Building on Ancient Art Forms

Dyani White Hawk MFA’11’s work helps viewers to see Indigenous contributions with new eyes.

White Hawk’s intensive labor celebrates the under-recognized work of the many Indigenous women who made similar art throughout history. MacArthur Foundation

When artist Dyani White Hawk MFA’11 talks about the role of Indigenous peoples in art history, she doesn’t mince words.

“The way art history is taught today reflects how the contributions of Indigenous people to this continent are not recognized, honored, and celebrated as equal to their European and European American counterparts,” she says.

As one of the country’s most celebrated Indigenous artists, White Hawk is intent on changing that paradigm. She uses beadwork, quillwork, paintings, video, and installations threaded with ideas of community and ancestral relationships to land related to her Lakota heritage.

In 2023, she won a MacArthur Fellowship. The $800,000 stipend allows her the flexibility to focus on projects without financial pressure, but she’s also thankful for the network of “phenomenal thinkers” that the so-called genius grant allows her to interact with.

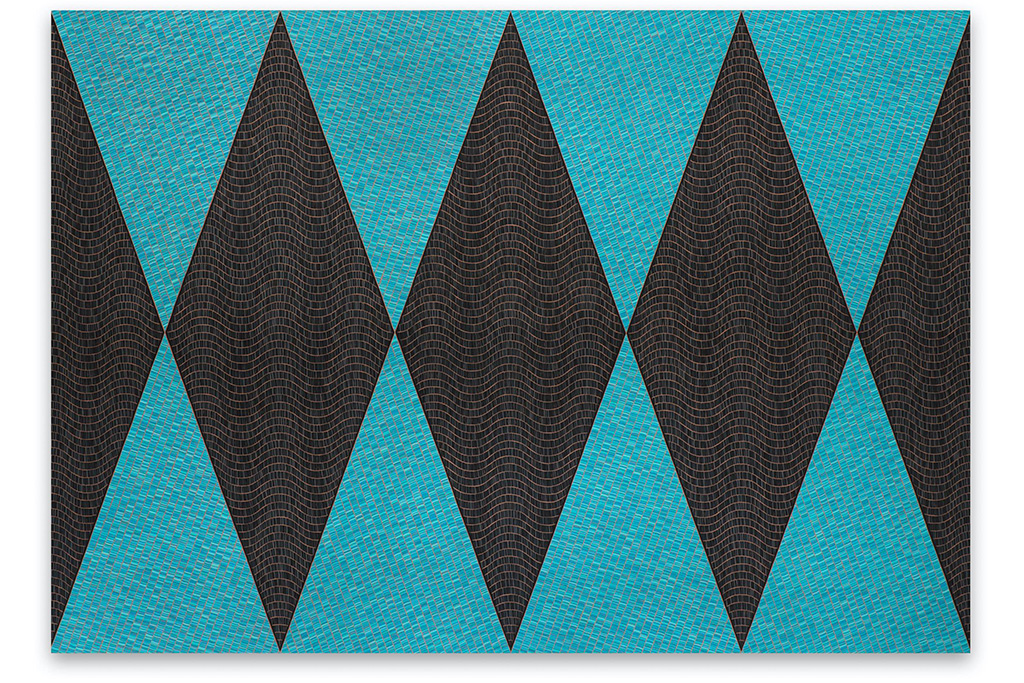

The Minneapolis artist boasts an impressive array of work, but her abstract paintings and beadwork are especially eye-catching. White Hawk often combines painting with bands of exacting, intricate beadwork shaped into geometric forms and patterns. Such intensive labor celebrates the under-recognized work of the many Indigenous women who made similar art throughout history.

She Gives (Quiet Strength VII)

84 x 120 in. Acrylic on canvas 2020. Rik Sferra

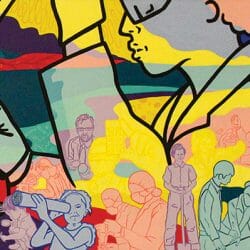

Untitled (All the Colors)

48 x 48 in. Acrylic glass bugle beads, synthetic sinew on canvas 2020. Rik Sferra

Most strikingly, she exhibited a 14-by-8-foot fully beaded painting at the prestigious Whitney Biennial exhibition in 2022, and the artwork makes a statement with its scale. “There’s a quiet strength to the piece,” she says, explaining that she wanted to intentionally take up space equivalent to that typically occupied by non-Indigenous male artists.

In a video created for the exhibition, she points out that abstract art was not invented by European artists, as many believe, but that Indigenous peoples have been creating abstract art for millennia.

Next for White Hawk is exhibiting more of her work in galleries across the United States, as well as gearing up for a major exhibition at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in 2025.

She says she couldn’t be more thankful she earned her master of fine arts on a campus where she felt supported. “Here [at UW–Madison] was a program that had a strong number of Indigenous faculty, which was really important to me. They understood my history, my lineage, and my perspective on education.”

Published in the Winter 2024 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.