Jessica Weeks

Jessica Weeks is fascinated by the “dark side” of international relations: dictatorships. But her award-winning research combats the black-and-white view of authoritarian regimes and democracies. Dictators at War and Peace, published in 2014, classifies regimes to better understand them: bosses/strongmen, with an unchecked personalist leader; juntas, with influential military elites; and machines, with influential political elites. Weeks, a UW associate professor of political science, spoke to members of the U.S. intelligence community in Washington, DC, last year as they grappled with how to contain North Korea.

How do authoritarian regimes differ?

Who is inside the regime really matters. Boss and strongman regimes have the stereotypical dictator, like Saddam Hussein, Mao, Stalin, Hitler. One person has a lot of power and, because of that, can make decisions without too much concern that people within the regime will disagree or try to get rid of him. But when you don’t have people helping you make a decision or [holding you accountable], that often leads to suboptimal outcomes. These leaders tend to fight really risky wars, start more wars, and lose a lot more frequently. … Machines, I argue, are the most peaceful kinds of regimes. These include the Soviet Union after Stalin and China after Mao. They don’t fight as many wars and tend to have much better outcomes when they fight. Juntas are more likely to [engage in war] because the military officers are more likely to see force as a viable option and policy tool. They end up falling in between the machines and the bosses.

According to your book, machine regimes are just as risk averse as democracies when it comes to initiating force — and are just as successful when they do go to war. Why?

It’s because of the risks that the leader would face if they undertook foolish foreign-policy decisions. A leader in a democracy needs to think about what the electoral consequences would be if they lost a war. You don’t pick wars that you can’t win. You have the same dynamic going on in these machines. The leader knows — they’re not thinking about the public, per se — but they know that if they start a war and it goes badly, then they could be ousted by the other top people in the regime. The accountability is coming from other people within the regime rather than the public at large.

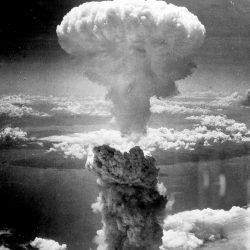

How do nuclear capabilities fit into this discussion?

I have [research] that finds that boss and strongman regimes are more likely to pursue nuclear weapons than machines and juntas. It’s similar dynamics. These leaders face fewer constraints. When a country tries to pursue nuclear weapons, it often faces a lot of costs from the international community. But the leaders don’t really internalize those in the same way. So you end up seeing that the same regimes that fight a lot of wars are often also trying to acquire these weapons.

What did you think of the summit with North Korea?

I think the U.S. [needs] to be extremely cautious about any promises [from] North Korea. … If Kim [Jong-un] made a promise and then went back on it, there are going to be no domestic consequences for that — because there’s no one to criticize him. It’s the quintessential boss regime.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Preston Schmitt ’14

Published in the Fall 2018 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.