HRV-A and HRV-B,” she says. “They don’t cause particularly dangerous disease, and the safety issues involved in even testing a vaccine take that option off the table.”

But she notes that the project may lead to antiviral agents or vaccines against HRV-C. “Type C is the real deal,” she says. “It produces flulike symptoms that often develop into dangerous viral pneumonia.”

Published in the Summer 2009 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.