This Woman’s Work

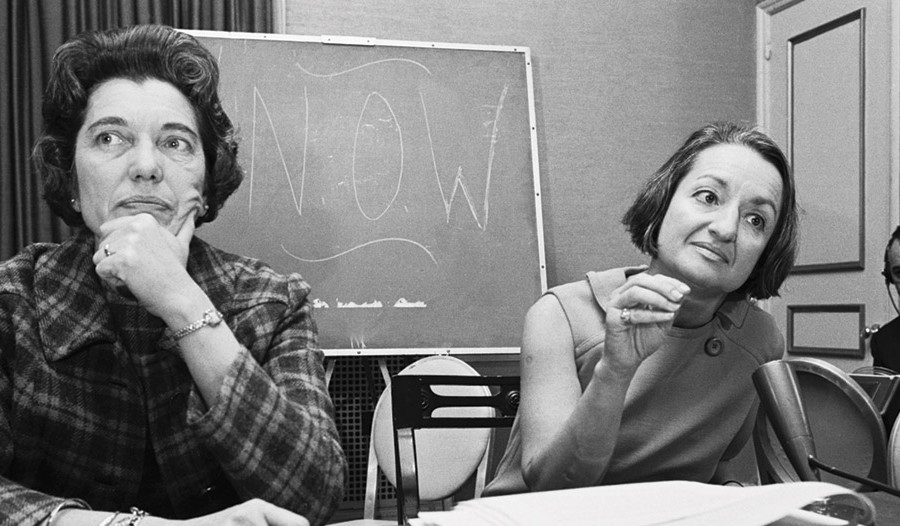

Kathryn Clarenbach built the foundation for the modern women’s movement. Meet the determined feminist you’ve never heard of.

Kathryn Clarenbach started kindergarten at age two and a half and graduated as her high school’s valedictorian at age 16. But when she came to UW–Madison to study political science in 1937, she faced a reality that would strike today’s students as unthinkable: women were not allowed to sit in the Rathskeller.

Her response? After buying her morning coffee at the Memorial Union, she would walk as slowly as the legs on her 5’11” frame could through the Rathskeller to the Paul Bunyan Room, where women were permitted to study. This quiet act of protest was a preview of Clarenbach’s lifelong work, much of which played out in the background of history. By her own account, she was a coalition builder, not a marcher. She was brilliant and fierce, but never the loudest in the room. Yet over time, her persistent efforts at the UW and her work throughout Wisconsin to gain equality for women — which culminated in the creation of the National Organization for Women — formed the backbone of the modern women’s movement.

I polled friends while researching this story, and found that no one had heard of Clarenbach ’41, MA’42, PhD’46. Why isn’t she a household name? Clarenbach never sought the spotlight, never needed to see her name on a bestseller like Betty Friedan, or to stand at the microphone before a rapt crowd like Gloria Steinem. Her reward came from working to change laws and seeing tangible progress toward gaining equality for women.

She was born Kathryn Frederick in 1920, the same year that American women finally won the right to vote. She grew up in Sparta, Wisconsin, in a household where there were no “girl jobs or boy jobs,” she recalled. Her mother, elected to the local school board not long after suffrage, pushed her daughter to pursue her professional interests. Her father, a minister and country lawyer who married thousands of couples in the family’s living room, made a habit of pointing out when a woman was doing something special or unusual.

When Clarenbach returned to the UW to earn her PhD after working for the War Production Board in Washington, DC, during World War II, her department had no female faculty members. She wrote her thesis on “Recent Anti-Democratic Ideas and Tendencies in American Politics,” but noted many years later with some irony that she did so “without word one on sexism or the suffrage movement or any of the rest.”

“The whole nation suffers from the failure to make use of one half of its brainpower and ability.”

In 1963, a presidential commission appointed by John F. Kennedy and initially chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt released a report that included recommendations for improving the civic, economic, legal, and social status of American women. It called for paid maternity leave, universal child care, and ending sex discrimination in hiring, and for courts to recognize women’s equality under the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

By then, Clarenbach didn’t need a government report to tell her about the inequities she and other women faced. Early in their careers, she and her husband, Henry, took jobs teaching at Olivet College in Michigan. She earned half as much as he did, even though she had completed her PhD in political science and he had not. The Clarenbachs returned to Madison in 1960 after she and Henry held various teaching positions in Michigan, Missouri, and New York.

After a brief stint teaching at Edgewood College, the UW hired her to develop continuing education programs aimed at women who no longer had small children at home and wanted a job or something to do outside the home. Hundreds of women responded to surveys or visited her office in person to learn more.

In the summer of 1962, more than 100 women came to Madison to take a noncredit course on the role of women in the modern world. Doing so wasn’t necessarily an easy step. “It seemed almost pathetic to me that competent, able women, in what I’ve always called the best years of their life, would have to say, ‘Is it all right for me to take some of the family money for my own education?’ And then I would say, ‘Yes, it’s all right,’ ” Clarenbach said during an oral history interview recorded by UW Archives in 15 sessions between 1987 and 1989.

As her work at the UW continued, she questioned whether the efforts mattered, writing in a memo to her boss, “I wonder if we are doing a disservice to all of these women, to encourage them to develop their abilities and to broaden their horizons and to add more gratifying things to their life when the outer world is so inhospitable to them?”

In 1964, she convinced Wisconsin governor John Reynolds ’47, LLB’49 to authorize a state commission on the status of women, as the Kennedy report had recommended. She served as its first chair for five years, and again from 1971 to 1979. She traveled across Wisconsin, explaining the commission’s work and giving 30 to 40 speeches a year. “My vocabulary became a little more forceful as I went along,” she said. She drew fire from school counselors when she told them the advice they gave female students limited their options. At a small private college, a female dean told her, “You wouldn’t talk that way if you were married and had children.”

Clarenbach replied, “I happen to be married, and I have three children, and I do talk this way.”

At times, other mothers in her neighborhood pitched in with child care for her son and two daughters. “They knew I was doing something on behalf of women, and they wanted to repay me,” she recalled in her interview. Henry operated a small real estate company and urged her to attend conferences and meetings that would further her work. He shared housekeeping duties and was home with their children after school when she couldn’t be. A 1969 Milwaukee Sentinel article featuring the family includes a photograph of the couple standing in their kitchen — she’s wearing an apron over her professional clothing, and he’s holding a cake he had baked. “I just wouldn’t have known any other kind of marriage, I think,” she said in her UW oral history interview.

Her son, David, who still lives in Madison and served in the state legislature from 1975 to 1993, recalls that Clarenbach was the only mother he knew of who worked outside the home. None of this struck him as unusual. “It was my reality,” he says. “It wasn’t an oddity or something different that required an attitudinal shift. … It was what it was.”

At that time, women who worked outside the home were portrayed as bad mothers. A woman who wanted her name listed alongside her husband’s in the phone book had to pay an additional fee. And a woman who took her teenage child for his or her driver’s test was not allowed to sign the permission form, because the state did not recognize her as the head of the household.

Media and historians may focus on public protests for women’s rights, but the steady work of state commissions is what allowed women to enter the public sphere, laying the foundation for the women’s liberation movement, says Kimberly Voss, a journalism associate professor at the University of Central Florida. Her book Politicking Politely: Well-Behaved Women Making a Difference in the 1960s and 1970s profiles a half-dozen female journalists and political operatives who worked behind the scenes to push for change. “Without them, a lot of what happens in the late ’60s and early ’70s doesn’t happen,” Voss says.

The Wisconsin commission discovered 280 provisions in state statutes that treated men and women differently. “It not only changed my life, it has subsequently become my life,” Clarenbach said of her quest to change state laws that discriminated against women.

Voss, a Wisconsin native, hadn’t heard of Clarenbach until she began researching the role of female journalists in the women’s movement. She spent part of summer 2010 in Madison, poring over Clarenbach’s personal papers at UW Archives, and found that Clarenbach used her influence to get favorable coverage of the commission’s efforts from female journalists who wrote for the so-called women’s pages in Madison, Milwaukee, and Appleton.

By 1966, it was clear that the state commissions had limited power to bring about real change. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), established in 1965 to implement Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, wasn’t enforcing the law when it came to gender discrimination. At the third national conference of state commissions on the status of women in Washington, DC, its members learned the EEOC would not consider a resolution from the group to outlaw the practice of segregating employment ads by gender.

Clarenbach, accustomed to working within the system, was at a crossroads. “For the first time in her experience of women’s rights, she realizes the government isn’t going to help her,” Voss says.

The last hours of the conference laid the groundwork for the creation of the National Organization for Women. Twenty-seven founding members, including Clarenbach, each put five dollars on the table to cover their dues. In the months that followed, however, many women — especially those with government jobs — were reluctant to join the effort. Some sent money, but asked that their names not be listed as members because they feared they’d be fired.

“It seemed too radical,” Clarenbach said. “People were not using the word discrimination. We were talking about disadvantages and obstacles, but nobody used the word oppression, even those of us who were getting this thing off the ground.”

In stark contrast to the positive coverage her work with the state commission received in Wisconsin, national media coverage of women’s efforts to gain equality was abysmal. An editorial in the December 1968 issue of Life magazine referred to the women asking for enforcement of civil rights law as “a group of militant ladies.” Media coverage also reinforced the myth that the women’s movement rose from the East and West Coasts. But Midwestern women were the heart of NOW. A core group, including Clarenbach, was humorously known as the “Wisconsin Mafia” among the movement’s leaders, according to the late Gerda Lerner, a UW history professor who pioneered the field of women’s history.

Clarenbach’s work with the Wisconsin commission, which served as a blueprint for feminist activism, and her UW affiliation led to her election as NOW’s first board chair.

When the group formed in 1966, NOW’s president, Betty Friedan, was already famous for The Feminine Mystique, the book that made waves for dispelling the notion that all women were happy to live lives as homemakers. Clarenbach admired Friedan’s ideas and her sharp intellect, but their partnership got off to a rough start. Clarenbach was cool headed; Friedan was not. “Friedan had moxie, but no practical skills to organize a broadly based political movement,” wrote Ellen Chesler in a New York Times essay published several months after Clarenbach’s death in 1994. Clarenbach “became the organization’s most trustworthy doer.”

In her oral history, Clarenbach did not mince words: “Betty had never organized a thing in her life.”

Although it took time for the two to “work out a harmonious and trusting relationship,” Clarenbach said, they forged a strong bond and an effective partnership. During a 1988 dinner in Wisconsin honoring Clarenbach, Friedan said, “I love that woman. It was wonderful to be in the harness with her in those early years. They might have been the best years of our life.”

From the mid-1960s to the 1970s, Clarenbach pushed for changes to Wisconsin’s state laws governing divorce, marital property, and sexual assault, and those new laws became models for the rest of the country. She was also the founding chair of the National Women’s Political Caucus, a group focused on electing women to office. She served as executive director of the International Women’s Year Commission and was the driving force behind planning the National Women’s Conference in Houston in 1977.

Billed as a constitutional convention for women, the Houston conference was a feat of organization. Clarenbach helped with 56 state and territorial meetings leading up to the event, which 20,000 people attended. A national plan of action, drafted by 2,000 delegates, asked for federal involvement to remove barriers in 26 areas, including child care, education, and health. Steinem later wrote that the conference was so pivotal that “figuring out the date of any other event now means remembering, was it before or after Houston?”

Clarenbach said Houston offered proof that the women’s movement was “not a fad and is not a creation of Ms. magazine or a couple of kooks at NOW, but it is, in fact, a worldwide movement.”

During the conference, major feminist leaders including Steinem, Friedan, and Congresswoman Bella Abzug stood on stage alongside Coretta Scott King and First Ladies Rosalynn Carter, Betty Ford, and Lady Bird Johnson. Clarenbach isn’t in any of those photos, but without her, it’s likely none of them would be.

Jenny Price ’96 is co-editor of On Wisconsin

Published in the Fall 2016 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.