Land of the Ho-Chunk

A canoe recovered from Lake Mendota tells a story that long predates UW–Madison.

The plot of Disney’s Frozen II is driven by a thematic refrain: “water has memory.” In the movie, dams and streams and ice reveal both heart-wrenching details of the characters’ heritage and ugly truths long submerged in a murky history. Last summer, when archaeologists with the Wisconsin Historical Society discovered a canoe at the bottom of Lake Mendota, the heart of this Disney tale beat a little closer to home.

Initially, the archaeologists thought it was a relatively young canoe — an artifact of the 1800s or a Boy Scouts project from the 1950s. The revelation of its true age took their breath away: the vessel was 1,200 years old, built around 800 CE by early ancestors of the Ho-Chunk Nation.

News of the canoe’s discovery and recovery made waves that traveled the world, but the impact is felt most strongly at its source. For some, the vessel is a tangible reminder of a history frequently forgotten in the wake of watersports and watercolor Terrace sunsets. For others, it affirms a truth as old as the ancient lake herself, one that reflects on her glassy surface and rests in her cloudy depths.

“Madison is the water,” says Molli Pauliot x’94, MA’20, PhDx’23, a cultural anthropology student and member of the Ho-Chunk Nation’s Buffalo clan. It was the water that sustained this area’s earliest residents, and it’s the water that has drawn everyone since.

Water has memory — sometimes so vivid that it freezes a moment in the form of a dugout canoe. Lake Mendota is speaking. A great many people are eager to hear what she has to say.

“I think I found something”: The first glimpse of the canoe in Lake Mendota. Wisconsin Historical Society

A Whisper Underwater

June 11, 2021, was a perfect summer day in Madison: the weather was warm, and Mendota was beautiful. For Tamara Thomsen ’91, MS’93, a maritime archaeologist with the Wisconsin Historical Society, these were prime conditions to do no work at all. Equipped with diver propulsion vehicles — underwater scooters — Thomsen and Mallory Dragt ’20 set out to a popular dive spot off the lake’s southwest shore.

“I have been to [this dive site] probably a hundred times, and thousands of divers have been there, too,” says Thomsen. “We were going to scooter around and chase fish, and then pick up trash.”

Halfway into their joyride, Dragt signaled to Thomsen that it was time to circle back to the boat. But Thomsen was focused on a log sticking out of the lake’s wall. In the rare clarity of Mendota’s June waters, the log resembled the dugout canoes she had spent recent years studying around the state. She counted the minutes it took to scooter back to the boat in hopes of finding the canoe again later that day, this time not as a recreational diver, but as an archaeologist.

Amy Rosebrough MA’96, PhD’10 was working from home when she got a call from Thomsen, her colleague at the historical society.

“I think I found something,” Thomsen said.

Rosebrough is a terrestrial archaeologist in the State Historic Preservation Office and an expert on the Indigenous peoples who lived in Wisconsin and surrounding areas during the Late Woodland period, which lasted from 500 CE through 1200 CE. A self-described “landlubbing archaeologist,” she wasn’t about to suit up and dive in with Thomsen, but on a day like this, she couldn’t refuse an opportunity to sit on the boat and offer her expertise.

Back in the water, Thomsen located the canoe again, recorded its coordinates, and investigated its condition. She fanned around the edges of the wood, expecting to find a fragment, only to discover the vessel almost entirely intact. She resurfaced to share photos with Rosebrough before returning to retrieve the “weird, colorful rocks” she reported finding nearby.

“We put them in a row and looked them over, and I thought, well, this is very, very strange because they’re not round, they’re not tumbled, and they’re not smooth like you would see if they were dropped by a glacier,” Rosebrough says. “But I couldn’t, at that point, figure out what on earth they were.”

Thomsen returned the rocks, measured the canoe, and reburied their discovery. That evening, Rosebrough realized that the rocks were net sinkers, tools thought to be used by Late Woodland fishermen. Intrigue quickly became excitement. What memories would Mendota reveal?

Resurfacing

The Wisconsin Historical Society was between state archaeologists in June 2021, so further inquiry into the canoe’s origins was put on hold until the arrival of Jim Skibo. Skibo was a professor of archaeology at Illinois State University for 27 years before coming to the historical society.

When he learned of a story resting at the bottom of Lake Mendota, he committed to telling it. Thomsen retrieved a hair-sized sample of the wood from the canoe to send out for radiocarbon dating.

“When Jim announced what it was, I almost fell on the floor,” Rosebrough says. “From that time period, we have things made out of stone. If the preservation’s really good, we’ve got a bone tool or two. We’ve got pottery, but even that is usually broken into tiny little pieces, so we were making history based on scraps and impressions and the occasional mound.”

But Mendota, a meticulous conservator, kept this piece of history safe: packed tightly into the lake bed, the wooden canoe evaded sunlight, invasive species, and centuries of other vessels and visitors.

“This is a chance to touch a piece of history that should, by all accounts, have turned into dust a couple of decades after it was abandoned,” Rosebrough says.

On November 2, 2021, after months of careful planning and practicing, Thomsen, Skibo, maritime archaeologist Caitlin Zant, and a group made up of experienced volunteers and divers from the Dane County Sheriff’s Office executed a maneuver never before performed by the historical society when they excavated the canoe from the lake. The process took hours, during which a crowd amassed on the shore where Rosebrough was communicating with the team out on the water and fielding questions from curious onlookers and media outlets.

The canoe — the oldest intact vessel ever recovered from Wisconsin waters — emerged to applause, cheers, and tears before being carted away to the State Archive Preservation Facility. The recovery made headlines from CNN to the BBC. The canoe itself harbors many more stories to tell.

Ancestral Footprint

To appreciate the canoe’s stories, you have to know the people who made it. While Lake Mendota’s present-day shores may be the most populated they’ve ever been, the vast majority of her history has been spent in the company of the Ho-Chunk Nation, who have called these waters home since time immemorial.

“We’ve been in Madison as long as we’ve been Ho-Chunk, and the Ho-Chunk have been there since before it was Madison,” says Casey Brown x’04, public relations officer of the Ho-Chunk Nation and member of the Bear clan.

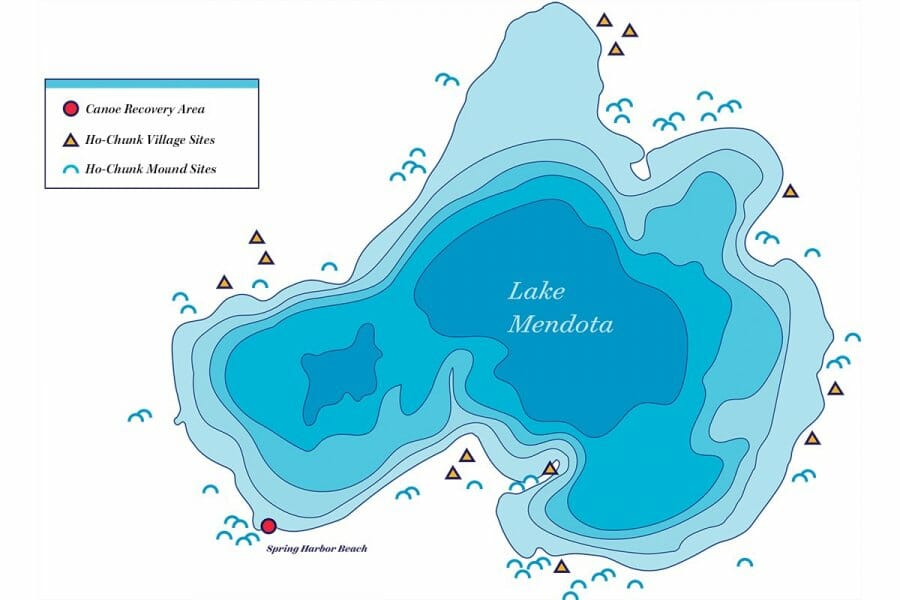

According to Brown, the tribe’s oral histories indicate that the Ho-Chunk first entered the world at the Red Banks (near present-day Green Bay). From there, they spread throughout the Midwest, from the Mississippi River to Lake Michigan. Archaeologists refer to them as the Late Woodland people or the Effigy Moundbuilders after the animal- and spirit-shaped burial mounds with which they sculpted the landscape. To the modern Ho-Chunk Nation, they’re simply centuries-removed kin who established the tribe’s ancestral footprint in the Madison area: Teejop, or “Four Lakes,” a region whose beauty lies in its waters, and whose waters spring from stories.

One Ho-Chunk account of the Four Lakes’ origins tells of Man’una, or “Earthmaker,” who was traveling through the region when he stopped to rest. He filled his kettle with spring water, caa (deer meat), and roots, and set it atop a fire to cook when he heard a sound in the woods. He left to investigate, thinking it might be his friend Bear. When he returned, the kettle was on its side and the water flowed into depressions in the earth, forming the Four Lakes.

Another Ho-Chunk story tells of a man who once fell so deeply in love with a water spirit that he turned into a fish to follow her, carving out the Four Lakes in a pursuit that culminated in the creation of the largest one, Wąąkšikhomįk, or “Where the Man Lies.” To this day, mounds that resemble water spirits can be located just off Mendota’s shores.

The presence of mounds in the area indicates a landscape that allowed for exploration and education, its residents’ basic needs having been readily met by their environment. These early Ho-Chunk were expert navigators, engineers, and astronomers, learning from the land and sky and innovating with the abundant resources.

The mounds themselves are teachers to this day, not only educating people about their builders, but also serving their original purpose by indicating directions and reflecting cosmic phenomena such as solstices.

“The entire Four Lakes area is essentially a university,” Brown says. “Even before the UW was there, the Ho-Chunk were using it as a teaching tool.”

And it continues to be. The Ho-Chunk Nation worked closely with the historical society throughout the canoe retrieval process, and they’ll continue to be involved in helping the canoe tell its story. After all, it’s their story, too.

Mendota’s Oldest Companions

As the leading expert on the ancestral Ho-Chunk who resided on Mendota’s shores during the Late Woodland period, Rosebrough knows more than most Western academics about their customs, technology, and ways of life. With the discovery of the canoe, she also has the most questions.

In the summer, the early, seminomadic Ho-Chunk lived in small villages along lakeshores and riverbanks and grew gardens of sunflowers, squash, goosefoot, and little barley. In the winter, they spread out to preserve resources and the environment. Hunting was integral to their sustenance; archaeologists have recovered arrow and spear points, skinning knives, and hide scrapers, along with remnants of bird and deer bone at many village sites. The importance of fishing was an educated guess.

“We’ve assumed that they were fishing and working on the lakes because the pottery is decorated with the impressions of fabric and cordage and, in some cases, nets,” Rosebrough says. Along with a small collection of harpoons and bits of fish bone at village sites, the canoe and its net sinkers are concrete evidence of fishing in these communities, which raises more questions. Were they fishing onshore or offshore? In deep water, where the big catches lurked? With nets alone, or are there hooks yet to be found?

Inquiries into fishing are just the start. According to Rosebrough, the historical society already has stone tools believed to be axes dating back nearly 10,000 years. By comparing the tools to the markings on the canoe, archaeologists can determine if these implements, once thought to be used for cutting down trees, were actually used for canoe-building.

Rosebrough is also interested in exploring the vessel’s capability for travel. Archaeological evidence suggests that early Ho-Chunk traded with the Cahokians, Indigenous peoples who lived just across the Mississippi River from present-day Saint Louis. The Cahokians were almost certainly traveling up the river to reach the northern tribes — could this canoe have traversed rough waters like the Mississippi or the Great Lakes to reach distant civilizations before meeting its end in Lake Mendota?

Wisconsin’s First Shipwreck

Wisconsin is distinguished by its more than 800 miles of Great Lakes shoreline. The state flag, first adopted in 1863, features a sailor and an anchor, nods to Wisconsin’s early shipyards and nautical industries, the remnants of which lie at the bottom of lakes and rivers and occasionally wash ashore or startle anglers before revealing details of historic shipbuilding in the Midwest. But Wisconsin’s maritime history far predates its flag.

Thomsen is an expert in Wisconsin shipwrecks and spends a great deal of her time documenting and protecting these historic elements. With the canoe, she may have found the very first.

“When Euro-Americans are here and ships go down, we call them a shipwreck. When canoes go down and are found, we call them an artifact,” Skibo says. “But this was a shipwreck.”

Most Indigenous dugout canoes found in Wisconsin were recovered from shallow waters because it was common for early fishermen to cache their canoes offshore in the fall — to commit them to the water’s memory — and recover them in the spring. This canoe was found in 27 feet of water, far from the shores on which it would have been stowed.

The state of the canoe also points toward maritime mishap. Of the minimal damage the canoe has sustained, its oldest flaw may have also been its demise: a heel-sized hole in one end. Wood contains knots that stubbornly refuse to warp with the wood around them, causing them to become weak and fall out. While many recovered canoes show signs of patchwork and repairs, this one’s hole remains.

“Archeologists love touching individual moments: the fingerprint impressed into the pot, the footprint in the floor of a dirt-floored house,” Rosebrough says. “We have a moment here where somebody was either in that canoe or had stashed their net and gear in that canoe, and it went down.”

Like the side-wheel steamers Thomsen traces back to 19th- and 20th-century shipyards, the canoe offers insight into the building techniques of its makers. The USDA Forest Products Laboratory on the UW campus determined that the canoe is made of white oak, a hard and watertight wood native to southern Wisconsin and known to the Ho-Chunk, to whom it is sacred, as caašgegura. Dark soot inside the hull and markings from stone tools suggest the use of burning and scraping to create the vessel. According to Thomsen, wear on the bottom of the canoe can indicate which ends might have been the bow and the stern. Studying its construction can also help archaeologists track the progression of canoe-building through time and across tribes.

“This canoe would be great, like a pickup truck,” Skibo says. It may not have been built for speed or agility, but it could carry a couple of fishermen out to their nets and tote the cargo home — until it didn’t.

To test this theory, Skibo partnered with Lennon Rodgers, director of the UW Grainger Engineering Design Innovation Lab, to investigate the canoe’s structural integrity. Rodgers’s 3-D scans of the canoe have yielded detailed digital and physical models that will be used to test its flotation and satisfy Rosebrough’s curiosity about its maritime capabilities. They can also help determine whether a dislodged knot could truly be the culprit in its ruin.

The likelihood of shipwreck also raised the question of whether the canoe might indicate a burial, which would have stopped the excavation in its tracks. Wisconsin State Statute 157.70 prevents the disturbance of human remains of any kind and assigns immediate ownership of discovered burials or funerary objects to the respective tribes. Review of culturally specific burial practices and careful dredging of the area around the canoe ruled out this possibility. Still, the canoe’s location and condition create emotional ties that transcend centuries and generate wonder about the person whose vessel went under one day.

“Were they panicking? Were they upset? Were they looking at shore going, ‘Dang it, I didn’t want to get wet today’?” Rosebrough asks. “To reach back and start to think about one individual on one day — one moment of one day — we can empathize with them as another human being.”

People of the Mother Tongue

For some, these ties through time run deeper than the shared experience of a watercraft lost to the lake.

While the Ho-Chunk are the region’s longest-standing residents, their numbers have fluctuated over thousands of years after repeated attempts to eradicate them. According to Rosebrough, disease and intertribal wars instigated by the arrival of French fur traders in the 17th century decimated the Ho-Chunk population. The tribe’s oral histories indicate that, at one point, there were only 50 adult Ho-Chunk men. Later, federal policy displaced the Ho-Chunk from their ancestral lands and allowed for the destruction of mounds and other earthworks.

“When you’re colonizing people, you take over their most beautiful sites, their most sacred sites, and you put your site on top of it,” Pauliot says. “That’s why the capital’s in Madison.”

Perhaps the most recent and haunting attempt at eliminating Indigenous influence was the rise of residential schools. The Ho-Chunk language provided the foundation for many Siouan languages throughout the American Midwest and West; the tribe is known as the “People of the Loud Voice,” “People of the Sacred Voice,” or “People of the Mother Tongue.” After generations of cultural undoing in residential schools, the speakers of the “mother tongue” — those who taught language and its culturally preservative capabilities to others — are few.

Oral histories, the intangible and invaluable records of time from which the Ho-Chunk derive their sense of identity and connection with the past, do not die with the language, but they will suffer immensely from its absence.

“That’s why historic preservation is so important,” Brown says. “It is almost a form of protest, [us] just being alive.”

What is a canoe, then, to those who need no evidence of their own existence and who rely not on things, but on stories?

“It’s just another part of our culture,” says Bill Quackenbush, tribal historic preservation officer with the Ho-Chunk Nation and member of the Deer clan. “We don’t need to see items brought out of the water just to reassert that we are here.”

For the Ho-Chunk, history and culture are not lying at the bottom of Lake Mendota; they’re taking place on and around it. They keep their ways alive through the continuation of skills, values, and practices that have existed even longer than the canoe. This, Brown says, is how a nation survives.

One way they have done this is by building a canoe themselves. Prior to the discovery in Lake Mendota, Quackenbush gathered a group of Ho-Chunk youth to make their own dugout canoe out of a cottonwood tree. The team spent months burning, scraping, and sawing the log and, this past June, embarked on a weeklong journey through the Four Lakes region in their completed vessel, which included a stop along the Yahara River to visit the new canoe’s oldest known ancestor. Even as language is lost, water remembers.

“We’re going to show these kids what it means to be Ho-Chunk,” Brown says. “This is Ho-Chunk land. This is where you’re supposed to be. They have a 1,000-year-old canoe, but your people have been here, and they’re still going to be here.”

Reflecting on previous canoe-building experiences, Brown recalls that a vessel is imbued with the spirits of its creators. Submerged in busy waters, the ancient vessel found in Lake Mendota had every reason to disappear in the 1,000-plus years since it sank. It should have disintegrated into the lake bed, splintered apart, broken into bits under the churning of boat motors, or been eaten by zebra mussels — and yet. The People of the Mother Tongue had the first word, and they will certainly have the last.

Dehydrating History

Lake Mendota is not done speaking. Since the retrieval of the dugout canoe, two more have been located near the site of the first. These vessels were found in fragments and will remain in their final resting place, though radiocarbon-dating will reveal their respective ages.

The discovery of the additional canoes in such proximity challenges the theory of shipwreck: in addition to dating the new canoes, Skibo is currently working to determine the location of ancient shorelines — some of the research that has yet to be conducted on this most-studied lake. Perhaps these canoes weren’t sunk, but were simply forgotten.

Today, the original canoe is back in water, this time in a rubber-lined vat in the State Archive Preservation Facility on Madison’s east side, just down shore from its resting place of over a millennium. It’s one year into a three-year preservation process involving a purified-water bath, UV-lights, and, eventually, polyethylene glycol, or PEG.

When removed from the environment that kept it safe through thousands of years, the canoe was held together only by the water in its cells. By gradually adding PEG to the solution in which the canoe rests, the preservative will replace the water in its cells before it’s freeze-dried to remove any excess water the PEG didn’t reach.

It’s up to us to preserve its memory now. •

Megan Provost ’20 is a staff writer for On Wisconsin.

Published in the Fall 2022 issue

Comments

Iver Anderson September 22, 2022

Megan,

You did an excellent job on this article! Packed with historical facts and carried on a theme of the water having memory (from Frozen)—–very readable and informative. I still want more information on the cottonwood dugout canoe (dimensions, pictures, journey, builders, etc.). Also, do we need to wait 3 years to see the canoe, when it is done being dried out in the SAPF? I am glad that no more detail was provided on the location in Mendota that it was found! Is there a guide to all of the Lake Mendota mounds? There should be a trail or at least markers to describe them. Thanks for lighting my curiosity on this!

Best regards.,

Iver

James Santilli '75 School of Pharmacy September 28, 2022

HI

I truly enjoyed the article until it referred to the choosing of Madison as the Capital of Wisconsin due to colonization (Pauliot). Initially I found this paragraph off- putting. I did much research and found that most of the Ho-Chunk were removed from the Madison area by 1833. This then allowed for land speculation with Madison being chosen for the Capital. I do not believe Pauliot “When you’re colonizing people, you take over their most beautiful sites, their most sacred sites and you put your site on top of it. That’s why the capital’s in Madison”. I felt this activist statement unnecessary. It did get my attention, though negatively. What does this statement have to do with the canoe?