An Exercise in Grief

A new memoir provides a loving and candid look at the author's relationship with — and sudden loss of — her father, New York Times journalist David Carr.

In All That You Leave Behind, Erin Lee Carr ’10 invites the reader to join her on an intimate journey of tragedy and triumph. As she struggles to come to grips with the 2015 death of her father and mentor, the legendary New York Times columnist and best-selling author David Carr, she highlights the inconvenient complexities that make us all human. David wrote about media and culture and published 2008’s The Night of the Gun about how he overcame a cocaine and alcohol addiction. Erin’s memoir, excerpted below, outlines her own struggle with alcohol addiction, as well as her time on campus and her blossoming career. Erin is a director and producer known for HBO documentaries such as At the Heart of Gold about the USA Gymnastics sex abuse scandal and I Love You: Now Die about the Michelle Carter murder-by-texting trial. “I’m a hard worker, and I think Madison very much instilled that in me,” she said in a UW interview in 2013. In 2018, she was named to the Forbes “30 Under 30” list of the most influential people in media.

In All That You Leave Behind, Erin Lee Carr ’10 invites the reader to join her on an intimate journey of tragedy and triumph. As she struggles to come to grips with the 2015 death of her father and mentor, the legendary New York Times columnist and best-selling author David Carr, she highlights the inconvenient complexities that make us all human. David wrote about media and culture and published 2008’s The Night of the Gun about how he overcame a cocaine and alcohol addiction. Erin’s memoir, excerpted below, outlines her own struggle with alcohol addiction, as well as her time on campus and her blossoming career. Erin is a director and producer known for HBO documentaries such as At the Heart of Gold about the USA Gymnastics sex abuse scandal and I Love You: Now Die about the Michelle Carter murder-by-texting trial. “I’m a hard worker, and I think Madison very much instilled that in me,” she said in a UW interview in 2013. In 2018, she was named to the Forbes “30 Under 30” list of the most influential people in media.

It was Thursday night, and I had work to do at my office in Brooklyn the next day, so I kissed [my boyfriend] Jasper goodbye and headed into the subway. When I got out, I had two missed calls from [my stepmom] Jill. I called her back.

“Listen to me carefully, and do not panic,” she said. “Someone called me from the Times saying that Dad has collapsed. I need for you to get to St. Luke’s Hospital. I’m in New Jersey and heading into the city right now, but you’re closer and can get there first. I called Monie and she will be there to meet you. Do not call your sisters. I want to know what the situation is before I call them.”

I hung up and looked at the subway, calculating how long it would take to get to the hospital, before realizing that was insane and quickly hailing a cab. After I closed the car door, I sat and obsessed over the lack of descriptors in Jill’s call. What did “collapsed” mean? Was he conscious? Alive? I called my best friend, Yunna. My voice cracked. She sounded startled by the news but told me everything was going to be okay.

I listened to an audiobook on my iPad (his iPad that he gave me), anticipating that I’d need to be in a semi-stable state of mind for whatever came next. I played Gretchen Rubin’s The Happiness Project and tried to stop sobbing. When I paid the fare, my cab driver mumbled, “I’m sorry.” I nodded but had no words.

Monie, a close family friend, was there waiting. As I ran to her, she said loudly to the security officer in the triage area: “This is David Carr’s daughter!” Just hours before, I had heard those words as I tried to find my seat at his event. My whole life it had been my introduction; I hoped to God that I would hear it again.

Dean Baquet, executive editor of the New York Times, walked over to me in the ER reception area. There was nothing to say except the truth: “He’s gone. I’m so, so sorry.” I heard shrieking; Monie was screaming loudly. I was mute. I noticed that Dean was wearing a purple scarf. Jill had not yet arrived.

They led Monie and me into a small waiting room where a young bearded guy was seated. Apparently he was the one who’d found my dad’s unconscious body on the floor of the Times newsroom. He had tried to do CPR but was unsuccessful. He looked down. None of us had a single thing to say. Boxes of tissues littered the top of the generic wooden coffee tables. I reached for one.

I excused myself and went to the bathroom to call Jasper. “Is he okay?”

I didn’t yell or scream the worst words I have ever said out loud. Instead, I whispered them, willing them back into my head, but there they were.

“He died.”

I threw up immediately.

“Oh my God, babe, oh my God,” Jasper said over and over.

His words rang in my ears.

I woke up the next morning certain that I was dying, too. The words “My dad is dead” beat like an awful drum inside my head. Suddenly, a memory flashed. Christmas Eve, a few weeks before. We were all sitting around the living room. My dad had made a point to celebrate how life had worked out nearly perfectly for everyone in our family. Relationships, jobs, money, happiness. I remember thinking how right he was. “Everything has broken our way,” he’d concluded.

Now everything was just broken.

No one gets to choose the traits they inherit from their parents. I was blessed with a semblance of smarts, blue eyes, and giant, man-sized feet. When I was 13, a kind, elderly pediatrician remarked that with feet like these, I was sure to grow in height. At 27 years old I’m still five feet, four inches. But other promised inheritances have come true. Some darker than others, like a fondness for the drink.

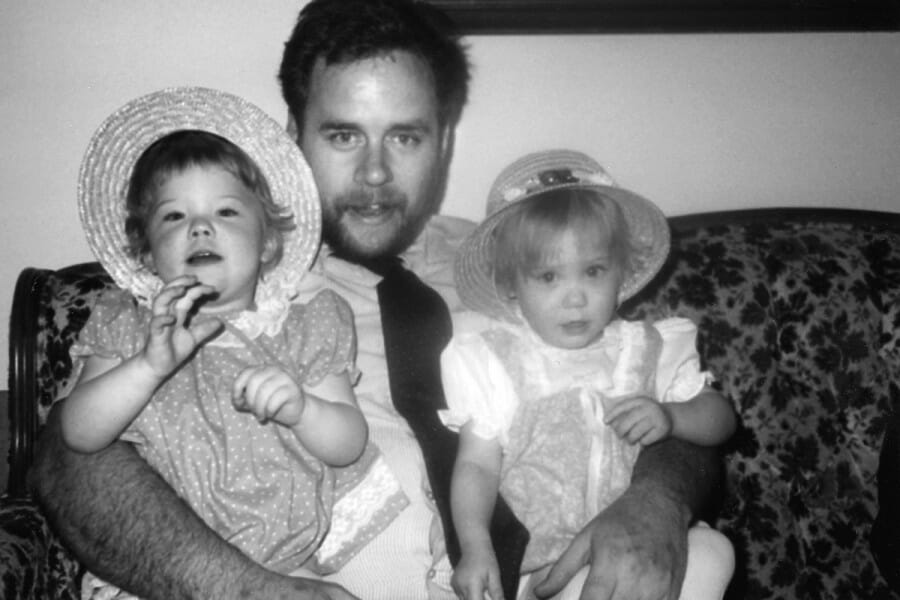

When I was growing up, my dad often whispered to my twin sister, Meagan, and me, “Everything good started with you.” I realized the converse truth — that there must’ve been an “everything bad” before there was an everything good.

When I was in third grade, living in Washington, DC, a friend came over after school one day. Let me preface this by saying this wasn’t a typical event in my life. I was an awkward kid who had no clue as to what was “cool,” and the savvy kids knew to stay the hell away from me. Finally, after many failed attempts, I made a friend. Her name was Alex.

Jill picked us up from school, and I remember Alex gave me a funny look when I called Jill by her first name, instead of “Mom,” and later asked me about it when we were alone in my room. I explained to her what had been explained to me, that my parents used to be drug addicts, but my dad no longer did drugs and was now married to Jill. You know, basic eight-year-old stuff.

It was hard for my eight-year-old brain to grasp the true dark story of what had happened, but I eventually learned that my parents’ appetite for cocaine was monstrous, quickly moving from recreational use into freebasing. No one celebrated when my mom found out she was pregnant, but the show went on. My mother claims she used only a couple of times while Meagan and I were in utero, though she is the only one who knows this for sure. After six and a half months of pregnancy, her water broke and she went into labor. It was the spring of 1988, and the math did not look good.

Our premature little bodies were placed in incubators. My dad and mom continued to use, and the relationship dissolved when the coke business was done. We were a product of the union but also a reminder that they were not good together; they split after we were born. I have been told that my dad’s moment of reckoning, as captured in his memoir, came when he left us in the dead of winter, strapped into our snowsuits in the car, to go score and get high in a nearby crack house. We could have frozen to death.

In our first year, my mom took turns taking care of us, these little babies. She had two previous kids of her own, and it was obviously a lot to handle. Once again she turned to drugs. It was clear that she was not a viable option in terms of guardianship, nor was my dad. Who was left?

In December 1988, when we were eight months old, my dad entered an inpatient rehabilitation facility whose name held a sort of reverence in our home: Eden House. My sister and I were placed temporarily in foster care through Catholic Charities. Our caretakers were Zelda and Bob, kind Minnesotans whose kids were all grown up. When my dad was writing [his memoir], The Night of the Gun, he interviewed them, and they recounted his erratic behavior. Direct, intense, falling over. He wanted us to receive perfect care, but he looked desperately unable to provide any. Zelda recalled feeling horrified and glad to scoop us up into her arms. My grandmother was with him when he dropped us off.

She didn’t have high hopes. It would be his fifth time in treatment.

After much hard work on his part, we were returned to our dad after he successfully finished his six-month program. He had the reason for recovery right there in front of him. What would happen to us if he picked up a drink or used again? I can only imagine how unmanageable it must have felt for him at times, single-parenting two babies that needed every goddamn thing from you.

We developed a life, in small, finite ways. Grocery store, walk home, dinner, bath, story, bed. A routine is what we all craved after the chaos early on. His lawyer, Barbara, asked him to keep a journal of our life together, in case the judge needed proof that he knew what he was doing. How many times he changed us, what he fed us, what bedtime looked like. While the diary started off as the ramblings of an incoherent and sleep-deprived addict in early recovery, it became the written testament of a single parent who fiercely loved his children. And we loved him back.

When I look at photos of my mom, I search for the woman my dad fell in love with. He could be violent with her, and there were things that happened during their time together that she could not forgive. She’s told me she feared for her life, but my dad said she left us with him to pursue her drug habit. He eventually filed for sole custody, citing child abandonment. There is no record of her contesting the paperwork or responding in any way. My dad became our sole guardian, a rarity back then for a father in child custody disputes.

I have not seen her since I was 14 years old.

After all the stories, with all their hints of what I’d inherited, of course I would stay away from drugs. I was smart enough to avoid repeating the same mistakes. That path had been worn out, and I was going on the straight and narrow. Or so I believed.

During the summer of my sophomore year of high school, my friend Jenny and I invited our small cohort over to watch Ryan Phillippe bamboozle the ingénue Reese Witherspoon in Cruel Intentions. Buzzed on the underlying sexual tension, we were looking for something to do next.

“I know my parents keep a bottle of vodka around here somewhere; we could take turns,” Jenny offered as she left the room in search of a bottle of lemon- flavored Ketel One. She came back with a bottle, and we traded swigs, all the while grimacing at how “gross” it tasted.

But in truth, it didn’t taste gross to me; it tasted like pure magic. My head started to hum, my smile felt easier. The night devolved into YouTube videos and fits of laughter until we all passed out. Later that night, I stole to the basement one more time to take additional swigs. I pressed the bottle to my mouth until it was empty and promptly threw up all over the basement floor. The next morning, Jenny wondered aloud why I got so sick when we only had a couple of sips. I didn’t have the courage to admit that I drank more by myself. Instinctively I knew that was something that should be kept secret.

Eventually it came time for me to pursue higher education. Almost a decade after we left the Midwest, my family and I made the drive back — this time from New Jersey to Madison, Wisconsin, where I would be attending college. We pulled up in our Ford Explorer to the dorm that would be my home for freshman year; I was sweaty from days in the car with my dad, Jill, and Meagan. I was also sweaty from nerves. Did I look the part of a hip-but-edgy college freshman? I had dyed my hair an auspicious color of fire-engine red and cut it short. I rocked a Rolling Stones T-shirt and red-and-black-striped skinny jeans from the cult-kid-wannabe chain Hot Topic. Years later, my dad teased me that it seemed like my mission was to go to college as ugly as possible.

Before he left me at the dorm, he told me to have fun but to practice caution; he knew that college would be a time of high jinks. And as always he told me how desperately proud he was of me. A couple of tears leaked out of my eyes as he hugged me. I was ready, but that didn’t mean it didn’t hurt to say goodbye.

It took a while, but I started to get the hang of the whole college thing. I logged some serious time in the library, but I also devoted quite a few hours to drinking amber liquids at the famed Wisconsin student union with my beloved gang of miscreants. I felt like I found my people in college — weirdos like me who laughed loudly and stood out among the preppie Wisconsinites that lived for football Saturdays. Sure, we went to football games, but it was mostly just used as an excuse to drink.

Once, on a night before my dad was due to arrive for one of our biannual visits, my roommate Jamie clumsily elbowed me in the face while drinking. As a result, my Monroe piercing (a stud above the lip) became infected. It. Was. Not. Pretty.

When my dad stepped off the plane the next day, he took one look at me and said, “What the f—?” Instead of dropping off his luggage at the Best Western downtown, we headed straight for the piercing place on State Street. The Monroe had to go. I protested, albeit weakly, because in truth the throbbing in my face was getting to me. Afterward, we walked outside. “What is it about you that trouble just sort of follows you around?” he asked, his expression one of bewilderment tinged with disappointment. I expected him to crack wise but was met with silence. He looked at me and said, “I have to say I am a little worried about you. … Did this happen while you were drinking?”

The question hung in the air. While my dad had been sober for most of my childhood, my mom had not. I knew what addiction looked like. The disorder ran in my genes. I tried to push that feeling to the far reaches of my brain whenever it surfaced, with moderate success, but I saw the disease infect the people in my life. Some would recover. Others, like my mother, would not. The warning was there when I took my first drink.

In college, I kept an online journal, and I typed furiously about my burgeoning drinking problem. Still, I got mostly Bs and some As. I could study and hold down a part-time job. I had a friend group that was full of smart, genuine people. I was responsible and showed up on time. But I often woke up drenched in sweat, paranoid about the things I did or said the night before, knowing I would just do it again the next weekend. Drinking, even when I was 18, started to guide my choices.

On April 15, 2008, I finally turned 21. My dad sent me a bottle of Dom Pérignon and a letter. Despite his misgivings about my drinking, he felt I deserved to enjoy some nice champagne. I never asked him why.

Sudden death creates a creeping sensation that you are living in an alternate reality. As weeks passed, I couldn’t help but text him. Because we’d been so digitally tethered, it felt only normal, albeit a bit morbid. Our text history is short. I deleted a majority of them to free up space on my phone and I curse myself for it. But I still have his emails. I created a Google document and start copying and pasting my favorite lines.

The words were there, archived. But he was not an active part of the conversation anymore. I had so many questions for him.

— How do I have a career without you?

— What else did you want to do?

— Was my moderate success because of you?

— How do I live sober?

— How can we remain a family without you?

— Why were you so hard on me?

— Why were you so hard on yourself?

— Did part of you know that you were going to die?

— What do you wish you had told me before you died?

The information exists within his digital sphere — data for me to mine. Possible answers to my many, many questions.

From the book All That You Leave Behind by Erin Lee Carr, published by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2019 by Erin Lee Carr.

Published in the Winter 2019 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.