Mastermind of the Panama Canal

Edward Schildhauer figured out how the make the darn thing work.

Schildhauer’s lock gates were one of the Panama Canal’s major engineering achievements. Wisconsin Historical Society

In 1904, the United States took over an ambitious plan that French engineers had abandoned: working to build a 50-mile canal joining the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through Panama. The advantage? It would cut weeks off the journey between New York and California. The only problem? The Americans had no idea how to actually operate the biggest canal ever constructed.

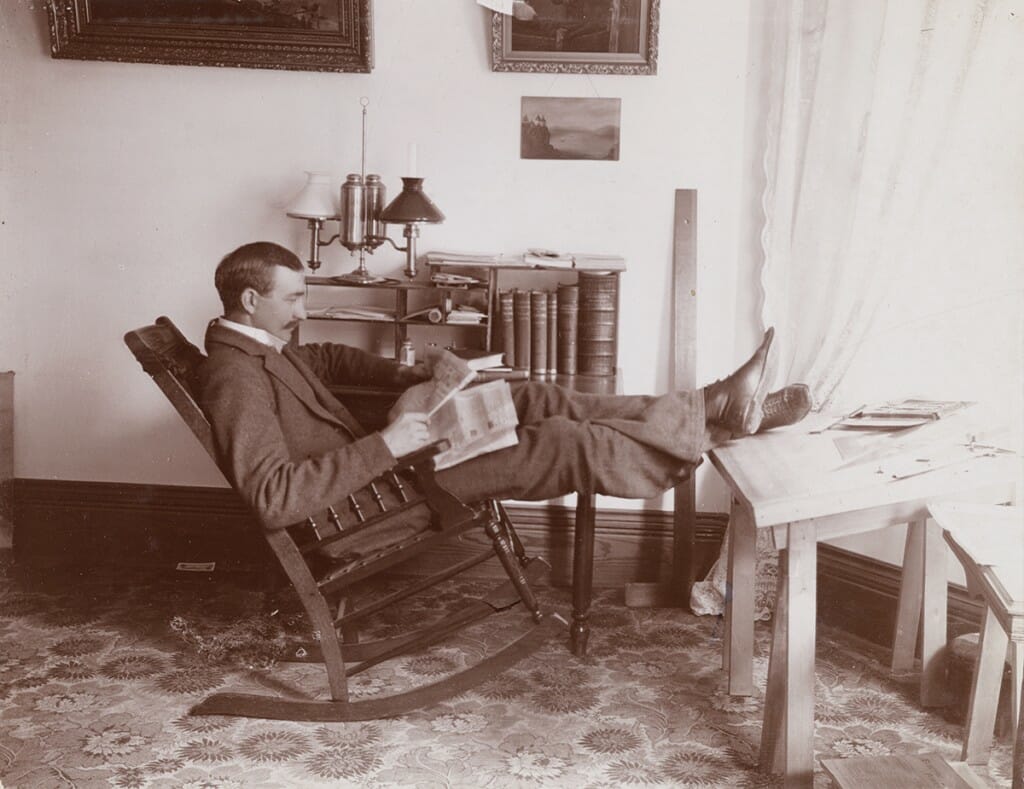

Back in Chicago, an engineer named Edward Schildhauer 1897 was busy inventing arc lights and other construction tools for the Commonwealth Edison Company. Born to German immigrants in New Holstein, Wisconsin, Schildhauer preferred music to science. As a teenager, he taught local farmers to play a variety of instruments and formed the short-lived New Holstein Cornet Band. He also played cornet in an American Cadet band and was the first conductor of New Holstein’s Citizens Band, among other gigs.

The young Schildhauer grew tired of his day job, though, which involved swinging a 14-pound sledgehammer for 50 cents a day. At age 15, he moved to Milwaukee to join an orchestra — and to do even more brutal work: covering steam boilers with sheet metal. During his breaks, Schildhauer watched the switchboard operator and decided it was time for a fundamental career change. He moved to Madison to study electrical engineering at the UW.

It’s unclear exactly how Schildhauer got a job with the Isthmian Canal Commission, but he did so in 1906 and spent a year traveling across Europe to study various canal systems before moving to Panama with his wife, Ruth.

Schildhauer was one of three men who developed the core plans for the canal’s lock system, and he designed the lock gates himself. When the canal officially opened in 1914, the gates were widely considered to be one of the major engineering achievements of the project. They operated using 1,022 electric motors that powered gears as large as 23 feet in diameter, which in turn powered bull gears. Those bull gears moved mechanical arms, which opened and closed the gates as ships were led by towlines controlled by electric locomotives.

This simple yet efficient design automated most of the process of getting a ship through the canal, and it was used until 2002, when the gears were replaced by a hydraulic system. During the almost 90 years that Schildhauer’s locks were in place, more than 800,000 ships passed through the canal.

After Panama, Schildhauer became a business executive and dabbled in politics in Los Angeles. Though he lived in California for 17 years, he was buried in New Holstein when he died in 1953.

Published in the Summer 2020 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.