A Better Way to Teach 9/11

UW professor Jeremy Stoddard MS’01, PhD’96 discovers shortcomings in schools’ approach to the war on terror.

Stoddard says that, without an in-depth curriculum, students can easily fall prey to misinformation and conspiracies about 9/11.

People over a certain age can never forget the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. But what about people under that age? Twenty years after hijacked planes crashed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, young people need to know how these cataclysms transformed the world they were born into. How should middle schools and high schools help a new generation understand the 9/11 attacks and the controversial war on terror that followed?

That’s the subject of a 19-year study led by education professor Jeremy Stoddard MS’01, PhD’06. Stoddard, School of Education dean Diana Hess, and other collaborators have found significant shortcomings in the way students learn about 9/11 and the war on terror. Without an in-depth curriculum, they can easily fall prey to misinformation and conspiracies about the longest-running conflict in U.S. history. Fortunately, Stoddard’s team has a plan for turning things around.

What are some of the problems with the way schools cover 9/11?

A lot of people teach 9/11 on the anniversary because it doesn’t fit well into the U.S. history standards. They often memorialize it without giving either the historical context or the implications for today, because they don’t feel like they have the time. So students tend to have a limited understanding of the event, and a lot of what they do know is information from their families or what they have found online, including conspiracy theories.

What would be a better way to teach the subject?

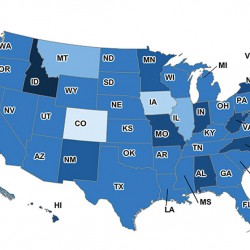

Ideally, you would help students understand the events leading up to 9/11, and then look at why the U.S. responded the way it did — for example, with legislation like the PATRIOT Act. I think it’s important for students to understand that we still have military and intelligence folks stationed in the Middle East and around the world as a direct result of how the global war on terror has been framed. If young people graduate high school and don’t know where the U.S. is involved around the world, we’re not doing a very good job of preparing them as citizens. And unfortunately, in most states, that’s a problem with how the social studies curriculum is designed.

How is your team working to improve the pedagogical approach to 9/11?

Teachers tell us they want materials that will help them inform students who have no idea what this event is, so we’re putting together primary resources and workshops around the 20th anniversary.

What are the most valuable resources to provide?

We’re focusing on things that aren’t usually included in the curriculum, like the experiences of veterans, challenging stereotypes of Muslims as terrorists, and the long-term health effects of 9/11 for people who worked at the World Trade Center site. We’ve also written articles to provide examples of what teachers are doing in their classrooms to challenge conspiracy theories about 9/11. So instead of teachers having to create their own lessons about this subject through trial and error, we’re trying to do some of that work for them.

Published in the Fall 2021 issue

Comments

jackyyy B September 10, 2025

I think we should talk more about the terrorist. Theirs a lot more talking about the effects and long term affects but not enough of the terrorist that caused it all.

Zachary Weavers September 10, 2025

I would like to do more study on this topic and compare and determine which idea of what actually happened on the scene of 911.