One Text Away

Parents and students are in closer contact than ever, and that bond has changed the college experience.

A mother and baby badger from the public sculpture Four Lakes, by Myklebust+SEARS, at Frances and State streets. Jeff Miller

Twenty-two. That’s not the number of favorite television episodes college students binge-watch in a week, Instagram photos they post in a day, or books they read during a given semester. That’s how often a recent study revealed they communicate with their parents during an average week.

Parents’ intimate involvement in their college students’ lives is a decidedly new phenomenon. In 2008, students and their parents averaged 13 contacts per week, according to ongoing research by Barbara Hofer, a psychology professor at Middlebury College. As recently as two decades ago, that number was typically one, often in the form of a costly, long-distance phone call on Sunday night.

By the time they get to campus, students have begun to view parents as their most trusted advocates and advisers. “The thing I’ve noticed more than the parents changing is the students changing,” says Wren Singer ’93, MS’95, PhD’01, director of undergraduate advising at UW–Madison. “Twenty years ago, the general observation I would have is that the parents wanted to be involved, but the students were kind of embarrassed. … Now students think of their parents as their best friends.”

Universities have recognized this special relationship and stepped in to help parents and students navigate the transition to college. At the UW, the nationally recognized Parent Program serves as a proactive messenger, helping parents understand what defines appropriate involvement. The program encourages parents to embrace their new role as mentors and coaches by pointing students toward resources readily available on campus to help them succeed.

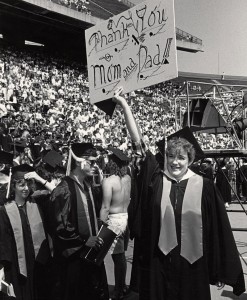

Parents of previous generations of college students (left) were mostly hands off, but today’s students “think of parents as their best friends,” says Wren Singer, the UW’s director of undergraduate advising. UW Archives S12222

The rise and fall of in loco parentis

The evolving relationship among U.S. universities, parents, and students began in colonial America. Born out of English common law in the 18th and 19th centuries, the doctrine of in loco parentis, or “in the place of a parent,” took root early at all levels of American education. Educators sought and secured the legal responsibility to preside over students (and initially, permission to administer corporal punishment). Parents expected and empowered universities to oversee and restrict students’ personal lives.

The UW was no exception. In 1927, the university hosted a “Mothers’ Week End,” inviting mothers to campus for women’s track and field events, drama performances, and a banquet. In a welcome letter, President Glenn Frank nodded to the university’s parental responsibilities, concluding, “We should be unworthy of our trusteeship if your presence did not inspire us afresh to try to maintain alongside the stern discipline of the University something of a Mother’s care and concern for the enrichment and expansion of the minds and spirits of your sons and daughters.”

Although lessening in severity over time, this paternal relationship between universities and their students largely persisted until the 1960s and 1970s.

The Vietnam War changed everything.

“There was a rebellion against all kinds of things related to colleges and universities,” says Marjorie Savage, the former director of the Parent and Family Program at the University of Minnesota, who has worked with parents of college students and researched their involvement for more than 25 years. “One of them was [the argument], ‘You’re sending my college records to my parents. You’re treating me like a child, and yet I can get drafted and go to war.’ ”

As social movements converged and consumed campuses around the country, college students demanded to be viewed as adults. They wanted privacy for their college records, freedom in student conduct, and rights for disciplinary measures. And they no longer accepted universities — or, for that matter, their parents — as figures of authority. Universities had little choice but to respond with a more hands-off approach to student affairs.

This shift culminated in the 1974 Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, or FERPA, which granted students 18 years or older the right to access, review, and challenge education records, and protected such records from being released without a student’s written consent.

After two centuries, in loco parentis was no longer the norm.

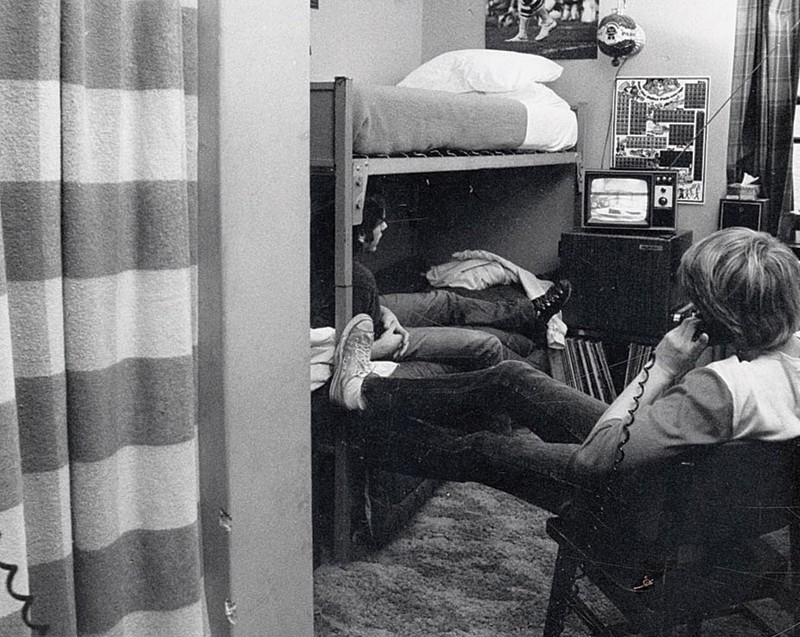

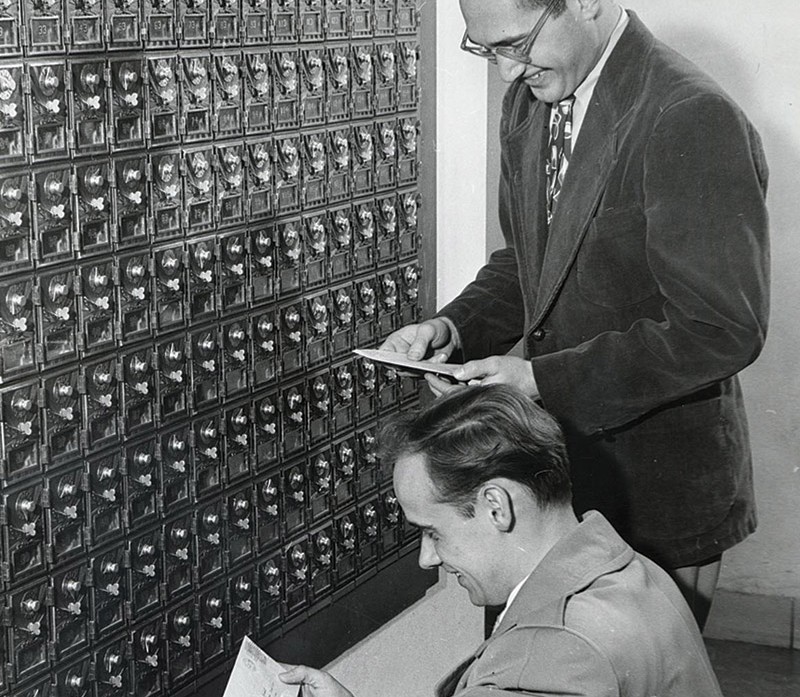

Contact between college students and their parents (this and following images) has evolved over the years from letters to weekly phone calls to daily exchanges of text messages. Bryce Richter

UW Archives S05982

Bryce Richter

UW Archives S05632

UW Archives S05651

UW Archives S07487

UW Archives S07469

Bryce Richter

55 percent

of UW parents report texting as their primary method of communication with students.

A new parental paradigm

Something peculiar happened in the decades following the Vietnam era: the same generation of students that fought for their adulthood on college campuses became the generation of “soccer moms and dads” focused on seatbelts, bike helmets, and overscheduled activities.

“It’s interesting that many of the parents who are so close to their kids — calling them all the time — are the ones who had very independent lives at the same age,” Hofer says. “[They] can’t quite make sense of it themselves sometimes, [asking], ‘Why is this so different from what I experienced with my own parents?’ ”

Julie Lythcott-Haims, former dean of freshmen at Stanford University, argues that the baby-boomer generation upended the very nature of parenting. In her book How to Raise an Adult: Break Free of the Overparenting Trap and Prepare Your Kid for Success, she identifies a number of societal shifts in the 1980s, starting with a sudden fixation on safety. Faces of missing children were plastered on milk cartons, while the 24–7 news cycle and shows such as America’s Most Wanted sensationalized crime and drugs. “Our incessant fear of strangers was born,” she writes.

Safety concerns coincided with the “self-esteem movement” — the desire to protect children from anything negatively affecting their personhood. And with more mothers entering the workforce, scheduling day care and play dates became a priority for parents. “They then began observing play, which led to involving themselves in play,” Lythcott-Haims writes. “Leaving kids at home alone became taboo, as did allowing kids to play unsupervised.” Between 1981 and 1997, the amount of time children spent with parents increased 25 percent, according to a 2001 study at the University of Michigan.

As parents became more involved in leisure, they also became more invested in education. In 1983, academic achievement rose to the forefront of the American consciousness after the federal government published a hyperbolic report called A Nation at Risk, which asserted that America’s K–12 students were mired in mediocrity.

The proximity between parents and children in leisure and academia became the new baseline.

Texting Mom and Dad

When the first wave of students who grew up under this new parental paradigm reached campus in the 1990s, relationships drastically changed. Parents were eager to stay connected to their students.

“In the ’70s, a lot of college students were first generation,” Savage says. “Their parents had not gone to college [and] bought into the fact that when you’re 18, you’re on your own. … As parents became more educated, I think they started to see themselves when they were 18 as maybe not being as prepared as people assumed they were.”

At the same time, college students no longer interpreted their parents’ advice as an affront to their independence — and they no longer insisted on being viewed as adults. In a 1994 study by psychologist Jeffrey Arnett, who first proposed the “emerging adulthood” category for 18- to 25-year-olds, only 24 percent of college students believed they had reached adulthood.

According to the 2007 National Survey of Student Engagement, three out of four students frequently follow the advice of a parent or guardian, a far higher rate than the advice of friends or siblings. “When students are asked to give examples of real-life leaders, their parents top the list,” Savage writes in her book You’re On Your Own (But I’m Here If You Need Me): Mentoring Your Child During the College Years.

When students arrive on campus, they expect to communicate with their parents once a week, according to Hofer’s research, yet they actually do so more than three times per day — and they initiate the contact nearly as often as their parents.

While societal and parenting trends may make frequent communication desirable, technology makes it possible. Parents and students most often communicate via texting and cell phone calls, according to Hofer’s latest study — a preference also identified by a 2015 survey conducted by the UW Parent Program.

1 in 5

college students reports sending papers to their parents for proofreading, according to research by Middlebury psychology professor Barbara Hofer.

Parent programs

With college students increasingly turning to parents for advice, parents are understandably turning to universities for answers. And with soaring costs of higher education, the expectations that parents have for universities — safe campuses, significant academic support, successful job placement — are also rising.

Tuition prices more than tripled at U.S. public universities between 1988 and 2008, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. And more often than not, parents are picking up the considerable tab. Nearly two-thirds of UW parents expect their students to contribute 25 percent or less to their college expenses, the Parent Program’s survey found.

“Sometimes parents are mortgaging their house to send their kids to college — it’s an investment,” says Patti Lux-Weber, who helped launch the UW–Madison program in 2007 and later served as its director. “They’re looking for a return on their investment [and] want to make sure their students are doing well and being supported.”

Further, courts have joined parents in once again holding universities responsible for student conduct — a partial return to in loco parentis. Universities became increasingly liable for lawsuits regarding student safety (both on and off campus) in the 1980s, Savage says. Even FERPA, the landmark of student privacy and independence, has become more lenient in allowing parent access over the years.

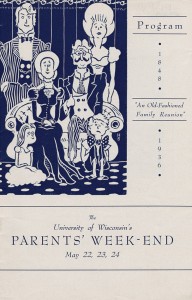

As early as 1924, the UW invited mothers and fathers to visit campus (here and below). Today, the UW’s Parent Program has 47,000 subscribers and answered nearly 2,000 parent calls, emails, and live-chat questions last year. UW Archives s17509

“Up through the 1980s, the message [to parents] was primarily, ‘You need to let go,’ ” Savage says. “In the late 1990s, we started to see parents reject that message, [thinking], ‘My kid was 17 yesterday and just turned 18 today; they didn’t suddenly become a mature and responsible adult.’ ”

UW–Madison and many of its peer institutions have been willing to answer the call — literally. In 2007, the UW launched its Parent Program, a centralized office dedicated to parent communications. Administrators were concerned that “the only time parents were actually hearing from the university is when they received a bill,” says Lux-Weber, who left the program in July.

Services began with a website, a hotline for phone calls, and a dedicated email address. Today the program has 47,000 subscribers and offers Chinese and Spanish websites, regular newsletters, a calendar and handbook, web chats, and organized campus visits. And last year it answered nearly 2,000 parent calls, emails, and live-chat questions.

The “helicopter parent” stereotype — a term popularized in the 1990s to refer to overprotective parents who hover too closely over their children and too often swoop down to intervene in moments of uncertainty — is not what guides the UW’s program.

“We don’t use the term helicopter parent,” says Nancy Sandhu ’96, MS’03, associate director of Campus and Visitor Relations, who helped found the UW’s Parent Program. “Putting labels on a group of people is just not productive. And I would say that to the contrary, if you give someone the right tools and information, it empowers them to make informed choices.”

The messages seem to be hitting home. Nearly 80 percent of parents believe their student’s experience at the UW has been or will be worth the investment, according to the program’s annual survey. Affinity is even higher, with 94 percent of parents reporting satisfaction with the university’s level of communication.

Help or harm?

The elephant in the classroom, of course, is whether significant parental involvement is ultimately helping or harming college students.

Hofer’s studies have found that students who most frequently communicate with parents are less emotionally autonomous and have lower GPAs. Savage’s work shows that having attachment to parents serves as a safety net with positive outcomes for identity development, adjustment to college, academic success, and retention. But healthy development during emerging adulthood requires both attachment and autonomy, and parents need to support both, says Hofer, who coauthored The iConnected Parent: Staying Close to Your Kids in College (and Beyond) While Letting Them Grow Up.

And the UW’s Singer, who’s also worked with first-year orientation programs, points out that much of the research and discussion around parental involvement focuses on white, middle- and upper-class parents. Studies tend to gloss over first-generation students, whose parents may not be as involved.

Ultimately, context may matter more than frequency. “If the student is calling their parent constantly and saying, ‘I don’t know what to do about this’ … and if their conversations are so lengthy that it’s taking away their engagement with the institution or their friends, I don’t think that’s good,” Savage says. “If it’s a matter of just checking in or contacting the child and saying, ‘I hope you’re having a good day,’ that’s fine. I think that’s actually healthy.”

A few years ago, Savage received a call from a disconcerted father whose son had just arrived for his freshman year at the University of Minnesota. “I hate to be a helicopter parent, but … I’m going to stay overnight tonight,” he told Savage, sheepishly. “I just have to stay this one night and then I’ll go home.”

But the father wasn’t intending to stay at his son’s dorm room and put a cramp on his son’s newfound independence; in fact, he was sitting at a hospital. His son had just broken his leg at an ROTC event on campus.

“I thought, ‘Your kid is in a strange place, a different city, knows nobody here, and he’s in the hospital,’ ” Savage says. “ ‘He needs someone with him. He needs his dad. Stay!’ ”

Preston Schmitt ’14 is an editor for University Marketing

Published in the Fall 2016 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.