Amazing Grace

Every Tuesday evening, in a space that usually houses a Sunday school, UW medical students care for those who have nowhere else to turn.

Privacy is minimal at the clinic housed in Grace Episcopal Church in downtown Madison, but the UW medical students do what they can with the available space. In an exam “room” at the end of an L-shaped hall, student Tim Kufahl MDx’11 cares for a patient beneath church banners.

The men trickle in slowly. Some lean heavily on the metal railing as they ascend the cement stairs to take a seat on one of the metal folding chairs lining the dimly lit hallway. Most sit quietly, glancing up slightly as someone walks by, patiently waiting for a door to open.

On the other side of that door, students hurriedly gather papers, pens, clipboards, and other supplies as they receive last-minute instructions. For some, it’s familiar territory; for others, it’s the first time. All fairly brim with nervous anticipation. At around 8 p.m., the students are ready, and the door opens.

Every Tuesday night, while most of us are at home finishing dinner, UW medical students are taking blood pressure readings and gathering patient histories in the hallways of Grace Episcopal Church in downtown Madison. By 10 p.m., as many as sixteen patients have been seen and treated. Thanks to the dedication of these UW students and faculty volunteers, these patients, most of them homeless men who would otherwise go untreated, get the health care they need.

The Grace location is one of several medical clinics operated by the Medical Information Center (MEDiC), a program that has two unwavering goals: to improve the health of an underserved population and to give medical and other health care students what is literally a hands-on learning opportunity.

Although several practicing physicians rotate as volunteer supervisors, the clinics are staffed and managed by students who volunteer during their first and second years of training. The students are clearly embracing the medical school’s culture — an astounding 80 percent of UW med students volunteer at least once during those years.

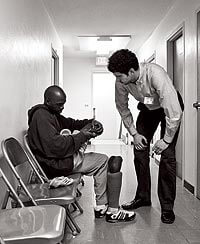

One of two coordinators at MEDiC’s Grace clinic during spring 2009, Michael DeVita ’06, MDx’11 leans down to talk with a patient who lost his lower leg to frostbite. DeVita keeps things running smoothly at the clinic, directing the other medical students and stepping in as needed to care for patients.

“I just fell in love with the clinics,” says Dhaval Desai ’08, MDx’12, who volunteered during his first year and, now in his second year, is serving as one of the student coordinators at the Grace clinic. “Doing something medically relevant while helping people in my community is why I came to medical school in the first place.”

For Megan Schultz ’03, MDx’11, it’s all about this medical school. “This is the most real thing we do as beginning medical students,” says Schultz, former president of the MEDiC Council, a thirty-member group that handles everything from scheduling to publicity. “I came here for school because of this program, and it is by far the best thing I’ve done here.”

MEDiC began in 1990 when seven medical students approached Ted Goodfriend, who today is an emeritus professor of medicine and pharmacology. With little clinical experience — but a desire to somehow contribute to social and medical needs — the students hoped that their professor could help steer them in the right direction. Someone suggested that Goodfriend check out the shelter at Grace Episcopal, where law students had already set up a clinic to provide legal counsel to the homeless.

Creating a medical clinic at the shelter seemed like a win-win proposition. The population there — homeless, but ambulatory, adult men — offered a medical experience that a beginning student could successfully undertake. In turn, while surgeries or other major procedures couldn’t be performed at the clinic, the students could help with conditions such as broken bones, acute infections, minor injuries, skin problems, and digestive disorders.

Goodfriend and several students began going to the shelter once a week in 1991. Soon after, a clinic opened at the Salvation Army to serve homeless families at the suggestion of Goodfriend’s wife, Mary Lou MS’88, a teacher who had many homeless children in her classroom. Today MEDiC operates six clinics, each serving a distinct population with its own needs and challenges. One, known as Safe Haven, provides ongoing care for homeless adults suffering from mental illness, a particular challenge for the homeless community.

Students volunteering at the clinic must complete a raft of paperwork before they can head home. Patient records are kept on site in case a patient makes a return visit. Under a new program, the students also record information about homeless veterans who seek medical care.

While the idea of medical students working in free clinics is not unique, the degree of control exerted by the MEDiC students is. The UW School of Medicine and Public Health supports the program, including providing a faculty adviser, Sharon Younkin, but the clinics are wholly coordinated by students.

When setting up the program, Goodfriend wanted to ensure that students who volunteered did so for the right reasons. Students receive neither pay nor academic credit for their work at the clinics. Instead, he says, they “actively participate in patient care while becoming aware of the social, economic, and access issues that affect these populations.”

They also learn that paying attention to patients, reassuring them, and engaging them in conversation often has as much therapeutic benefit as any pill.

Three of the six clinic sites, including the homeless shelter at Grace Episcopal, are run by Porchlight, Incorporated, a Madison-based nonprofit that provides shelter, housing, and support services to the homeless in Dane County. Within Madison alone, an estimated 3,500 people are without a place to live at some point each year. During 2008, Porchlight provided housing, counseling, job training, medical and legal assistance, and eviction-prevention services to around 12,700 people.

“Homelessness is on the rise — as is the number of people unable to get basic medical care,” says Steve Schooler, Porchlight’s executive director. “[MEDiC] clinics help fill a gap in our community’s social support services.”

Drugs and other medical supplies are limited at the Grace clinic. The medical students work with the clinic’s attending physician each week, doing the best they can for their patients, including some who return for treatment of chronic illnesses.

Goodfriend counts MEDiC as his proudest career accomplishment. “These clinics are the most gratifying thing I’ve done as a doctor,” he says. “But really, I didn’t do anything — it was the students coming to me wanting to do this, and it continues to be the students who are the stars, making this kind of care possible for some of our neediest people.”

When the Grace clinic opens each Tuesday evening, the MEDiC volunteers divide up patients and take them to exam rooms that are anything but typical. Students meet with patients at the end of a long L-shaped hall, in one of two rooms that most often serve as Sunday school classrooms, all the while doing their best to maintain patient privacy.

After initial chats with incoming patients, students present cases to the volunteer physician who is supervising that evening’s clinic. As they describe their patients, the doctors-to-be often realize they failed to ask questions that are important for developing diagnoses and treatment plans. But that’s all part of the learning process. When needed, the physician and student return to talk with a patient a second time, allowing the student to watch and learn as the physician talks with and examines the patient.

“The students inhabit the role they need to be in, even if they aren’t trained in that area yet. They ask questions and get the job done — it’s really quite amazing,” says Mark Linzer, a UW professor of internal medicine and one of the clinic’s supervising physicians.

By necessity, given the transient nature of the homeless population, the MEDiC sites operate more like battlefield clinics than traditional medical settings. Patients are treated quickly and sent on their way, making it especially difficult to treat chronic conditions such as diabetes.

After a student completes an initial examination at MEDiC’s Grace clinic, the attending physician or resident arrives to talk with the patient and complete the exam. Resident Ryan Kipp ’03, MD’07 exams a dog bite on a patient’s arm before discussing a treatment plan with medical student Tim Kufahl. Among the most common conditions seen at the clinic are animal bites, broken bones, skin infections, and colds.

But the students do what they can on a shoestring budget of less than $20,000 — most of which is donated. At Grace, two metal cabinets are filled with samples and generic versions of many common medications, as well as bandages, antacids, and toothbrushes. A pharmacist in La Crosse often helps MEDiC purchase drugs.

Despite the odds, the six clinics serve some 1,300 underinsured and underserved patients annually, and reach beyond medical care in helping the community. For example, students volunteering at the Southside and Salvation Army clinics also participate in Reach Out and Read, a national program that encourages childhood literacy, by advising parents on the importance of reading aloud to young children. They also distribute free books to kids in the clinic waiting areas.

Talk to nearly any MEDiC volunteer, and you’ll hear a refrain similar to that from Brian Cone ’07, MDx’11, now a third-year student: “It’s nice to be doing something other than butt-in-the-chair learning.” He and his fellow students are well aware that during the first two years of medical school, most of their time is spent in the classroom. The chance to work with actual patients usually doesn’t come until their third and fourth years.

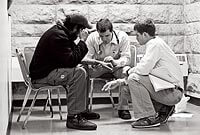

Tuesday nights pass in a blur of activity for medical students Dhaval Desai and Michael DeVita, left and center, and Shelly Schmoller ’05, x’11, right, who is studying to be a physician assistant. Before semester’s end, DeVita, one of two clinic coordinators, will help with the transition to new students and coordinators, one of whom will be Desai.

Second-year student Alex Froyshteter MDx’12 is grateful for that clinical exposure during the earlier stages of his medical training. “This is a very comfortable atmosphere for learning directly from the doctors,” he says about the Grace clinic. “It’s putting a face on something I only read about in a book — and having someone take the time to explain it to me.”

In turn, the patients are grateful for the students and their clinics. “The guys are really lucky to have this here,” says Richard, a homeless man receiving treatment at Grace for a dog bite. “I’ve been in shelters all over the country, and none of them have had this.”

As Richard trudges back down the stairs, a MEDiC student files his paperwork, then leads another man in need of care down the hall.

A Madison-based freelance writer, Erika Janik MA’04, MA’06 is glad to know that this generation of doctors-in-training is so community minded.

Published in the Winter 2009 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.