Chasing the Story with David Maraniss

Here’s how the Pulitzer-winning reporter and biographer gets the scoop.

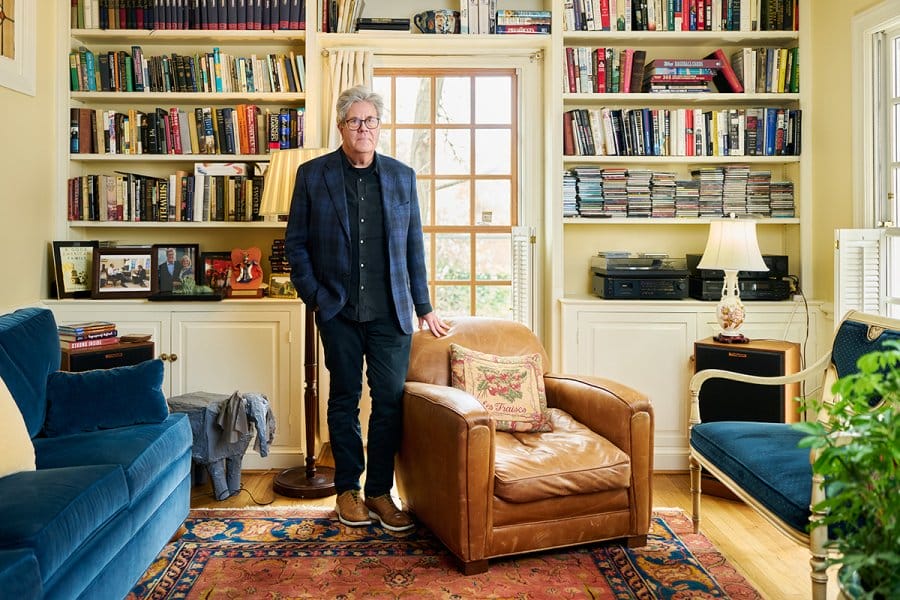

The branches of David Maraniss x’71’s family tree are weighted down with reporters, authors, editors, playwrights, and poets who embrace the family motto: “Go there — wherever there is.” That means following the story, wherever it leads.

It’s one of the secrets behind Maraniss’s career, which includes 13 books, two Pulitzer Prizes, and five decades of articles on the consequential topics of our time, most notably published in the Washington Post. Maraniss has written acclaimed biographies of Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, Roberto Clemente, Vince Lombardi, and Jim Thorpe. He has also produced three nonfiction narratives set in the 1960s: Rome 1960, on the summer Olympics; Once in a Great City, on Detroit; and They Marched into Sunlight, which parallels a 1967 Vietnam War battle and a student protest at the UW. (See sidebar.)

What does “go there — wherever there is” entail?

When researching a book on legendary Packers football coach Lombardi, Maraniss convinced his wife, Linda, to move to Green Bay, Wisconsin, to experience the minus-17-degree environs of Ice Bowl fame. There, he met Lombardi’s paper boy, golf caddy, and the piano player from his favorite supper club.

In 1991, “going there” required ditching a rental car in a tiny Oklahoma town and cajoling a pilot at a small airstrip to fly him to Norman in an open-air, two-seater plane, despite a terror of flying. The goal was to make Anita Hill’s press conference on sexual harassment allegations against then–Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas. “My need to get there in time overwhelmed all of my fears,” he says.

Though Maraniss spent only two years as a UW student, they were crucial ones in shaping his journalistic spirit.

“I attribute my entire sensibility,” he says, “to Madison and to the University of Wisconsin.”

“Ink in My Blood”

David Maraniss arrived in Madison in the summer of 1957 in a two-tone Chevy packed with his parents and three siblings, shortly before his eighth birthday. His beloved Milwaukee Braves were on their way to winning the National League pennant and the World Series, and his father, Elliott Maraniss, had secured the job that “saved our family.”

This was five years, seven cities, and three newspaper jobs after Elliott was blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee and fired from the Detroit Times — an experience recounted in David’s book A Good American Family. Elliott turned to the Capital Times, with its reputation of standing up against McCarthyism.

“I was born with ink in my blood,” David wrote for his Pulitzer profile. “My grandfather was a printer in Brooklyn, and my father spent most of his career as a newspaper editor straight out of The Front Page, with a gruff demeanor, soft heart, and instinctive sense for the news.”

Maraniss often tagged along with his dad to work. Elliott once introduced him to colleagues by saying, “He’s going to be the best writer of all of us.” That is a moment Maraniss never forgot. “It propelled me in some ways,” he says.

Maraniss needed that extra push as he struggled to figure out where he fit into the family. His younger sister, Wendy, who died in a car crash in 1997, was a brilliant classical pianist. “I had two older siblings who were pretty much geniuses, Jim and Jeannie. They went to Harvard and Swarthmore and got 1600s on their SATs, and I was the dumb kid in the family.”

The romance of the old-time newsroom in downtown Madison drew him in. “Reams of copy paper, dark blue carbons, glue pots, pneumatic tubes, thick markup pencils, cigarette butts on the linoleum floor, the [copy desk] manned by old guys in suspenders with flasks of liquor stashed in the bottom drawer,” recalls Maraniss. “That was the newspaper milieu imprinted on my brain, and I loved it.”

“The whole sensibility of the school and the Wisconsin Idea and ‘sifting and winnowing’ — it soaked into my body in a way that probably no course I could have taken would have done. I’ve been shaped by that progressive notion of academic freedom, the truth, trying to connect learning to living.”

At age 19, Maraniss began writing for his father’s paper and for the next five years worked there and at Madison’s WIBA radio. He repurposed wire service copy from the Washington Post, including the famous reporting by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein on President Richard Nixon and Watergate. His own beats were sports and student protests, topics he returned to later in his career.

Maraniss calls his UW–Madison experience “a tumultuous time,” packed with chess matches in the Rathskeller and basketball games in the Red Gym. After his sophomore year in 1969, he married his high-school sweetheart, Linda, and the next year, their son, Andrew, was born. Linda recalls sending David to the store to buy diapers; he came home with a Simon and Garfunkel album instead.

He dropped out of the UW, although in 2014 he was awarded an honorary degree and notes, “It was a disaster that turned into a wonderful thing.”

“The University of Wisconsin affected me mostly by osmosis,” explains Maraniss. “The whole sensibility of the school and the Wisconsin Idea and ‘sifting and winnowing’ — it soaked into my body in a way that probably no course I could have taken would have done. I’ve been shaped by that progressive notion of academic freedom, the truth, trying to connect learning to living.”

Maraniss, now working full time on his books, still lives in Madison for part of the year, and he calls the Memorial Union Terrace his favorite place in the world.

One-Day Masterpieces

At age 25, Maraniss headed east to the Trenton Times, and in 1977 he started at the Washington Post. His journey to becoming a legendary reporter — earning his first Pulitzer for reporting on Bill Clinton in 1993 — was not without its speed bumps. He shares a time when his reporting went sideways: his coverage of the 1976 Democratic National Convention.

“It was my first political campaign, and I was covering Jimmy Carter at my first job outside of Madison. And I wrote an opening paragraph that probably had 10 or 12 dependent clauses in it.”

“Davey,” his editor told him upon reading it, “try diving off the low board for a while.”

Those are surely not words Maraniss ever said to his own reporters. Along with distinguishing himself as a writer, he served as a Post editor, and people who’ve worked for him describe him as patient, encouraging, brilliant, and sensitive. The latter is a trait he attributes to his mother, Mary, whom he describes as a “preternaturally calm woman, not easily provoked.”

Journalist Anne Hull’s work exposing mistreatment of veterans amid the squalor at Walter Reed hospital won the Washington Post a Pulitzer Prize for Public Service in 2008. Maraniss worked with Hull on that series as her editor.

Her job as a national enterprise reporter put her on the road for months at a time. “It can be a lonely process out there,” says Hull. “What made it so great was David Maraniss. He made me feel like I had a partner in the reporting.”

She praises his ease at building the “scaffolding” of a story. They also had fun. She’d share mixtapes of music reflecting the location and themes of her reporting. When editing together, she’d join him for his routine reporter lunch of egg salad on rye toast with a V8 juice.

“He’s a gift that rarely ever happens in a newsroom,” says Hull. “He’s extremely smart, extremely well read, but you’d never know it because he doesn’t flaunt it.”

“Without being self-righteous or self-important, he shows what’s right, what’s wrong, and what are the implications. I’m not overstating it to say he’s a moral force.”

— Bob Woodward

At the Post, reporters could observe Maraniss in his glass office. Every few hours, he’d emerge in his socks and make a newsroom round, earning him a moniker from Hull: the Shaggy-Headed Shambling Shaman.

He was in that fishbowl when he composed what became known as a “Maraniss masterpiece” in just one day: a 9/11 article that is taught at journalism schools around the country. Maraniss conceived the story while sleeping, scrawled out a one-page outline, taped it above his computer screen, and began typing at 6 a.m., four days after the terrorist attacks. He produced a chronological narrative about dozens of daily routines that were forever altered by the event.

Maraniss repeated that process in 2007 as part of the team covering the Virginia Tech mass shooting. That story, also written in one day, contributed to another Pulitzer.

Due to his atypically serene newsroom demeanor, he was often the good-cop contrast to such editors as Ben Bradlee or Bob Woodward. His approach paid off when Janet Cooke insisted she had not made up her Pulitzer-winning 1980 story about an eight-year-old heroin addict. Around 1:45 a.m., after 11 hours of pressure from the team of editors, Maraniss asked the others to leave the windowless conference room.

“I knew she would not be able to lie to me,” he explains. “Without in any way approving of what she did, I understood the horror she must have been facing at the moment, being exposed as a fraud.”

Alone with Maraniss, Cooke confessed.

Today, the Pulitzers serve as paperweights on his desk. And Woodward is a golf partner, close friend, and a fan.

Maraniss’s mission is to “search for the truth and use deep reporting and common sense in its pursuit.”

“Besides being a great journalist and a great writer, he is always interested in what a story means, where it fits into the morality of people and country,” says Woodward. “Without being self-righteous or self-important, he shows what’s right, what’s wrong, and what are the implications. I’m not overstating it to say he’s a moral force.”

“I’ve Got to Do His Biography”

The morning after Clinton was elected president in 1992, Maraniss woke up in a motel outside Little Rock, Arkansas, reflecting on how well he’d come to know what made the president-elect tick over the past year.

“I’ve got to do his biography,” thought Maraniss, who has a fierce competitive streak, whether it’s getting the story or winning a game of Scrabble. “I don’t want someone else doing it.”

That began his career of writing books. His mission remained the same: “Search for the truth and use deep reporting and common sense in its pursuit.”

Last year, the Wisconsin Historical Society received proof of just how deep Maraniss’s research goes when he donated 150 boxes filled with thousands of notecards, binders, tapes, and photographs from his books.

Maraniss refuses to devote the steep commitment of time — typically three to four years — to a book unless the subject evokes a curiosity verging on obsession for him.

Whether the subject is sports or politics, his books explore racial justice — another thread he traces back to his father, who was commander of an all-Black unit in World War II.

“Clinton was a product of the segregated South, and he wanted to change that,” he says. “Vince Lombardi was very strong on race and gender issues, even as he was old school in so many other ways. Rome 1960 is about Muhammad Ali, Abebe Bikila, Wilma Rudolph, and what they had to endure. The Obama book, obviously, deals with race. Once in a Great City does, too.”

Maraniss’s current obsession is Jack Johnson, the son of a former slave and the first Black heavyweight champion boxer back in 1908. He refuses to devote the steep commitment of time — typically three to four years — to a book unless the subject evokes a curiosity verging on obsession for him.

To do so, it must illuminate the sociology and history of America. And Johnson’s life hits on all Maraniss’s pulse points: racial justice, sports, politics, and underdogs. His working title is Ghost in the House, “a reference to what Muhammad Ali’s trainer would whisper to him in the ring before every match, meaning that Jack Johnson was watching him.”

The Next Generation of Journalists

Ink as a genetic marker among the Maraniss clan has now been passed along to his two children.

His son, Andrew Maraniss, has authored four books of narrative nonfiction on sports figures tied to racial justice and underdogs. His daughter, Sarah Vander Schaaff, is a playwright and journalist whose career began at CBS News. During COVID, Maraniss did a podcast with Sarah for two years called Ink in Our Blood. His four grandchildren, who range in age from 11 to 20, are well on their way to becoming another generation of writers, from theater to poetry to sportscasting.

The Maraniss children describe their parents as “youthful.” David and Linda raised the kids as “one of the gang” with their friends.

Andrew tagged along to news conferences, met politicians, and pocketed Associated Press photos of the Milwaukee Brewers. The kids joined the Washington Post’s rotisserie baseball league, sang songs around the piano at Maraniss house parties, and played touch football every Sunday afternoon in the green grass under the Washington Monument.

“Bob Woodward was the first person who ever showed me a Walkman, and he got my sister and me some 45 records,” Andrew says. “So I grew up around these great reporters and editors, and it gave me the confidence to become a writer myself.”

“He’s very attuned to the younger generation,” Sarah says of her father. “And he’s actively engaged in the next generation of journalists.”

Indeed, Maraniss teaches classes at Vanderbilt University and views mentoring as among the most important facets of his work.

Philip Rucker is glad he feels that way.

Rucker, who was the Post’s national editor before recently making the jump to CNN, began working with Maraniss during the 2012 campaign cycle as he covered the Republican nominee, Mitt Romney.

“David taught me how covering politics is not just about the politics, the slogans, and the strategies. It’s ultimately about the people,” says Rucker.

Their roles switched when Rucker became an editor. He worked on the piece Maraniss wrote with Sally Jenkins on U.S. representative Jim Jordan ’86, not as a politician but as a wrestling champion and coach.

And how was the copy Maraniss turned in?

“David’s copy sings like nothing you’ve ever heard before,” says Rucker. “He is a masterful composer of stories.” •

Melanie Conklin MA’93 is a Wisconsin journalist and political communications director.

Published in the Summer 2025 issue

They Marched into Sunlight: War and Peace, Vietnam and America, October 1967 devotes nearly 600 pages to just two intense days. David Maraniss draws on his UW–Madison roots in his intricate stories about a Vietnam War–era campus protest against Dow Chemical Company, the manufacturer of weapons Agent Orange and napalm. Students crammed into the halls of the UW Commerce Building, the site of Dow’s job recruitment. The protesters were beaten bloody with nightsticks in the ensuing confrontation with Madison police.

They Marched into Sunlight: War and Peace, Vietnam and America, October 1967 devotes nearly 600 pages to just two intense days. David Maraniss draws on his UW–Madison roots in his intricate stories about a Vietnam War–era campus protest against Dow Chemical Company, the manufacturer of weapons Agent Orange and napalm. Students crammed into the halls of the UW Commerce Building, the site of Dow’s job recruitment. The protesters were beaten bloody with nightsticks in the ensuing confrontation with Madison police.

Comments

Nancy Merriman July 4, 2025

An eye-opening article, especially since his topics are so relatable to me, a UW grad (’65), Wisconsinite, and fellow liberal. Why have I never read Maraniss’s books? I will now.