Michael Finley: The Sequel

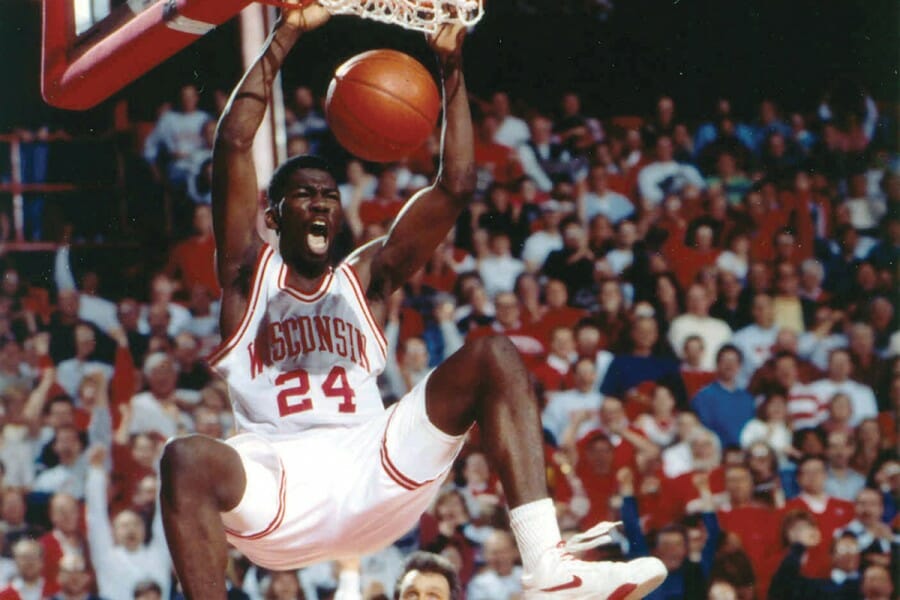

With one foot in basketball and another in Hollywood, the former Badger star writes his next chapter.

On the hit show Shark Tank, billionaire Mark Cuban urges would-be entrepreneurs to “follow the green, not the dream.” Former Badger basketball star Michael Finley ’14 is doing both.

After nine seasons with Cuban’s Dallas Mavericks and 16 total in the NBA, Finley has learned the business of the sport and now serves as the team’s assistant vice president of basketball operations. He’s also launched a career as a film producer, making movies that tell stories Hollywood has ignored, yet still have the potential to turn a profit.

In February, The First to Do It was released in theaters nationwide. A documentary Finley produced about Earl Lloyd, the first African American to play in the NBA, it premiered last year during the NBA All-Star Weekend in New Orleans. “There’s a lot of guys in the NBA of African American descent who have never heard of Earl Lloyd or don’t know the significance of him in NBA history,” Finley says. “They’re playing the game that they love because of guys like Earl Lloyd who broke those boundaries down.”

The documentary follows the critical and commercial success of the Finley-produced American Made, which starred Tom Cruise. The movie, made for $50 million, grossed more than $130 million at the box office after its October 2017 release.

A two-time NBA All-Star, Finley is also an active philanthropist who has endowed an athletic scholarship at the UW and is building up a charitable foundation that works to help kids in the Dallas–Fort Worth community avoid the “summer slide” and make strides in school.

“What Would You Do with Life after Basketball?”

That’s the question Finley’s business manager posed to him as his NBA career was winding down in 2009. Finley had harbored an interest in both real estate and the entertainment industry, so his lawyer set up a meeting with a successful film producer. The conversation left Finley amazed and intrigued by what went into making a movie. “The rest is history,” he says. That same year, Finley started Follow Through Productions. He has 10 credits to his name as a producer, including Lee Daniels’ The Butler and The Birth of a Nation, and he’s clear about his decision-making process for getting involved in a production. “First of all, for me it’s a business, and it has to make financial sense for me,” he says. “But even more important than that, the story has to resonate with me.” Finley reads every script he receives and says he has to be “in awe” of it and able to imagine what it would look like on the big screen. “If the script has that kind of effect on me, then I go to the next stage and try to see if it makes financial sense. And if those two things go hand in hand, nine times out of 10, I’ll usually do the movie.”

“It Keeps the Competitive Fire Going in Me.”

With the Mavericks, Finley evolved into a team leader who could bring calm to a locker room. “He’s the one guy on the team, when he opens his mouth, everybody shuts up and listens,” a team insider revealed to Sports Illustrated in 2002. Finley says he brings that strength to his front-office position with the Mavericks. “When I’m talking to either Mark [Cuban] or scouts … they respect what I have to say, because they know I’m not just saying some stuff just to hear myself speak. There’s substance to it.” But Finley’s confidence also comes from what he learned about the business of professional basketball while spending two years essentially interning for Cuban before being named to his current role. “As a player, you think you know everything, and once you get on this side, you realize that you really don’t know anything,” Finley says. “It’s like going back to school and learning, and it’s been a great journey for me.” One lesson: the complexities of player contracts. “I always thought that if Player A made $1 and Player B made $1, you can trade them for Player C who makes $2 — but it’s not that easy. There’s a lot of rules and regulations that go into trading for a guy.”

“You Have to Dive Deeper.”

Finley has run the draft for the Mavericks the past two years. As more players enter the draft at a younger age, teams have to do more than study game film or scout in person to make smart choices. The job requires Finley to do in-depth research to “try to find out as much as you can about that person as a basketball player and as a young man. … We’re investing a lot of money into these individuals, and you just don’t want to go in blind.” Finley’s efforts have impressed his boss. “He’s been one of the smartest moves I’ve made in a long time,” Cuban told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram after the 2016 draft. “We’re becoming more and more dependent on him.”

“This Is Home.”

Even though Finley left the Mavericks for the San Antonio Spurs in 2005 after Cuban waived his contract for salary-cap relief, he has long considered Dallas home. (His wife, Rebekah, is from Fort Worth.) “When I played [in Dallas], the community embraced me with open arms. I did a lot of community service in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, so it always had a special place in my heart,” he says. After his family returned to Dallas, Finley reinvented his approach to giving back to the community that embraced him as a player. Last summer, his foundation, which he established in 2003, provided instruction in core academics, computer programming, fine arts, and life skills to 19 students in third and sixth grade, and offered tutoring and parent education throughout the school year. “Statistics show that during the summer, kids either stay the same or forget what they learned the previous year … so we’re trying to limit that,” he says. “The goal is to follow those kids, not only through the summer, but throughout the school year and then bring those same kids back … then enroll a new flock.”

“When I’m talking to either Mark [Cuban] or scouts … they respect what I have to say, because they know I’m not just saying some stuff just to hear myself speak. There’s substance to it.”

“It Was Something I Promised My Mom, Something I Promised Myself.”

When Finley first arrived at the UW as a freshman, his plan was to pick up enough extra credits during summer school to graduate in four years, “but because of basketball, my summers were booked,” he recalls. He left campus in 1995 as the Badgers’ all-time leading scorer and was drafted by the Phoenix Suns. “I talk to kids all the time about the importance of education, and I felt kind of like a hypocrite when I was telling these kids to ‘get your education, get your college degree,’ but I didn’t have mine,” he says. Between online classes and taking courses at a local college, Finley reached his goal. In 2014, he received his degree from the UW in agricultural and applied economics. His mom, sisters, wife, and children were on hand. “It was a great time — not only for me, but for my family and for all the kids who look up to me as well,” he says.

“The Four Years That I Had at Madison … Were the Best Four Consecutive Years of My Life.”

Finley lives out of a suitcase for periods of time, traveling with the Mavericks for about 85 percent of the team’s road games. But he found time to return to Madison last fall with his wife and three children for a visit, which included a stop at Mickies Dairy Bar. “People who haven’t been on campus or who don’t know much about Wisconsin always ask me, ‘Why did [you] go to Wisconsin?’ I say if you go to Wisconsin and spend a week there, getting to know the people at the university and in the community, you’ll realize why: because it’s a loving place, a place that truly loves not only the athletes, but also their students. To this day, I can travel around the world and always see someone from Wisconsin, and it’s a great family to be a part of.”

Jenny Price ’96 is co-editor of On Wisconsin.

Published in the Spring 2018 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.