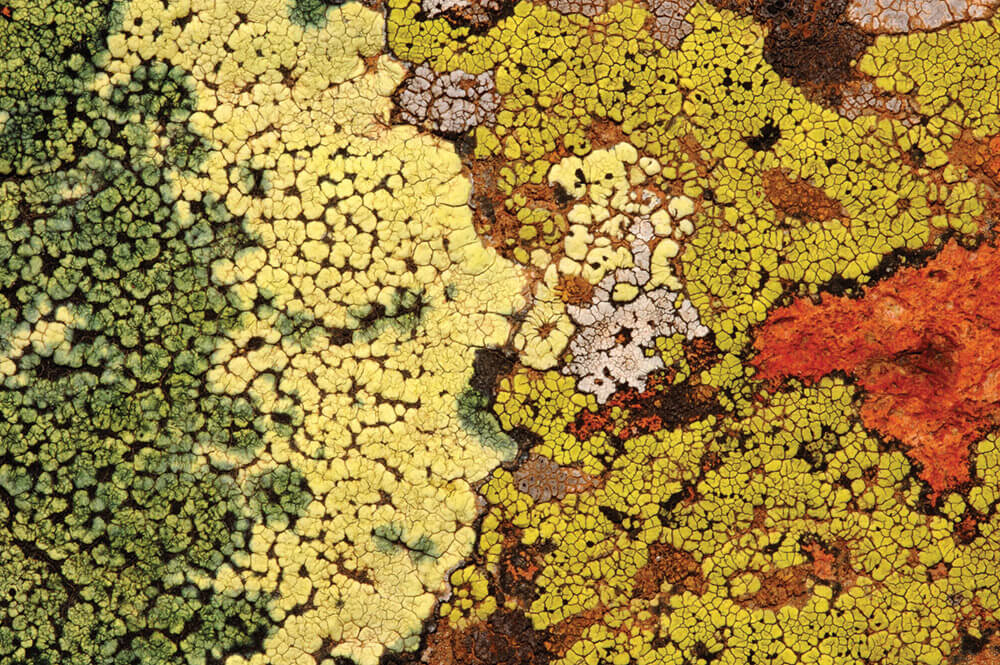

Liking Lichen

Lichens are an important part of the world’s ecosystem. They grow slowly but regularly, so they can be used to date major geological and climactic events. Lichens are also important to the diet of a variety of animals such as reindeer. Shutterstock photo.

The Wisconsin State Herbarium has added 60,000 samples to its collection.

Neatly filed away in drawers in the bowels of Birge Hall, tucked into carefully folded slips of paper, you’ll find bits of rare organisms from around the globe. At home within the Wisconsin State Herbarium, they are part of one of the world’s largest lichen collections — a collection that, in 2014, grew 60,000 samples larger.

A herbarium is a group of preserved plant specimens, and Wisconsin’s dates back to the UW’s founding. At the second meeting of the board of regents — in January 1849, a month before the first class gathered — that august group recommended that the university host a “cabinet of natural history.” Today, that “cabinet” holds more than 1.2 million specimens of plants, fungi, and lichens, making it the eleventh-largest herbarium in the Americas.

The Wisconsin State Herbarium’s lichen collection is particularly strong, with more than 180,000 specimens. Lichens are unusual in that they are composite organisms — they develop through a symbiotic relationship between a fungus and algae or bacteria. Each sample includes not only the dried lichen, but also its substrate — the material it was growing on.

A scientist who studies lichens is called, not surprisingly, a lichenologist, and in the mid-twentieth century, the UW faculty included the man who wrote the book on lichenology: John Thomson MA’37, PhD’39. (Technically, he wrote the books, plural: Lichens of Wisconsin: American Arctic Lichens, volumes 1 and 2, and so on.) He made the herbarium home to a vast variety of lichens from around the state and across the far north.

In 2014, herbarium director Ken Cameron added 60,000 more specimens when he purchased the collection of German lichenologist Klaus Kalb.

“Kalb’s collection includes mostly specimens from the Old World tropics,” Cameron says. “We had to outbid some big competition — Harvard, the New York Botanical Gardens. But we had a lot to offer, including that we could keep his collection together, and it would round out what we already had.”

The herbarium’s materials are shared with researchers around the world. They can then study how the fungi, algae, bacteria, and substrate interact to create a composite. The UW’s lichens are also available for viewing digitally.

Published in the Spring 2015 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.