The Warlord’s Biographer

During a presidential run in 2004, Abdul Rashid Dostum, the subject of a book by Brian WIlliams PhD’99, climbed on top of a horse and waved at throngs of supporters at a campaign rally in a Kabul stadium in Afghanistan. AP PHOTO/David Guttenfelder

Brian Glyn Williams travels to the world’s most dangerous regions to learn more about our surprising allies in the War on Terror.

Like many Americans, Brian Glyn Williams PhD’99 spent last summer and fall closely tracking a contentious, historic election that would shape a nation’s future. But unlike most Americans, the race he watched wasn’t one of the U.S. midterms.

Williams’s attention was focused on Afghanistan’s presidential election, where, after two votes and several months of audits, Ashraf Ghani secured the country’s first democratic transfer of power. But it wasn’t Ghani whom Williams cared most about — it was Ghani’s vice president, Abdul Rashid Dostum. When the final results were announced, Williams sent Dostum his personal congratulations.

Dostum isn’t just any rising politician in just any developing country. Born in a rural village, he climbed first to regional and then to national prominence in the place where the United States has fought its longest war. His story is a rags-to-guns-to-riches tale complete with ethnic battles, geopolitical intrigue, covert operations, and even a mythical death ray.

It’s also the story of Williams’s career.

Apocalyptic ghost zone

Williams’s first day in front of a classroom at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth went about as he expected. The brand-new professor of Islamic history surveyed the handful of students who had signed up for his course on central Asian history from the time of Genghis Khan to the present.

“Have you ever heard of a Muslim theocracy called the Taliban?” he asked. Only one student raised a hand. The date was September 5, 2001.

When the World Trade Center towers fell less than a week later, Williams was invited to visit Ground Zero by a friend who worked nearby. “He called me up and said, ‘[Al-Qaeda has] made the news. Come see their handiwork,’ ” Williams says. He rushed to Manhattan, put on a mask, and stepped into what he recalls as an “apocalyptic ghost zone.”

Williams watched with horror as human remains were removed from the wreckage of the skyscrapers. He was shaken by the idea that Americans had become victims of a terror group closely allied with the Taliban, and he knew at that moment that his life was about to change. As the country tried to make sense of what had just happened, he was tapped as an expert source for national media interviews, and he gave several public talks to packed halls at UMass.

“I was someone who could infuse knowledge at a time of urgency,” he says.

The class roster for his course on central Asian history swelled well past one hundred.

Williams had, essentially, spent a lifetime studying the places and cultures he was now asked to explain. During a childhood spent living in Wales and Florida, he developed an interest in stories about the horse-mounted Afghan warriors who faced off against the invading Soviets during the Cold War. At the time, Williams romanticized the Afghan mujahideen forces. “The rebels in the ‘land that time forgot’ were standing up to these Communists to protect their faith, their land, and [their] families,” he says.

That interest motivated Williams to study Russian as an undergraduate at Stetson University in Florida and then to pursue master’s degrees in Russian history and Central Asian studies at Indiana University, where the CIA regularly recruited for operatives before the Gulf War. Williams opted for academia and pursuit of a doctorate instead and headed to Wisconsin, home to one of the few university programs in the country dedicated to Central Asian studies.

It was also the only place where Williams knew he could focus on Afghanistan. His adviser, Kemal Karpat, a renowned Turkish specialist and emeritus professor now based in Istanbul, encouraged his interests. “I had a tremendous education there,” says Williams of his time at the UW. “The chance to study an obscure part of the world was a career builder for me. It made me who I am.”

Williams realized early in his doctoral program that he wasn’t cut out for a career in “a dusty archive.” Instead, he was drawn to the idea of studying history as it unfolded to explain — and perhaps to help shape — current events. In 1997, he moved to a region of Uzbekistan just north of the Afghanistan border for his dissertation fieldwork. While there, he witnessed the rise of an unknown group of zealots called The Students, or, in Pashto, the Taliban, which was rapidly attracting new members and allies, including a faction of the al-Qaeda army.

Williams headed to the border to get closer to the action and began hearing stories about an ethnically Uzbek (Turkic-Mongol) warlord named Dostum, who had snuck back into Afghanistan after years in exile to help lead a new, tenuous coalition against the Taliban. Though Williams eventually turned his attention back to his dissertation, he developed a deep fascination with Dostum. “It was my dream to meet him,” Williams says, but at the time, travel into Afghanistan was impossible.

Instead, Williams traveled north to the University of London, where he began teaching in 1999. While there, he was invited by Scotland Yard to become an adviser on the conflict in Chechnya and to provide early insights about the Taliban. Then came a whirlwind of projects, including fieldwork in Kosovo during the aftermath of that country’s ethnic war and a trip to Macedonia to meet with rebel insurgents — a move that promptly got Williams arrested by the Macedonian Army. Thanks to his dual British and American citizenship, he was released after only a few hours, but Williams says the experience was a turning point.

“That night, as we sat in the pub, it sort of empowered me,” he says. “You can do field research in potentially dangerous situations and get away with it.”

Why should I trust you?

In 2003, Williams managed to secure a grant to travel to Afghanistan to attempt an interview with Dostum. Flying from Boston to Kabul can take more than a day, sometimes two, but getting to the capital city was the easiest part of Williams’s odyssey. “Afghanistan is the only country where you can experience the Middle Ages,” he says. Sheep roamed the city’s streets.

Western reporters have described Dostum as an “an ogre” and “a monster who burns people alive.” These depictions made him wary of talking with foreigners and especially of talking to Americans, who he believed had turned their backs on him in the aftermath of Bai Beche — the U.S. battle that led to the overthrow of the Taliban and was won, in large part, by horse-mounted Uzbek cavalry wearing turbans and robes.

In October 2001, teams from the CIA and U.S. Special Forces coordinated with Dostum’s guerrilla army to launch an attack against the Taliban, who refused to hand over their Al-Qaeda guest, Osama bin Laden. Though U.S. military officers anticipated the guerrillas would need until spring to prepare an attack, Dostum was ready to move almost immediately. On November 5, some two thousand Uzbek horsemen charged into nine thousand Taliban fighters and heavy tank fire. As they did so, the Green Berets called in coordinates for U.S. planes to drop laser-guided bombs from above.

During the Bai Beche attack, Dostum spread a rumor that he was in possession of a death ray. Each time a plane dropped a bomb, Dostum was informed by radio. He would point at the target just before it exploded and broadcast to the Taliban that he was allied with Azrail, the Angel of Death. The Taliban soldiers surrendered in droves. “That scene inspired me to write a book,” Williams says. “The cavalry attack broke the spine of the Taliban army in the north.”

Williams has tracked down multiple military reports that acknowledge Dostum’s role in the success of the Bai Beche offensive. However, after Dostum’s troops left hundreds, and possibly thousands, of Taliban prisoners to die in metal truck containers that December, U.S. government officials distanced themselves publicly from the warlord. Dostum felt he had been used.

Despite Dostum’s aversion to American visitors, Williams was determined to meet him, and the two had mutual friends. Turkey had granted asylum to Dostum after the Taliban briefly conquered Dostum’s northern territory in 1997, so when the Turkish embassy sent word that it could vouch for Williams, the warlord agreed to receive him. In 2003, a convoy of more than one hundred bodyguards — all wielding AK-47s — was arranged to transport Williams from Kabul to Dostum’s compound in the northern desert.

They drove north through the Hindu Kush Mountains to a location near Mazar-e-Sharif, a shrine well known for its beautiful, blue-domed mosque, which local residents believe contains special powers of protection. A crowd of elders was waiting to greet Williams when he arrived in the middle of the night, and he was directed to Dostum, who sat watching Williams from a throne-like armchair.

Williams stood through “some of the longest seconds of my life,” he says, before Dostum spoke: “I’m sure you have many questions for me, because you’ve come all the way from America. But I have a question for you, my friend. Why should I trust you?”

Williams replied in Turkish: “Well, Pasha [general],” he said, “I’m here to tell your story. Let me live with you as the first outsider to write the Dostum epic.”

Flattery and the promise to set his reputational record straight appealed to Dostum. He invited Williams to sit down, eat a Turkish biscuit, turn on his camcorder, and start asking questions. For the next couple of months, Williams lived at the compound and spent hours with Dostum, his family, his men, and even his prisoners.

Williams and his wife, Feyza, meet with Dostum at his compound in Sheberghan during Williams’s second visit to northern Afghanistan in 2005. On his first visit two years earlier, Williams had been accompanied by a convoy of more than 100 bodyguards — all wielding AK-47s — who transported him from Kabul to the general’s compound in the northern desert. Courtesy of Brian Williams.

At the time of Williams’s visit, Dostum was holding an estimated five thousand captured Taliban soldiers in a medieval fortress. Williams was guided through giant metal doors into the prison’s central corridor, where thousands of men looked down from their cells at the blond, blue-eyed American. He interviewed several prisoners, who held a range of opinions about Americans and about their own involvement in jihad. Some were fanatics; some were farmers who had joined the Taliban for the promise of $700. “One guy lost his two brothers, and he wanted me to call his baba [father] and tell him,” Williams says. “Another guy was a mullah, and he told me he’d kill me if he wasn’t in this prison. He spat at me.”

Williams realized that most of the prisoners he spoke with had no idea their al-Qaeda allies had attacked the United States. “A lot of them were skeptical. There was this real sense that America was the bad guy, that we had invaded and didn’t belong there,” he says. “They thought we were like the Russians.”

Black, white, gray

At first glance, Dostum may seem an unlikely ally for the U.S. military. After all, the Afghan Communist Army spent the 1970s and ’80s battling against mujahideen fundamentalist groups supported by the CIA.

At the beginning of his career, Dostum viewed the Communists he fought for as advocates for equality and proponents of a secular society free from Islamic law. For years, he’s identified himself as a moderate secularist rather than as a Communist, but Williams says that nuance was lost on the CIA intelligence agents who lost track of him during the 1990s.

When the Soviet Union collapsed and Russia withdrew funding for its allies in Afghanistan, Dostum aligned himself with former mujahideen leaders from various ethnic groups and overthrew Mohammad Najibullah, the Communist president who had begun disarming his former friends — a move the mujahideen interpreted as a sign of impending subjugation. Dostum’s new alliance broke down quickly after the presidential coup, however, when he was snubbed for a position in the new government. A few years later, Dostum tried partnering with a particularly brutal warlord, an attempt that resulted in a failed coup and a series of sieges that killed more than twenty-five thousand people in Kabul during the mid-1990s.

At the same time, the Taliban’s ideology was spreading across Afghanistan. Eventually, warring ethnic leaders in the north realized they faced a common enemy: the Taliban. The extremist group had severely restricted the rights of women in its territories and imposed harsh religious requirements on men, too. When the Taliban publicly tortured and killed Najibullah, it became clear to Afghanistan’s most powerful figures that something had to be done.

From his base in Mazar-e-Sharif, Dostum ruled a northern territory that was one of the few remaining sanctuaries where women could attend a university and move freely in public without male escorts or burqas. But one of Dostum’s Uzbek countrymen betrayed him and accepted a $200,000 bribe to turn his personal army on Dostum’s forces. The Taliban then overran Mazar-e-Sharif, and Dostum fled into exile in 1997.

Right after 9/11, the CIA knew little about Dostum’s complex web of alliances and the motivations behind them. According to Williams’s research, the dossier on Dostum that the U.S. Army used during preparations for Bai Beche was riddled with errors. It described him as a frail man in his eighties who was missing an arm and harbored a hatred for Americans. None of this was true; in 2001, Dostum was forty-seven years old, in possession of both arms, and thought of the Americans as his saving grace.

Williams’s work provides the first significant alternative to popular Western depictions of Dostum as a tribal killer who couldn’t possibly have contributed meaningfully to the strategic plan behind Bai Beche. “Americans see the world in black and white. But the world is very gray. It’s complex,” Williams says, explaining that his main goal was to present a fuller picture of Dostum’s involvement in the War on Terror. “This book took me a decade. Journalists don’t have that kind of extended deadline. I can probe much, much deeper as a professional scholar and educate journalists, teach them what they missed in their rush for the headlines.”

After the 2003 visit, Williams returned to Dostum’s compound twice more. The second time, his wife, Feyza Williams, came along — over Williams’s objections. “I said, ‘It’s too dangerous,’ and she said, ‘Well, if it’s too dangerous, then why are you going?’ I backtracked and said, ‘No, it’s not so dangerous,’ and that was it,” he says.

She and Dostum were fast friends.

Over the next few years, the “Dostum epic” was interrupted by various projects. In 2007, the U.S. government asked Williams to conduct a study that tracked Taliban suicide bombings across southeastern Afghanistan. A year later, he served as an expert witness at the Guantanamo Bay trial of Osama bin Laden’s personal driver. Eventually, after tracking down CIA agents and a few of the Green Berets to corroborate Dostum’s account of Bai Beche, Williams kept his word and finished the book.

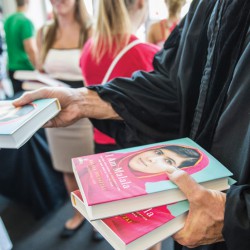

Initially, publishers rejected it out of a perception that Americans were tired of the War on Terror. But that perception changed when bin Laden was killed in 2011, and The Last Warlord: The Life and Legend of Dostum, the Afghan Warrior Who Led US Special Forces to Topple the Taliban Regime came out in 2013. “More than one hundred Uzbeks living in America came to Manhattan for the book signing,” Williams says. “They were thrilled.”

Beyond telling the full story behind Dostum’s involvement in the overthrow of the Taliban, Williams hopes that The Last Warlord might serve as something more: a model for conducting historical research that has political applications in the present.

“As scholars, we owe it to ourselves to be in the field. We should be traveling to these areas, even if it’s dangerous, and bring back these stories,” he says. “With the War on Terror, there are so many myths, so many misunderstandings. We can make blunders on a massive scale, so it’s important to make decisions based on history.”

Sandra Knisely ’09, MA’13 is the news content strategist for University Communications. Her passport stamps do not include Afghanistan.

Published in the Spring 2015 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.