The Godmother of Goat Cheese

When Anne Topham gave up academia to make the perfect chèvre, she had no idea that a herd of other artisans would follow in her footsteps.

Anne Topham ’63, MA’65 did not set out to become the Midwest’s godmother of goat cheese, but she has earned the title. Hailed by the New York Times as Wisconsin’s grande dame of chèvre, a soft goat cheese originating in France, she is acclaimed by foodies far and wide for helping launch the area’s artisanal cheese upsurge.

In the beginning, Topham’s ambi-tions lay elsewhere. In the seventies, she was a UW grad student pursuing a doctorate in the history of education. But she took a break from her research to help her father with spring planting in the rolling hills of western Iowa.

“I went from the seventeenth floor of Van Hise to watching cows calve in the pasture and learning how to disc [plow] a field. I never went back,” says Topham. “Living this close to the most elemental parts of life keeps things in perspective for me in a way that – as much as I love the stacks – the library didn’t.”

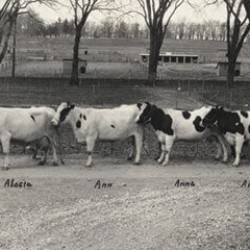

When her father saw how much she loved rural life, he remarked, “You know, you could get a goat for money, marbles, or chalk,” and the prospect struck her as irresistible. Her first dairy goat, Angelica, whom Topham describes with a wry smile as far from angelic, came with a comic three-week-old kid that Topham named after Gilda Radner. Topham sees each addition to the milking herd she now owns as a distinct character and names her accordingly after an appropriate performer, goddess, NPR news broadcaster, or politician. There will likely be a Hillary frolicking among this season’s kids.

Topham’s father coached her on the finer points of hand milking, and her quest for the best use of the pure, white goat milk was on. Topham wanted to re-create the first goat cheese she had ever tasted, a confection that had been carried from Paris to Madison by the mother of a college friend. “It was a lovely, blooming-rind round of cheese resting on a bed of straw, and I’ve never forgotten it,” she says.

As Angelica grazed on the rich hay produced by Iowa’s deep, loamy soil that summer, a brutal heat blew across the plains, pushing the mercury past one hundred degrees. Although the result was a pleasant-tasting cheese, it looked and chewed like a hockey puck – far from the creamy texture that Topham envisioned. She decided that creating an authentic French-style farmstead cheese might require grazing her goats on a rustic farmstead in more rugged terrain.

She found just that in 1982 in the Driftless Area in southwestern Wisconsin and took Angie and Gilda to forage on forty-eight acres of its craggy ridges. On the spread they named Fantôme Farm, Topham and her partner, Judy Borree ’66, MS’68, built a goat shelter out of boards reclaimed from a barn leveled by a tornado. Topham expanded her herd, added a milk house to the barn, remodeled her simple home’s attached garage into a licensed dairy plant, and continued to experiment.

Her breakthrough came when friends in Paris sent a book about making farmstead cheese. “I could read enough French to translate the book, except for the technical terms,” says Topham. She took her French text and research techniques to campus, turning to the Steenbock Memorial Library for help with French farming jargon.

Topham calls her method a blend of art and science, and she likens her quest for mouthwatering cheese to original research. “It’s about not having the answer to start with and figuring out how to get information. The deeper you get into anything, whether it’s history or cheese, the more you realize how complex every topic is,” she says. “I never think that I know everything there is to know about cheesemaking. Every day, I’ve learned something new. ”

Twenty-five years ago, Topham was one of only a few people in the United States willing to bet the farm on artisan goat cheese. “It’s only when you look back that you can see we were part of a movement,” she says. “In the early years, I felt that what I brought to the [Dane County] Farmers’ Market might be the first goat cheese that people ever tasted.

If they had a bad experience, not only would they not buy our cheese again, but they would never eat goat cheese again.”

Wisconsin now boasts nine farmstead, artisan, and specialty plants dedicated to making goat cheese. “Anne is a trailblazer,” says Norm Monsen ’80, senior market development specialist for the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection. “Anne started making these incredible cheeses, and now Wisconsin is changing from being the state that produces the most milk to the state known for great, unique cheeses.”

In 2003, Topham was the first Wisconsin cheesemaker sent abroad to study by UW-Madison’s Babcock Institute for International Dairy Research and Development. At last she was able to visit France and the goat cheese farmsteads she had imagined for so long. The report she produced from that trip, says Monsen, “really set the bar for future researchers.”

Topham continues to set the bar for artisan goat cheese. She keeps her milking herd small, only a dozen goats, and lavishes each with personal care, staying up all night to shepherd a young goat through a difficult labor or indulging her bearded mothers-to-be in their preference for tangy delicacies such as burdock shoots and freshly budded branches that she gathers on her rocky slope.

“People said, ‘What are you going to do when Chicago discovers you?’ That didn’t take very long,” Topham remembers. “But I just said, ‘There is only ever going to be so much of my cheese. I never want to get so big that I lose contact with the goats.’ ”

Though Topham’s award-winning cheese – with its silky texture and satisfying tartness – is limited, her readiness to share what she has learned with other cheesemakers is not. “Anne has been extremely generous with her time and talent [by] mentoring several of the state’s up-and-coming farmstead cheesemakers,” says Jeanne Carpenter, executive director of Wisconsin Cheese Originals, an organization that promotes artisan cheesemaking.

“Anne is always open and willing to share both the obstacles and joys of being a cheesemaker and milking goats,” agrees Monsen. “In 2006, Anne was one of the first people honored by the Dairy Business Innovation Center [a nonprofit that promotes specialty cheese and dairy businesses] for being a true innovator in the dairy industry. It was a long overdue award for Anne.” n

Denise Thornton ’82, MA’08 writes about food, health, and the environment. She is the author of a young-adult nonfiction book.

Published in the Summer 2009 issue

Comments

sue moser October 11, 2011

love this story, thank God for goats and the people that make goat cheese. I have a severe allergy to reg. ‘cow’ dairy, it is so nice th have cheese to eat, sue