Nobody’s Senator but Ours

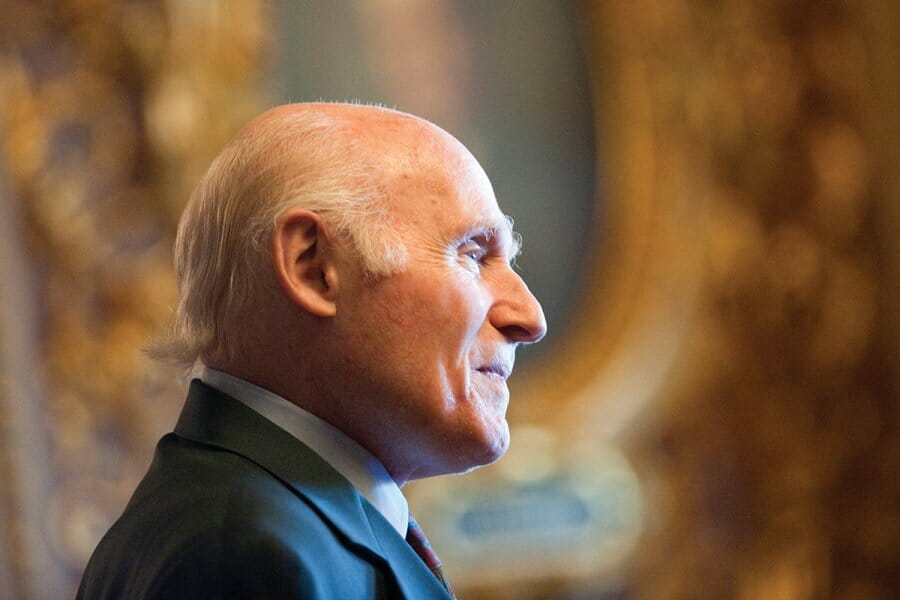

After a quietly effective political career, Herb Kohl ’56 is helping UW–Madison find practical solutions for an ailing democracy.

Herb Kohl ’56’s steadfast commitment to finding common ground made him one of the most successful problem-solvers in the U.S. Senate. His nearly compulsive modesty also made him one of the least known.

That is, except to Wisconsinites, who rewarded his earnestness by electing him to four terms from 1989 to 2013. He was, according to his famous campaign slogan, nobody’s senator but theirs.

Former colleagues of Kohl, fellow Democrats and rival Republicans alike, invariably describe him as gracious and honest, quiet but effective, and above all, dedicated to Wisconsin.

A decade after he left office, with Washington consumed by partisanship and gridlock, Kohl’s soft touch in the Senate seems almost archaic. But always an optimist, he continues to work behind the scenes to promote practical solutions to society’s problems. In 2019, he donated a record $10 million to the UW’s La Follette School of Public Affairs. The gift has already proved transformative for the school, boosting its efforts to train future leaders and advance the public good.

“I think we are seeing all of our greatest fears right now. The chaos, the disregard for truth and facts, the unwillingness to listen and talk to each other,” Kohl says. “But my greatest hope is in the fact that we are still a democracy in the greatest country in the world. I think we can look to appeal to our better angels and come together if we make the effort.”

Kohl, 87, believes he still has a debt to pay off, despite decades of public service and hundreds of millions of dollars in philanthropic gifts. It’s the debt he feels from having had such good fortune in his life. In his first stump speech in 1988, he noted that wealthy people have a “special responsibility to those who are not as comfortably well off” — those like his parents, European Jewish immigrants who came to America with nothing and built a business empire that set the stage for one of Wisconsin’s most beloved public servants.

The American Dream

The Kohl family’s American dream began 100 years ago. Kohl’s father, Max, emigrated from Poland, and his mother, Mary, from Russia. They left behind many family members in Europe who later lost their lives to the Holocaust.

Struggling to find their way in Milwaukee, the couple decided to open a corner food market beneath their southside apartment in 1927. Their English was so poor that customers had to point at the items they wanted to purchase.

Max and Mary Kohl often discussed social justice at the dinner table with their kids.

“They always looked forward to the future with optimism and determination,” Kohl says. “And they showed us that your life would be measured far more by what you contribute than by what you have.”

In 1946, at age 11, Kohl cut the ribbon at his family’s first supermarket, which would soon expand to multiple locations. In 1962, the family opened the first Kohl’s department store. It’s now the largest such chain in the United States with more than 1,000 stores.

“My greatest hope is in the fact that we are still a democracy in the greatest country in the world.”

Kohl grew up with his sister and two brothers on 51st Boulevard in the Sherman Park neighborhood. A few hundred feet away on 52nd Street lived Bud Selig ’56, the future commissioner of Major League Baseball. They met in early grade school and have remained best friends for more than eight decades. They still meet for lunch almost every week, calling each other only by their last names.

“We have a lot of great memories, fun and funny stories, and maybe even a bit of a shtick,” Kohl says.

They bonded over sports from an early age, and Kohl delights in sharing the story of how the two faced each other as captains of their respective baseball teams in the sixth grade. In Kohl’s telling, Selig recruited a towering 6-foot-something stranger to pitch in the championship game. Kohl’s team struck out at every at-bat and lost 9–0.

“He has a wonderful imagination,” Selig says, laughing.

The two friends found their way to the UW for what Kohl calls the best four years of his life. Both he and Selig studied history and political science, roomed together, and joined the Jewish fraternity Pi Lambda Phi.

Kohl (right) with best friend Bud Selig in the 1955 Badger yearbook. He calls his UW experience the best four years of his life. UW Digitized Collections

At the UW, Selig became close friends with Charlie Thomas ’57, a Black football player, and encouraged him to join the otherwise all-white fraternity. It was a radical notion in the 1950s, but Kohl immediately offered his support.

Thomas’s pledging was controversial both inside and outside of the fraternity house. But on the night of the vote, which lasted until 2 a.m., Selig and Kohl deployed the persuasive skills that would later define their careers. They convinced their peers to integrate the fraternity. Thomas went on to a successful career as superintendent of North Chicago schools.

Kohl still holds dear the values his immigrant parents instilled in him: integrity, humility, determination, kindness, hard work, resilience. They’re the same ones that made him one of Wisconsin’s most respected employers and policymakers.

“He’s Unique”

After he graduated from the UW, Kohl earned an MBA from Harvard, joined the Army Reserve, and became president of the Kohl’s Corporation, which had expanded to 50 supermarkets and several department stores.

Taking after his father, Kohl continued to run the rapidly growing chain as if it were still a small mom-and-pop shop. He conducted many job interviews himself, believing that employees would be more loyal if they were hired by a Kohl family member. He made the rounds to every store, inspecting the tidiness of food displays and even bagging groceries for customers during busy times.

“With any store we walked into, he knew every employee by their first name, and he knew all their families,” Selig says. “You could tell his whole heart and soul was into it.”

Employees stayed for years, if not their entire careers. They had their own credit union and health insurance. They had five weeks of paid vacation. They received employee discounts and grocery coupons to buy Christmas dinner for their families.

“Our employees were extensions of our family,” Kohl says.

The family sold the business in 1979. Almost a decade later, when Kohl first ran for office, many former employees championed their former boss. Mary Carini, who worked for Kohl’s food stores for 10 years, was a registered Republican but volunteered for Kohl’s 1988 Democratic campaign, still touched by how he checked in on her during her divorce.

“He’s unique,” she told the Capital Times. “I never knew a businessman of his caliber of intelligence and drive, yet so compassionate toward people.”

It didn’t hurt Kohl’s political prospects that he was the savior of the state’s professional basketball team. Milwaukee Bucks owner Jim Fitzgerald announced in 1985 that he was selling the franchise, lamenting that its arena had the lowest seating capacity in the National Basketball Association (NBA). Kohl feared a sale to out-of-town bidders.

“I knew I needed to step up and do what I could to keep the Bucks here,” says Kohl, who bought the team for nearly $20 million.

Kohl preserved the Bucks yet again in 2014. He sold the franchise with the contingency that the new owners make a long-term commitment to Milwaukee. He also donated $100 million to the construction of a new arena to help make that a reality.

And Kohl arguably deserves as much credit as anyone for the team’s 2021 NBA championship. It was under his ownership that the Bucks drafted league MVP Giannis Antetokounmpo and traded for all-star Khris Middleton.

Kohl still holds dear the values his immigrant parents instilled in him: integrity, humility, determination, kindness, hard work, resilience.

Before the championship parade, a TV reporter told Kohl that he made the moment possible by saving the team. Kohl, looking as always like he wanted to be anywhere but in the spotlight, responded simply: “Well, that’s nice to hear. I was one of many.”

Such implausible humility is familiar to anyone who knew him as a senator.

A Nonpolitical Aura

It’s one of the most effective and imitated slogans in recent political history: “Nobody’s senator but yours.”

“Voices of special interests were drowning out the voices of ordinary citizens,” Kohl says of his first Senate run in 1988. “And I made the pledge not to accept contributions from political action committees or other special interests.”

As he stated at his campaign kickoff event: “The important thing is that when the campaign is over, I will owe nothing to anybody but the people of Wisconsin.”

Crucially, Kohl’s everyman personality made it believable that he couldn’t be bought. He often wears the same navy-blue blazer with a faded Bucks cap. Even when he owned an NBA team, he sat with the crowd rather than at courtside. He’s lived in the same Milwaukee condo for 50 years. He prefers to dine at casual “paper napkin” restaurants like George Webb and Ma Fischer’s.

“I think in a lot of ways he was always seen as a guy with Wisconsin at the forefront and as a businessman at heart,” says Scott Klug MBA’90, a former Republican congressman from Wisconsin who served with Kohl for eight years. “That gave him sort of a nonpolitical aura.”

Kohl was late to enter the crowded Democratic primary in 1988. At 53, he was a political outsider. He staked liberal-to-moderate positions on issues, overcame a few gaffes, and sailed through the primary, despite criticism about his heavy campaign spending. Kohl won the seat and held onto it with steadily increasing support. In his last Senate race, he carried all 72 Wisconsin counties. He did it by treating public office a lot like his business. But now, five million Wisconsin citizens were his customers.

A Workhorse Senator

He welcomed them all. The office hosted Wednesday morning breakfast for any Wisconsinites who happened to be visiting Washington, DC. The senator would stop by, take photos, and hand out Bucks pens. His aides were on hand to respond to the visitors’ policy concerns or assist them with their travel plans.

“It was mandatory,” says Ben Miller, who served as a legislative aide in Kohl’s office in the early 2000s and now oversees government affairs for UW–Madison. “Every week, we all had to be there with doughnuts and coffee.”

Kohl’s office earned the reputation as one of the best customer service operations in the Senate. If a constituent called about a missing Social Security check, his staff would promptly track it down. Every phone call was returned, and every letter answered.

Behind the scenes, Kohl was one of the Senate’s biggest (if quietest) players, sponsoring or cosponsoring more than 3,000 pieces of legislation over his career.

“He saw it as his job to give a voice to people who need to be heard in Washington — children, working families, and farmers. I think when you ask people what they want public service to be, Herb’s legacy is a shining example of what it can and should be.”

With gun violence on the rise in the ’90s, he negotiated a series of bipartisan gun-control measures. He authored a bill banning guns in school zones. When the Supreme Court overturned it on a technicality, he rewrote the legislation to address the loophole and prohibit guns within 1,000 feet of schools. He also cosponsored the Brady Bill, which required an instant background check and a five-day waiting period for the purchase of handguns.

Such bipartisan compromises on a hot-button issue were anything but inevitable. In July 1998, Kohl wrote legislation mandating that manufacturers include child-safety locks with the sale of handguns. He allowed California senator Barbara Boxer to serve as the lead sponsor of the amendment, which the Senate rejected on a 39–61 vote. Less than a year later, Kohl introduced a nearly identical proposal. It passed 78–20.

“We used to call it the ‘Herb Kohl Vote Count’ in our office. There would always be more support than projected when Senator Kohl held a floor vote because his colleagues on both sides of the aisle trusted him,” says Jon Leibowitz ’80, a former chief counsel for Kohl who later became chair of the Federal Trade Commission. “Everyone knew he was doing it for the right reasons, and they would want to vote with him.”

With a soft voice, shy demeanor, and short stature, Kohl rarely commanded the room. But when he did talk, his colleagues knew to listen.

Republican senator Chuck Grassley told Milwaukee Magazine in 2010: “I’ll bet he never has done anything to harm or hurt anybody behind their back.” He added that he probably talked to Kohl less than to any other senator, and yet accomplished more with him than anyone else.

“Since I came from the world of running a business, politics to me has always been based on working hard, finding common ground, and getting things done,” Kohl says. “It often means being willing to meet in the middle.”

Over 24 years, he cast his fair share of controversial votes. He voted to prohibit same-sex marriage in 1996 but against a constitutional ban in 2006. In 2002, he supported the resolution to authorize the use of military force in Iraq.

“I had misgivings at the time but ended up voting in favor,” he says. “I was wrong.”

After his fourth term, Kohl retired from the Senate in 2013. His colleagues lined up to recognize his legislative achievements around public education, health care, child and senior care, consumer rights, and Wisconsin’s dairy industry. One called him “a classic workhorse senator, as opposed to a show horse senator.”

“He saw it as his job to give a voice to people who need to be heard in Washington — children, working families, and farmers,” says Tammy Baldwin JD’89, who won Kohl’s Senate seat after he retired. “I think when you ask people what they want public service to be, Herb’s legacy is a shining example of what it can and should be.”

Leading by Example

Kohl’s father once told him the old adage “Money is like manure; it’s not good unless you spread it around.” Kohl has made a habit of it.

In 1990, he started the Herb Kohl Educational Foundation, which has provided more than $30 million in grants and scholarships to Wisconsin students, teachers, and schools. His main charitable entity, Herb Kohl Philanthropies, has awarded thousands of grants to nonprofits that support educational and economic opportunity.

“My parents taught me the immeasurable value of a good education,” Kohl says. “Education is an investment with the greatest return. It is also the great equalizer.”

After the UW struggled for years to fund a new sports facility to augment the aging Field House, Kohl stepped forward with a $25 million lead gift in 1995 for the basketball and hockey center that still bears his name.

And now he has turned his attention back to policymaking. In 2016, he gave a $1.5 million gift to the UW’s La Follette School of Public Affairs to establish the Herb Kohl Public Service Research Competition, which supports evidence-based policy and governance research by faculty members and students. Topics have ranged from childhood poverty and solar energy to water quality and opioid prescriptions.

Encouraged by its success, Kohl donated $10 million in 2019 to boost the school’s outreach, teaching, and research efforts.

“Our democracy is being threatened by bitter partisanship, and the La Follette School is poised to lead by example — fostering cooperation, respectful discourse, and service to others,” Kohl said at the time.

The school now hosts the annual La Follette Forum, convening hundreds of lawmakers and leaders to discuss timely policy topics and bridge partisan divides. It’s launched a poll to capture Wisconsin residents’ thoughts on policy issues. And it’s holding several community events across the state this fall to share policy research and enhance public discourse.

“At UW–Madison, we’re not just convening conversations,” says Professor Susan Webb Yackee, director of the La Follette School. “We’re creating the research that identifies major problems and connects them to solutions. We’re educating future leaders whose public policy skills will translate to government action.”

With Kohl’s support, the UW is becoming an incubator for practical solutions and a setting for common ground. To say he’s fighting an uphill battle may be the understatement of this political decade. Congress — and much of the country — has doubled down on partisanship and division.

Is it too late?

“I have to believe that there’s still room in today’s political environment for people like Senator Kohl,” says Miller, his former legislative aide. “Otherwise, I’m not sure how I would get through the day. I don’t want to lose hope. And part of that optimism is because of what he’s instilled in me.” •

Preston Schmitt ’14 is a senior staff writer for On Wisconsin.

Published in the Winter 2022 issue

Comments

Jerry Smith November 29, 2022

Where to start? I have met Herb but so have majority of Wisconsin residents at one time or another. He travelled the state endlessly not unlike Bill Proxmire. I love watching people and politics. There is not enough room to add his accomplishments and the people he helped. I needed help once with aging parent situation and reached out to him. He did not as about party affiliation. (Today I consider myself non partisan.

I served many years on the Aldo Leopold B0ard and reached out to Herb for a favor and of course he called me personally. I’m sure he never heard of me before.

If ever there was a role model in this day and age , he is the man.

Jim Schuster '80. Winter Park,Fl December 3, 2022

Great article on Senator Kohl. It brought back a very vivid memory of my interaction with the man. My first job as a 16 year old was as a grocery bagger at the Kohl’s Food Store on 35th Street in Milwaukee in 1974. As part of the “official” training, I was advised by the seasoned veterans that if you ever heard the codeword “Herbie”, you immediately dropped what you were doing, ran up to the checkout lanes and performed at your very best. This meant that there was a sighting of Mr. Kohl, who had a propensity for observing customer interactions and providing his feedback.

Sure enough, on my THIRD night on the job, everyone is whispering”HERBIE !! “. I remember seeing this very distinguished and well dressed man walking in to the store. We probably had four or five checkout lines open at the time and he immediately makes a move towards my line. Standing two feet behind me he starts small talking with the cashier and then with the customer. I have no idea what was said because I could only hear my rapidly accelerating heart beat. After what seemed like an hour, I finish bagging the order and saying Thank You to the customer. I get a tap on the shoulder, I turn around, and Mr. Kohl says “Fine job, young man”.

Thanks for that, Mr. Kohl ,as those four simple words meant an awful lot to a scrawny 16 year old kid.

Jim Schuster '80. Winter Park,Fl December 3, 2022

Thanks for the great article on Senator Kohl. It brought back a very vivid memory for me. My first job as a 16 year old was as a grocery bagger at the Kohl’s Food Store on 35th Street in Milwaukee in 1974. As part of the unofficial training process, I was advised by my seasoned co-workers that if I ever heard anyone saying the codeword “Herbie”, that I needed to immediately drop what I was doing, head to the checkout area and look sharp. This meant that Mr. Kohl has been sighted and he had a propensity for being very thorough in his observations of customer service.

On only my third night on the job, I hear the loud whispers of “HERBIE”. I was already up front bagging groceries and I see this swarm of co-workers running to the front of the store . In walks this very distinguished and well dressed man who is greeted by the store manager. At this point, we probably have 6 checkout lines running, and much to my surprise, he walks directly to my lane. Standing 2 feet behind me, he starts a conversation with the cashier and then with the customer. I have no idea what was said. The only sound I could hear was my heartbeat. After what seemed like an hour, I finish bagging the order, placing it in the cart and thanking the customer. Then, a tap on the shoulder. I turn around, and he said, “Fine job, young man.”

Thank you, Mr. Kohl. Those four simple words meant quite a bit to a scrawny 16 year old kid.

Bill Ritz November 4, 2023

Simply, a great, kind, humble man and good friend. Herb always put his constituents and country first.

Cunshan Wang January 2, 2024

I wholeheartedly concur with the statement in the article “Kohl’s office earned the reputation as one of the best customer service operations in the Senate. If a constituent called about a missing Social Security check, his staff would promptly track it down. Every phone call was returned, and every letter answered.” and the campaign slogan “Nobody’s senator but yours”.

While studying at UW-Madison in the early 90’s, I invited my mother-in-law who resided in China at the time to visit us. However her visa application was rejected twice by the Shenyang Consulate General. Out of desperation, I wrote to senator Kohl and to my surprise I received a letter from him in support of my mother-in-law’s visitation along with a letter addressed to the Shenyang Consulate General. Needless to say, my mother-in-law’s third visa application was granted and she enjoyed very much of the visit to us. Senator Kohl’s help in the time of need meant a great deal to my family.