Making It Count

How can we reform the American voting process?

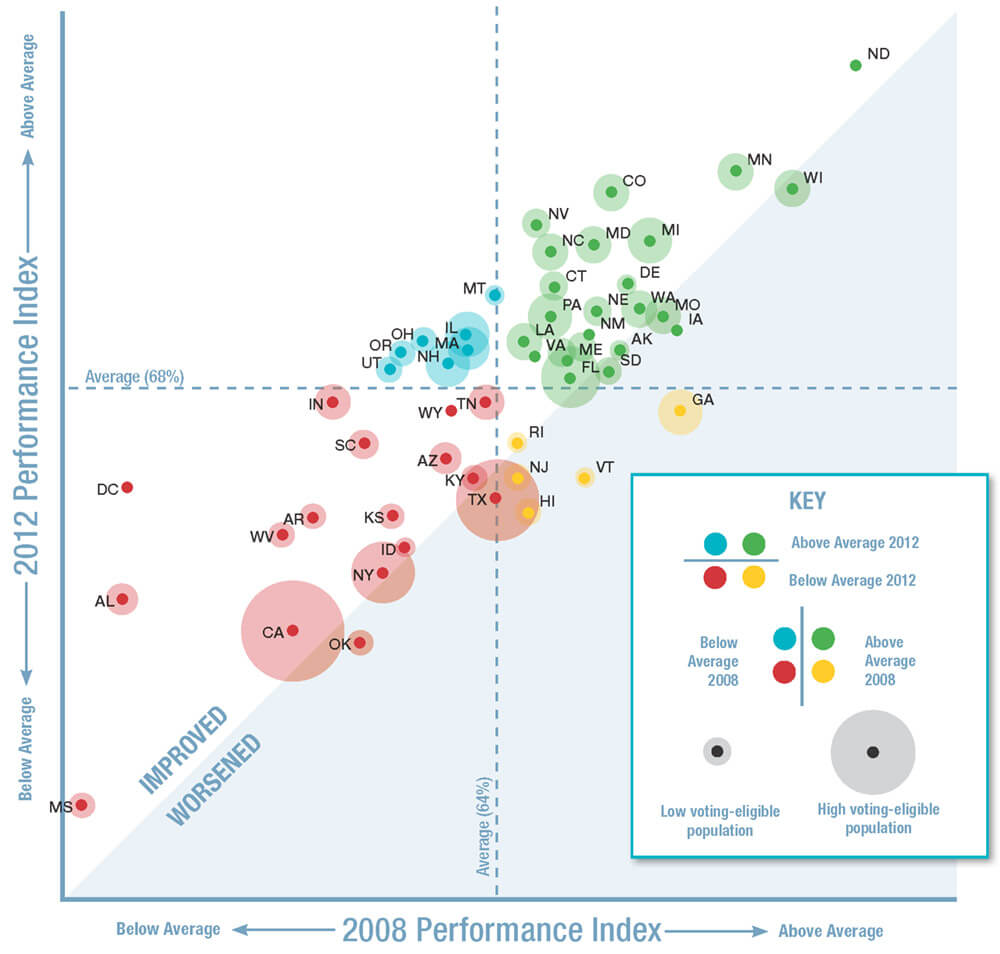

HOW GOOD IS YOUR ELECTION? This Pew Elections Performance Index is based on 17 measurable indicators, including wait time at polling locations, number of rejected voter registrations, voter turnout, and accuracy of voting technology. UW political science professor Barry Burden was a member of the study group that created the index. Courtesy Of Pew Charitable Trusts.

After President Obama was re-elected in 2012, he thanked Americans who voted, including those who stood in long lines at polling places, waiting for hours to cast their ballots. “By the way, we have to fix that,” he said.

Obama made good on that unscripted remark by establishing a presidential commission charged with studying ways to improve elections. UW–Madison Professor Barry Burden was one of the political scientists named to serve as a researcher for the group, which earlier this year released recommendations on how to shorten waiting times, accommodate voters who don’t speak English, and staff polling places.

Since the 2000 election landed at the U.S. Supreme Court due to voting problems in Florida, states have been experimenting with and reforming the voting process. Burden says change has come in waves, from buying new machines to expanding early voting. In recent years, however, some states (including Wisconsin) have imposed restrictions on early voting and are fighting in court to require a photo ID to cast a ballot.

In a new book, The Measure of American Elections, Burden and his colleague Charles Stewart III, a professor at MIT, make the case for moving beyond voter anecdotes and media reports to find a more accurate answer to the question: just how good are American elections? They contend that we need a scientific, data-driven approach to studying how elections are administered — just as we analyze criminal justice, education, public health, transportation, and other government functions. And more transparency can only make the system stronger, Burden writes, noting, “People are more likely to participate if they are confident in the system and find it relatively easy to take part.”

So what do we know about voting in America?

When it comes to voting, no state is the same. The voting system in the United States is a patchwork of different registration and voting practices. In Oregon and Washington, for example, residents cast all ballots by mail. Some Eastern states, including Pennsylvania, do not have early voting, and people must vote at polling places unless they have an official excuse, such as a medical problem or military service. In Arizona and California, some polling places are in private homes. “If a person doesn’t move around from state to state, they don’t realize just how much change there is from one place to another. Voters get treated differently depending on where they live,” Burden says.

The federal government does not have a national voter registry. When a voter changes his or her mailing address, voting registration doesn’t also get updated — although many voters think it does. “The idea of national registration is one of those areas where the public is often misinformed,” Burden says. “You can imagine people no longer being registered because they think, ‘Oh, it’s been updated. I told the postal service. They’ll tell the voting people.’ Doesn’t happen.” Burden is part of a research project that includes a small group of states that are sharing voter registration files in an effort to find duplicate registrations and cancel old ones. In the absence of a national list, Election Day registration, which exists in ten states and the District of Columbia, could keep voter rolls clean and up to date. “You just fix that problem on the spot,” Burden says. Many voting machines are nearing retirement. Punch cards with hanging chads and butterfly ballots became extinct after the 2000 election, but they shed light on outdated and ineffective voting procedures. “We purged all those crummy old machines,” Burden says. But although Congress designated money that states used to buy new machines a decade ago, many of them now need replacing, and many of the companies that sold them have gone out of business. And voting machines are not at the top of the list of budget priorities in any jurisdiction. “It’s sort of a perfect storm,” Burden says. As an additional complication, the federal agency charged with establishing standards for voting machines, the Election Assistance Commission, doesn’t have any commissioners and therefore can’t set policies. The president and the Senate have been unable to reach an agreement on those appointments. Absentee ballots are counted. No matter what. A popular myth about absentee ballots is that they are set aside as they arrive via mail and are not counted unless an election is closely contested. Not true, Burden says: “Every vote is counted — every vote that can be counted, where a voter has clearly made a mark that can be read.” You can bank on your smartphone, but don’t expect to vote on it. Internet voting ignites a hot debate. Supporters argue that people should be able to skip a trip to a polling place and vote on a smartphone, but opponents say the risk is too great. Burden points out that “banks have built into their systems a tolerance for fraud,” adding, “Those of us who don’t commit fraud get charged higher fees to help them pay.” With voting, however, the consequences of fraud are different: the election is wrong and irreversible. The vulnerabilities of Internet voting were put on display in 2010, when researchers from the University of Michigan hacked into Washington, D.C.’s online voting system during a test and had the website play the school’s fight song. After that, city officials called off plans for online voting. Registration does not equal turnout. Although about 80 percent of eligible voters are registered in most states, voter turnout varies wildly on Election Day. Minnesota could claim the highest turnout at 75.7 percent in 2012, while Hawaii had the lowest at 44 percent. That disparity, Burden says, can’t be chalked up solely to electoral battlegrounds (although Wisconsin did have the second-highest turnout at 72.5 percent). Some states, such as Mississippi, have a consistently low turnout in part because they do a poor job of running elections. But demographics, which election officials can’t control, play a huge role in turnout. “If you have a state with higher incomes and higher levels of education, you’re going to have more voters, because those are the things that correlate with voting,” he says. Mississippi, for one, has lower rates of education, income, and health — all indicators that correlate with low civic engagement. The reason we vote on Tuesday no longer exists. Early in our history, the United States was a rural, agricultural society. Holding an election was out of the question until after the end of the harvest, which pushed voting into the fall months, Burden says. The date varied across states until a uniform date (the first Tuesday in November) was established for national elections in 1845. But why Tuesday? “We were a church-going people then, so Sunday was not an option,” he says. Factoring in travel time by horse and buggy, Tuesday was the earliest people could get to the county seat to cast a ballot. Today, a national organization called Why Tuesday is pushing legislation to move Election Day to the weekend, but Burden says that shift is unlikely. “It’s not clear voters would use it,” he says.

Published in the Fall 2014 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.