Entering The Twilight Zone — via UW–Madison

Science fiction icon Rod Serling gave the university a collection of his classic scripts and stories.

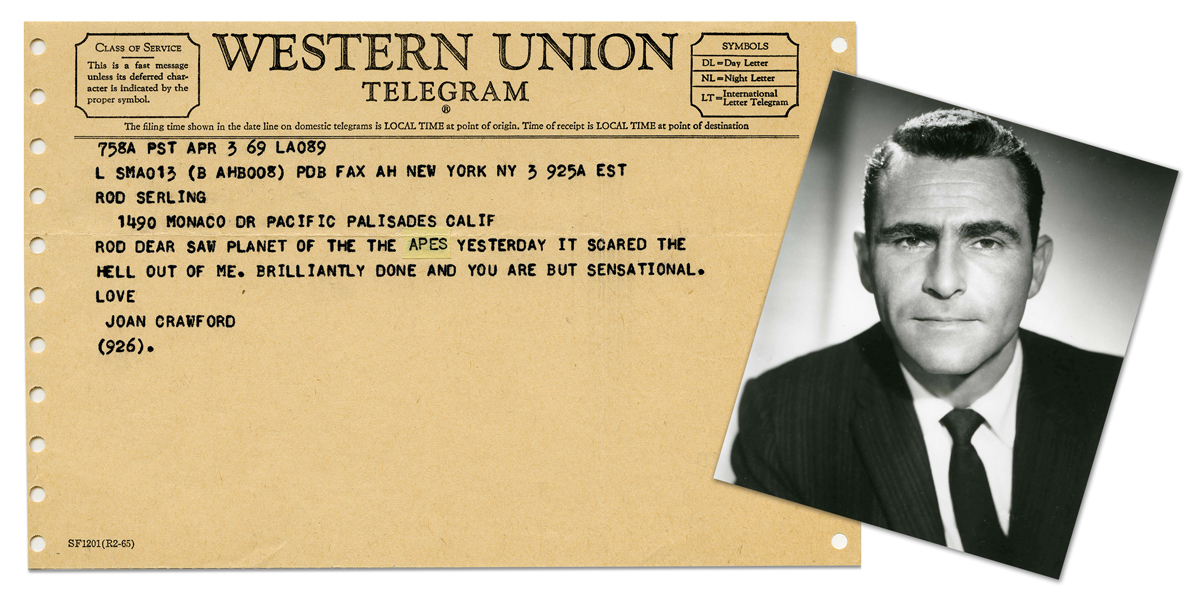

The UW’s Serling archive includes a rapturous fan letter from movie star Joan Crawford. Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research

From 1959 to 1964, Rod Serling cast a spell on TV viewers as the creator, writer, and deep-voiced host of The Twilight Zone. The science fiction anthology series ventured into “the middle ground between light and shadow,” to quote Serling’s weekly intro, intoned with an exquisite sense of foreboding. The black-and-white episodes used aliens, robots, and monsters to present eerie morality tales, addressing the social ills that troubled Serling: racism, war, conformity, cruelty.

The show’s signature device was a twist ending that drove each message home — and that, throughout decades of reruns, often sent terrified children scrambling behind the couch. That’s where I spent much of my childhood, peeking over the cushions to experience Serling’s unearthly visions in such episodes as “Eye of the Beholder” and “It’s a Good Life.”

Serling had no connection to Wisconsin but, in a Twilight Zone-style twist, donated his sizable archive to UW–Madison’s Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research in 1963. It was the result of pure hustle: then-director David Knauf boldly wrote Serling a letter to see if he would be willing to hand over documents.

“Serling liked the idea of students being able to use his collection to learn from,” says Mary Huelsbeck, the center’s current assistant director. “He responded quickly, and we were the first to have this material.”

In the archive, scholars and fans can find scripts for The Twilight Zone and other socially engaged productions that elevated the television medium in the 1950s and ’60s. There are also Serling scripts for the enduring 1968 fantasy film Planet of the Apes and the 1970s TV horror series Night Gallery — another one best viewed from behind the couch. Other material includes speeches for various good causes, a delightful fan letter from movie star Joan Crawford, and communications with TV executives nervous about Serling’s controversial ideas.

Sifting through all this stuff, Huelsbeck says, you sense “a really nice guy who could also be a tough guy when he needed to be.”

Coolest of all, the UW has 1,200 recordings of Serling dictating his scripts via old-school Dictabelt technology.

“He was busy, so he didn’t type out his scripts,” says Huelsbeck. “It’s amazing to hear how quickly Serling could think while writing these scripts in his head.”

After listening to one of the Dictabelt recordings (see below), I would have to agree. But just hearing that haunting voice again scared me silly.

Published in the Winter 2024 issue

Comments

Jeff Baker December 10, 2024

Wow! I’m a writer, Serling is one of my heroes!