Teaching Controversy

How can we prepare our kids to participate in the highly polarized world of politics?

THE STATE OF CIVICS EDUCATION

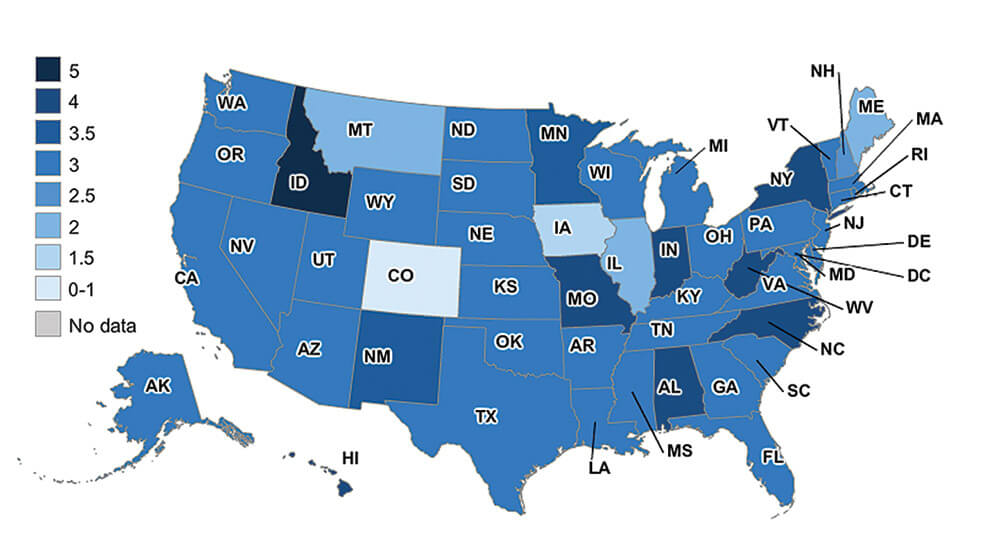

States require, on average, three credits of high school social studies for graduation. Credit requirements range from zero in Colorado to five in Idaho, according to the Center for Information & Research on Civics Learning and Engagement at Tufts University. Courtesy of Circle, Tufts University.

civ·ics \si-viks\ : the study of the rights and duties of citizens and of how government works

It’s a tough time for civics in America.

Resources are scarce. Schools focus their efforts on math and reading to prepare kids for high-stakes tests. And intense political polarization has made it riskier than ever for teachers to wade into controversy.

In the volatile months leading up to Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker winning a recall election in June 2012, principals in some schools in the state told teachers that they couldn’t discuss the historic event in their classrooms. At the same time, kids reported that their parents were getting into arguments at the grocery store and refusing to talk to family members due to disagreements about Walker’s decision to curb the power of state-employee labor unions.

Less than one-fourth of adults in the United States have political conversations with people they don’t agree with.

Source: Controversy in the Classroom: The Democratic Power of Discussion

What was happening outside the classroom was exactly why teachers should have been permitted to talk about the issues and competing views in school, says Diana Hess, a professor of curriculum and instruction in the UW’s School of Education. Hess, a former high school teacher, has done long-term research in three states, including Wisconsin, on how middle school and high school teachers engage students in lively and respectful discussions about tough issues.

Civic education without controversial issues is “like a symphony without sound,” Hess wrote in her 2009 book, Controversy in the Classroom: The Democratic Power of Discussion, which cemented her reputation as a national expert on the subject. Hess says the key argument for civic education is patriotic: the role of schools has long been to prepare people to participate in democracy (see Jefferson’s letter to Madison, quoted below).

“The challenge is that we need to prepare kids to participate in a highly partisan, polarized world, and yet, we need to do it in a nonpartisan way,” she says. “I call this the paradox of political education. And it’s really challenging.”

What do teachers need to make it work? Hess’s research shows that the answers are support from administrators and a high-quality curriculum, along with plenty of preparation time to guide students and make sure classroom discussions don’t degenerate into what we typically see on cable news programs.

“Above all things I hope the education of the common people will be attended to; convinced that on their good sense we may rely with the most security for the preservation of a due degree of liberty.”

Thomas Jefferson, in a 1787 letter to James Madison

At the UW, teaching controversy is a core component of teacher education. Shawn Healy ’97 used the techniques he learned in Hess’s methods class to get his students thinking and talking about important issues during his six years teaching social studies at high schools in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, and West Chicago, Illinois. Healy recognized that without any real meat for students to sink their teeth into, the subject would be stale.

“The extent to which we teach civics in this country — it tends to be pretty traditional. So there’s still a lot of lecture, a lot of textbook reading,” Healy says. “Believe it or not, there’s still even a lot of worksheet completion, and kids don’t like that. They don’t respond well to it.”

For the last nine years, Healy has been the civic learning and engagement scholar at the Robert R. McCormick Foundation in Chicago, where he leads the Democracy Schools initiative. Healy also advocates at the state and national levels for civic education that is student-centered, buoyed by his own experiences in the classroom and research by academics such as Hess.

In 2012, 68 percent of twelfth-graders reported studying politics, voting, or elections in school.

Source: U.S. Department of Education survey

“We’re all participants in our civic life of our country — this isn’t something you have to wait to do,” Healy says. “As a young person, there are plenty of opportunities even before you’re eligible to vote.”

A telling example comes from Adlai E. Stevenson High School, north of Chicago, one of twenty-two schools in Illinois that the McCormick Foundation has recognized as Democracy Schools for their commitment to civic learning. Students there got together to advocate for “Suffrage at 17,” state legislation that would allow seventeen-year-olds to register and vote in primary elections.

McCormick’s other Democracy Schools got involved, submitting electronic witness statements and testimony from around the state, and Stevenson students went to the state capitol in Springfield to lobby their legislators in person. The bill was passed into law and took effect at the beginning of this year. Students in Democracy Schools spearheaded a massive voter-registration drive, with more than nine thousand students in the Chicago area alone registering to vote in the spring primary election.

“To me, that’s a huge success story, and it’s what good civics looks like,” Healy says. “They’ll be lifelong participants in this process.”

Published in the Fall 2014 issue

Comments

Jackie johnson September 3, 2014

Correction: Colorado has a state law requiring one semester of civics for high school graduation– passed in 2003.