Science Faction

Wisconsin’s longest-serving governor recounts his support for the UW and for biotechnology research

Excerpted and adapted from Tommy: My Journey of a Lifetime by Tommy Thompson and Doug Moe ’79. Reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. ©2018 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved.

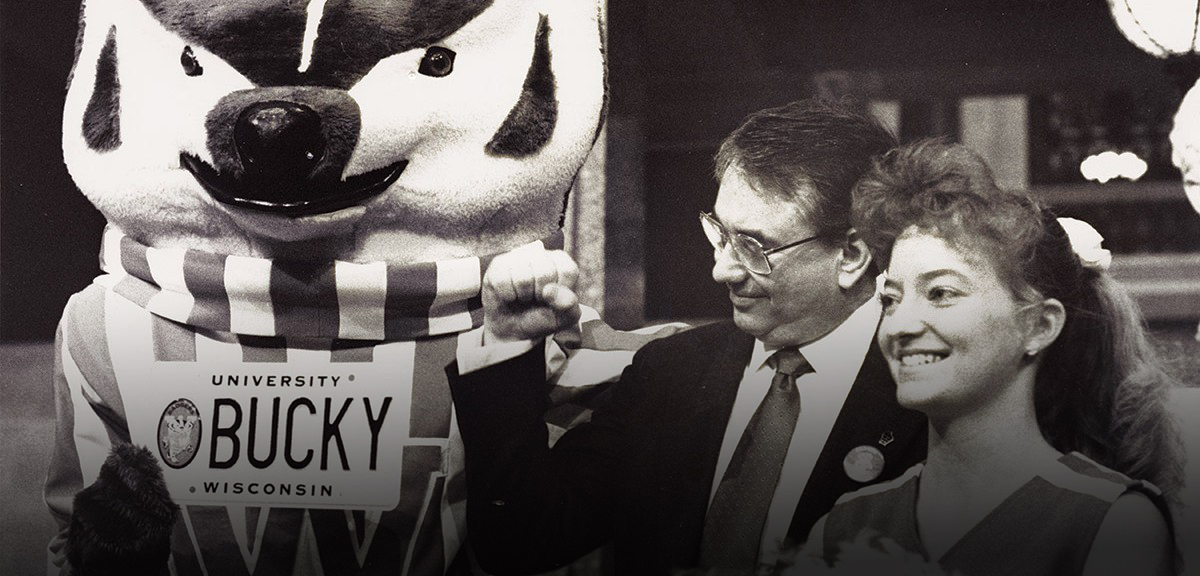

In his autobiography, Tommy, which is out this September, Tommy Thompson ’63, JD’66 shares stories about his small-town upbringing in Elroy, Wisconsin, his days on campus, and his career in government. Thompson devotes a significant passage to his support for stem cell research, both on campus and worldwide. In May 2017, the university opened the Tommy G. Thompson Center on Public Leadership, which states that it seeks to provide “a multidisciplinary, nonpartisan environment to study, discuss, and improve leadership.” Although some have questioned whether the center will live up to its nonpartisan charge, few would disagree that its namesake is known for reaching across the aisle and for being a tireless promoter of Wisconsin and its state university.

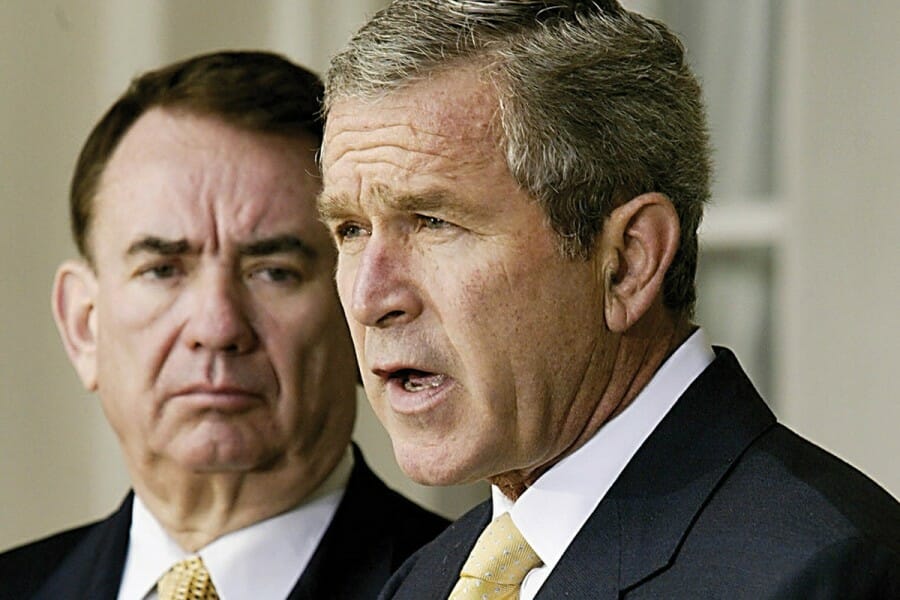

It was at a cabinet meeting that first spring after being named secretary of Health and Human Services when President George W. Bush asked me if I would stay afterward.

“I need to address stem cells,” the president said. “I want to know more about them.”

I nodded.

“I know you are for the research,” the president continued, “and I know Karl Rove [then White House deputy chief of staff] is against it. I am going to schedule a lunch for the three of us. I want you to come in, and I want you and Karl to discuss it.”

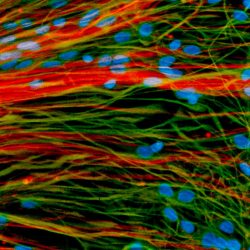

I wasn’t surprised. In my 1999 State of the State speech, I introduced James Thomson, a UW–Madison developmental biologist whose lab, in 1998, was the first to isolate stem cells from human embryos. His findings were published in Science magazine in November 1998, and the following month the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) received a patent on the discovery. Even in those early days it was being touted as a breakthrough that could revolutionize modern medicine and health care.

But the research was not without controversy. Though the cells Thomson used were left over from fertility clinics — and the donors had signed off on their use in research — some right-to-life people called it immoral, unethical, or both. They were furious with me for introducing Thomson during my State of the State speech, and it was brought up again by the Bush team prior to my appointment.

“I support stem cells,” I told them. “If that means I can’t get the appointment, so be it.”

My passionate support of Thomson and WARF were part of my larger belief that the University of Wisconsin’s emergence as a leader in biotechnology and biomedical research was great for both our state and humanity in general. Where are lifesaving advances going to come from, if not great institutions like the University of Wisconsin?

As governor, I tried to forge a partnership that would help the UW System grow while at the same time generating new technologies and businesses to pump up the state’s economy. During my time as governor, more than 4,000 building projects at a collective cost of nearly $2 billion were initiated at campuses across the state. It was a mix of public and private money. I helped Donna Shalala, before she left the UW–Madison’s chancellor job to join the Clinton administration, generate private funds to advance the expansion. Later, I called it the New Wisconsin Idea — a collaboration between academia and the private sector that would benefit both and bring good-paying new jobs to Wisconsin.

I can’t understand why any public official wouldn’t see the University of Wisconsin System as an ally, especially in a world that is changing faster than ever.

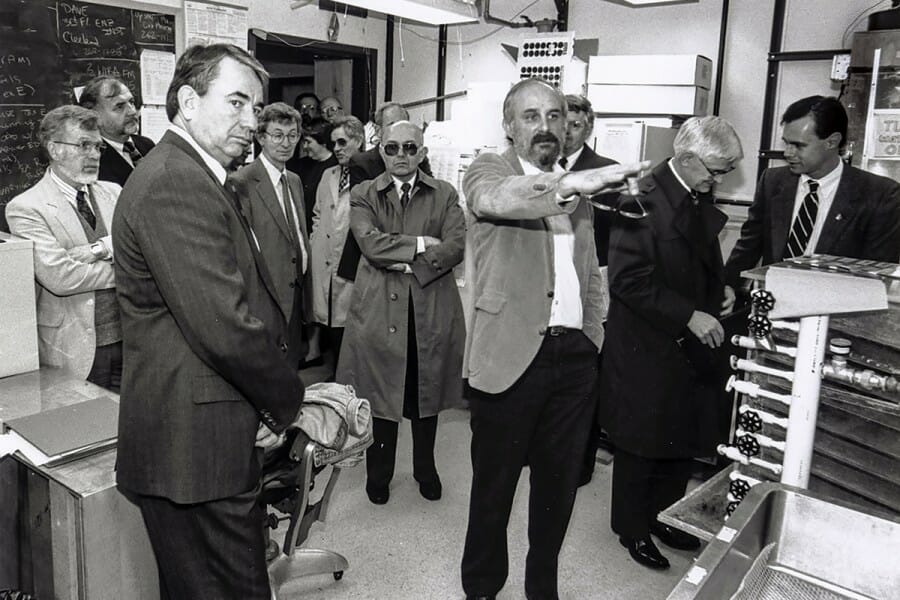

I remember having a discussion at some point in my last term as governor with John Wiley MS’65, PhD’68, who would later be UW–Madison chancellor but at the time was provost. John said he wanted me to meet Michael Sussman, a biochemist on campus who was doing some interesting work perfecting DNA chips utilized in identifying genetic abnormalities that can eventually lead to new drugs and ways to fight disease.

I said I’d be happy to meet Sussman. During my first term as governor, Chancellor Shalala had approached me about assisting with a new Biotechnology Center on the Madison campus. I agreed to help, and with a mix of federal, state, and private dollars, the center was built on the site of the old Wisconsin High School.

By the time Wiley brought Sussman to see me in the late 1990s, the biosciences were exploding on campus, and the center I’d helped fund was already inadequate. Sussman sat in my office in the capitol and for two hours talked about DNA and the potential for all this great science to generate medical advances. I liked Sussman, his enthusiasm and genuineness, though we joked later about how he’s a Democrat from New York and would never have voted for me prior to meeting me. He said that more brilliant students than ever were interested in studying biology at Wisconsin, but because of space limitations, some had to be turned away. He said we weren’t losing them to Michigan State — we were losing them to Harvard and Stanford. We’re a great university, he said, but we need a new building and more lab space.

He impressed me. Within a few days of the meeting, I called Wiley and promised funding for one of the things we had talked about: five new faculty hires in the area of human genomics. I toured the existing facilities, learning more about the science all the time. Then, in my January 2000 State of the State speech, I unveiled the $317 million BioStar Initiative, which included an addition to the Biotechnology Center as well as renovations and additional buildings for biology-related departments.

I’m proud of what I was able to do for the University of Wisconsin. It made sense for all kinds of reasons, including economic development. I was always trying to figure out how to help Wisconsin compete with the technology triangle in North Carolina and Silicon Valley. I wanted Wisconsin to be the third pillar out there.

At some point after I left for Washington and Health and Human Services, word reached me that Mike Sussman was thinking of leaving UW–Madison. He had a very attractive offer from the University of California–Davis, and was considering it to the point he’d already looked at houses.

I telephoned Mike one night from Washington — he later joked that he’d had a couple of drinks by the time I called — and asked if it was true.

“You’re thinking about leaving?”

“Yes,” Mike said.

“You can’t do it,” I said. I talked about all we’d accomplished and all that was still to come. This was when Mike confessed he was a Democrat. “I usually bat for the other team,” was the way he put it.

“I suspected it but never held it against you,” I said. We laughed. “Now, let’s talk about why you’re going to stay.”

I’m sure all my work on behalf of biomedical research at the University of Wisconsin was somewhere in my mind when I went to the White House in spring 2001 to meet with Bush and Rove to discuss stem cells.

The president had us in to the Oval Office. There’s a little room off to the side of the Oval Office, and that’s where we sat for lunch. I had a hamburger, and the president had a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

I don’t remember what Rove had to eat, but he spoke first, and he was adamant that Bush keep a hard line against allowing the use of federal funds for embryonic stem cell research. He brought up the ethical concerns, but he stressed — and this was not atypical for Rove — the potential political fallout of softening that stance. I must admit I could relate. As I noted earlier, antiabortion groups in Wisconsin were furious with my support of Thomson’s research. They are passionate, and they are vocal.

But as I have also stated, I believed that in the end, the lifesaving potential of the research should carry the day.

A few weeks before my lunch with Rove and Bush, I’d been visited in Washington by Jere Fluno ’63, a classmate of mine at UW–Madison who went on to a vastly successful career in business. Jere was also a philanthropist. I attended the luncheon in 1997 at the Madison Club when Jere’s gift of $3 million to UW–Madison for an executive education facility — now called the Fluno Center — was announced.

Four years later, he was in my office at HHS in Washington to talk to me about his granddaughter, Lauren, who has juvenile diabetes. Jere told me about getting the phone call from his daughter informing him about Lauren’s diagnosis. She was two years old. He talked about seeing that tiny girl in that big hospital bed. And he talked about the need for research to find a cure.

“Stem cells give us hope,” Jere said.

It was an emotional meeting, and I remembered it at that Oval Office lunch, after Rove had finished and it was my turn to speak. I gave myself a quick, internal pep talk, knowing that the next few minutes might be my only chance to make my case.

“Mr. President,” I said, “your mother and father have been great champions in the fight against cancer. They’ve devoted a tremendous amount of time, money, and effort to that cause.

“And you’ve started out your presidency by increasing funding for the National Institutes of Health. I thank you for that. It’s the right thing to do, a great use of federal dollars.

“But Mr. President,” I continued, “if you come out against embryonic stem cell research, no matter if you double the money for NIH, or anything else, if you turn down embryonic stem cells you’re going to be remembered as the president who was antiscience.” The president kept looking at me but didn’t say anything, so I went on.

“Every person in your administration has either a member of their family or a close friend who is suffering from a debilitating illness. You had a sister who died young of a terrible illness. Your mother and father did everything they could for that child.”

I was referencing the daughter George H. W. and Barbara Bush lost to leukemia before she was four years old.

“Every parent,” I told the president, “who has a child with juvenile diabetes, and who has to get up every night, four or five or six times, to check that child’s blood, not knowing if that child is going to live or die, those parents are counting on stem cells to come up with a cure. If you, as president, stand in the way of giving those parents the hope and dream of a cure, you’re going to be viewed as antiscience and stopping the great progress being made on juvenile diabetes, ALS, Parkinson’s — you name it.”

“But we don’t know that it will work,” the president said.

“It’s the hope, Mr. President,” I said. “The belief. And the dream.”

About six weeks later, on August 8, I was called to the White House for an early evening meeting. The president told me he was going to give a prime-time address — the first of his presidency — the following night to state his position on federal funding of research using human embryonic stem cells. The president had decided to allow federal funds to be used for research on existing stem cell lines — cells derived prior to August 9, 2001. Federal dollars would not be used for any cell lines derived after that date. It was, essentially, a compromise, and while it didn’t go as far as I might have hoped, I was pleased that the president at least went halfway. It got the federal funds flowing. I think what I said that day at lunch may have swayed him. The president didn’t tell me so, but that’s what I believe.

That night I called Carl Gulbrandsen, then managing director of WARF, which held the patent on Thomson’s research, to tell him what was coming. Carl was at dinner with his wife, Mary, in Colorado. I asked Carl, “Can you make these cell lines available?”

“Absolutely,” he said. “We’ll do everything we can.”

By the first week of September, we had signed an agreement with the WiCell Research Institute, a nonprofit subsidiary of WARF, granting NIH scientists access to the cell lines, along with academic researchers, while also respecting WARF’s patent and license rights.

There is no question in my mind that my coming from Wisconsin and personally knowing people like Michael Sussman, Jamie Thomson, and Carl Gulbrandsen helped us accomplish more in a shorter time frame than would otherwise have been the case. We respected and trusted each other. Carl came to Washington several times during the implementation process and let me know that someone at NIH told him the agency had never moved so quickly on anything. I brought a group of 20 scientists and administrators from NIH to Madison to see where the research was happening and meet the people responsible for it.

I don’t mean to suggest any of this was easy. Throughout the debate, I was caught in the middle between the strict pro-life contingent and those — like Pennsylvania senator Arlen Specter — who wanted all restrictions on embryonic stem cell research removed.

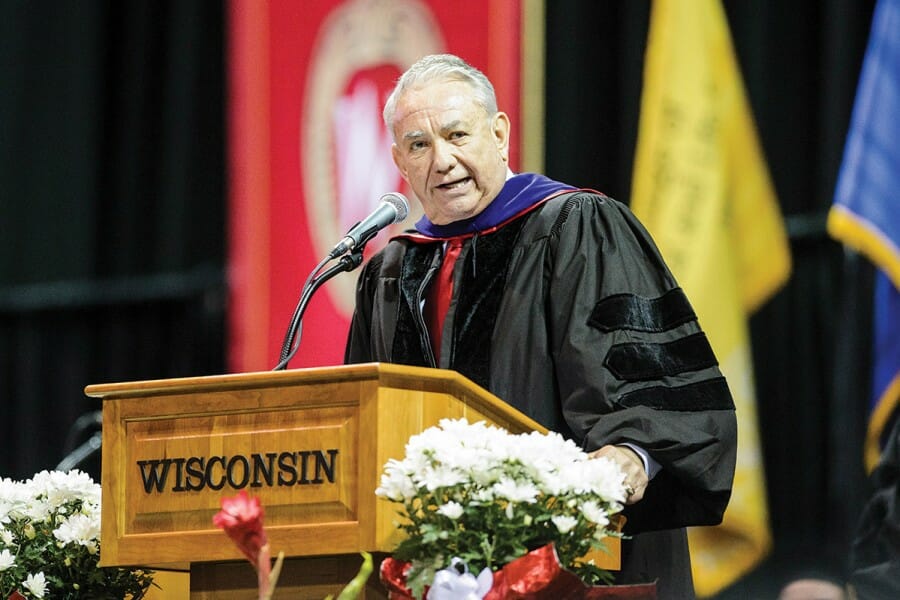

In spring 2016, UW–Madison invited me back and awarded me an honorary doctorate of laws degree for meritorious activity “as a dedicated promoter of the Wisconsin Idea and the use of government to enhance the life of its citizens.”

I spoke at commencement at the Kohl Center in Madison, and I shared the story of Mike Sussman — he stayed — while just generally touting the assets of this great economic diamond, the University of Wisconsin.

I didn’t speak long, 10 minutes or so. Primarily I wanted to thank the university for what it had given me — much more than an honorary degree — and once again make the case for how very valuable our great university is to the entire state of Wisconsin, as an economic engine and more.

I thought it was important to tell the graduating students in the audience a little about myself. How I came from a small city called Elroy, where if you dialed a wrong number on the phone you talked to whoever answered, because of course everyone knew everyone else. I talked about coming down to Madison for school with nothing but some dreams, and I told them how, with a lot of hard work, a lot of help, and a bit of luck, I’d been elected to the Wisconsin assembly and then elected governor. I’d gone to Washington and served a president in his cabinet. It still seemed so improbable, talking about it all these years later.

What I really wanted to convey was that my story, so much a Wisconsin story, could be their story, too, if they dreamt big enough and reached high enough.

Later, Chancellor Blank asked me if it would be possible to get a copy of my speech. I had to tell her there were no copies. I’d written nothing down. It came from the heart.

Published in the Fall 2018 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.