The Analyst

As data mastery grows more important, politicians turn to number-crunchers such as Elan Kriegel.

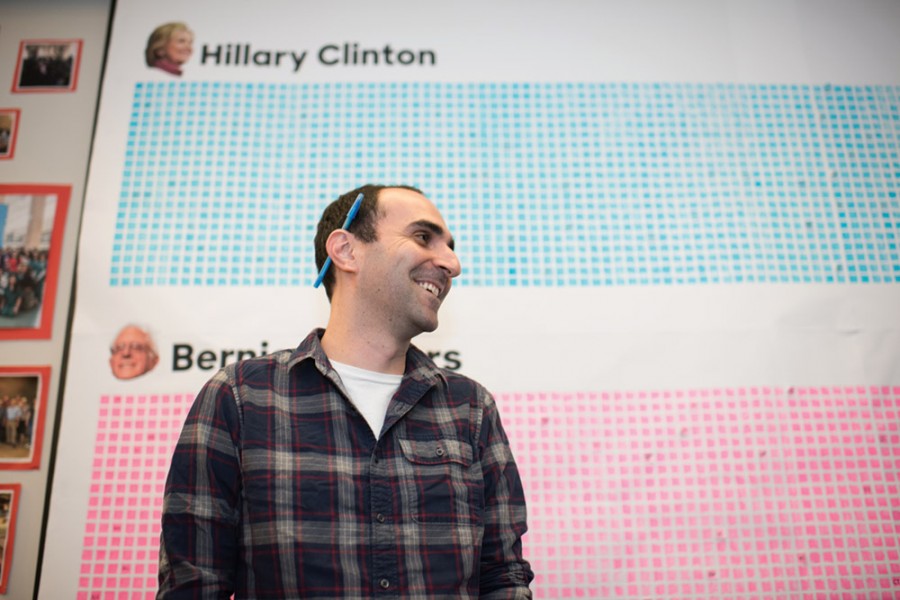

Elan Kriegel ’03 counts. In the 2016 presidential election, he may count more than anyone else.

This isn’t metaphorical. It’s not to say that he’s more important than anyone else. Kriegel is, in his way, a person of consequence, but in the election, there are many people of greater importance than he: the candidates, for instance, or leading party politicians, or major donors.

But in a literal sense, Kriegel counts. He adds and subtracts. He totals up sums. As cofounder of the data-analytics firm BlueLabs, he counts up people, places, and things, and then he tries to make sense of all those numbers. BlueLabs launched in 2013, and as the name suggests, it’s devoted to serving “blue” causes — that is, ones favored by the Democratic Party.

In 2016, BlueLabs’ chief cause is Hillary Clinton, and Kriegel is the chief data analyst for her presidential campaign. The major candidates are taking divergent courses in this election cycle. Hillary Clinton’s team is deeply involved in data analytics; Donald Trump has expressed disdain for it. “I’ve always felt it was overrated,” he told the Associated Press. “Obama [himself] got the votes much more so than his data-processing machine. And I think the same is true with me.”

Trump tweets; Clinton runs the numbers. As Clinton’s head counter, Kriegel lives at a rapid pace these days. When he talks, the words gush out, one sentence beginning before the previous sentence has finished.

Back in early April, after Clinton lost the Wisconsin primary to Bernie Sanders, Kriegel’s time wasn’t easy to come by. He had to postpone our first attempt at a conversation, and then he was running 10 minutes late for the next.

“I’m sorry about my late rescheduling and — well, I’m sorry about being late,” he said. “It’s, well, I’m embedded on the Clinton campaign right now in the Brooklyn — well, I occasionally get moved around for stuff.”

The demands on Kriegel are high because the demands for data are high: this is the age of the math geek.

“We’re in the business of predicting behavior, predicting what will happen,” says Kriegel. “But we care about the battle. We want to impact behaviors.”

• • •

Data and politics are hardly a new marriage. George Gallup came to fame 80 years ago, when his statistically tested polling methods correctly predicted Franklin Roosevelt’s re-election. And the term gerrymandering — the one that refers to drawing electoral districts to collect the most favorable body of voters? That’s essentially a data exercise. And it originated with Elbridge Gerry, who was governor of Massachusetts in 1812.

But today, there are many more data available than before, and the increasing power of computer processing gives analysts new ways to tease trends out of that information.

“In a political campaign, there are three major things you’re trying to do,” Kriegel says. “You can register people to vote. You can convince people to vote with you. And you can turn people out.”

As director of data analytics, Kriegel’s job is to figure out which people can be convinced to change a behavior to the campaign’s advantage: which unregistered voters might sign up, which might go to the polls on election day, which undecideds might come down on his campaign’s side.

“We can do a lot with data,” Kriegel says, “from predicting what’s going to happen to figuring out which voters to talk to and being a lot more efficient with our program.”

"We’re in the business of predicting behavior, predicting what will happen. But we care about the battle. We want to impact behaviors."

• • •

Kriegel’s interest in the intersection of numbers and human behavior began when he transferred from Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to UW–Madison. Tiny F&M, with only 2,300 students and fewer than 200 faculty, offered him one kind of opportunity — he was able to play football for its NCAA Division III team. But it didn’t give him the academic breadth he was looking for. He’d need to go to a larger school for that. And his mother directed him to the UW.

“I grew up in Los Angeles,” he says. “My parents are from Israel, and for whatever reason, my mother held the UW in high regard. When I was a kid, my parents talked about the UC schools and Stanford and Harvard and Wisconsin.”

He majored in math and anthropology, combining a love of numbers with a curiosity about human interaction. While on campus, he worked at Pizza Hut and at the radio stations WIBA and WTLX. In his free time, he volunteered on local political campaigns, including an effort in 2003 to raise Madison’s minimum wage to $7.75.

“I spent a lot of time helping out, just knocking on doors,” he says. “And that got me interested in thinking about why I was knocking on this door and not that one, or why was I knocking on every door, and was that a good idea?”

Kriegel’s interest in math took him to graduate school at Columbia University, where he studied quantitative methods. And when he earned his master’s, he returned to political action, taking a job at the Democractic National Committee.

“They had just opened up a data shop,” Kriegel says. “I mean, they had a data shop before, but they didn’t really know what they could do with data.”

In 2010, he worked on races around the country, and he and the party began to dig into the power of information — though it didn’t much help. That year, the Democrats lost 63 seats in the House and six in the Senate.

“So 2010 wasn’t a great year for Democrats,” Kriegel says. “But we learned that we can do a lot with data. And President Obama saw the value of this, and he wanted to make it a part of his campaign in 2012.”

It was with the Obama campaign that Kriegel began working with the crew that would form BlueLabs. Kriegel and other analysts used surveys to figure out what kinds of voters were open to changing their minds and how they might be persuaded. The data analysis team then created a model to predict how to reach those voters.

One area Obama’s data crew looked at was improving the reach of television advertising, comparing voter demographics with information about viewing habits. The result was what Kriegel calls a persuadable index, a list of television programs based on how much reach they had for voters to whom the campaign wanted to speak. And the persuadable index suggested that the campaign should look at late-night programming on children’s-oriented cable networks.

“We were able to figure out ratings from people who we thought were most likely to be persuaded by our ads and then concentrate our ads on those programs,” Kriegel says. “One of the things that came out of that is that we were advertising on Nick at Nite, which campaigns traditionally wouldn’t have done. But we saw that those shows were relatively cheap ways to reach persuadable voters.”

As the 2012 campaign built toward its conclusion, Kriegel and several of his colleagues began to talk about what would come next. They decided that they could take the work they’d been doing for the Obama campaign and use it to help a wide variety of clients. In the spring of 2013, they launched BlueLabs.

• • •

“When you’re working on a billion-dollar campaign, one of the things is, you have a billion dollars,” says Kriegel. “If you’re slightly inefficient, it’s no big deal. But if you only have $100,000, you’re going to be especially concerned about how money is spent. Those are conversations we were having all the time.”

The importance of data analysis to politics comes when a campaign realizes that its resources aren’t unlimited. It can’t do everything — it can’t advertise everywhere, it can’t knock on every door, it can’t be everyplace at once. Campaigns want to make sure that they’re putting their resources to use where they’ll make the most difference.

“How much mail should we send? Where should we allocate organizers or staff? And then there’s only one candidate,” Kriegel says. “That’s our most precious resource of all.”

Though the Clinton campaign is counting on BlueLabs to help it secure the presidency this year, that race is hardly the company’s only interest. In the three years since the company launched, BlueLabs’ crew has helped candidates in state races — such as Virginia governor Terry McAuliffe and New Jersey senator Cory Booker — as well as Fortune 100 companies and nonprofit clients, such as the Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers.

“We wanted to see if what was done for a presidential race could be done at a smaller level,” Kriegel says, “for a governor or state senator or mayor, someone running for those things. Could it be done for a not-for-profit in a small community?”

This became the motivating idea for BlueLabs. There were political campaigns, of course, but what could data analysis do for social causes?

The work is not, Kriegel admits, the most profitable endeavor, but then profit is not BlueLabs’ highest motivator.

“If we were driven by who pays the most, then that would mean that we’re not able to take a lot of the clients we believe in,” Kriegel says. “We choose industries or organizations that people in our company are interested in working on. We find that there’s so much work out there, there’s so much work we can do, and people will do even better work for some of these organizations that they’re passionate about.”

• • •

A door opens, and muffled voices call for Kriegel. He’s needed, again, as the Clinton campaign is only four days from the New York primary. She’ll win that race by 16 percentage points and go on to clinch the Democratic nomination.

After Election Day, Kriegel and BlueLabs will move on and look for the next cause it can help with better data analysis.

“Working on campaigns is so hard,” Kriegel says. “They’re so taxing, and they take so much out of you. But at the same time, the people you’re working with — they’re so smart and creative and passionate about what they do. You don’t want it to end. I mean, you want it to be over because you want to win. But that culture — you want to maintain it. You want to keep working with those people, and you want to work on causes you believe in.”

John Allen is associate publisher for On Wisconsin.

Published in the Fall 2016 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.