The Sounds of Aldo

Ecologists re-create the sound of a morning with Leopold.

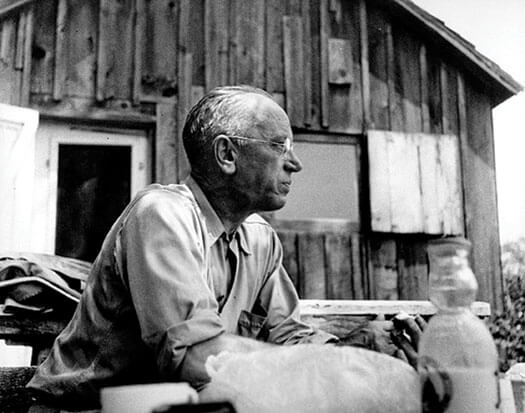

The world remembers Aldo Leopold as one of history’s great ecologists: a teacher, author, forester, and founder of the science of wildlife management. But the former UW professor was also a meticulous — almost compulsive — note-taker. His habit of jotting down data on early morning birdsong has enabled Stanley Temple and Chris Bocast PhDx’14 to re-create the soundscape Leopold woke to in 1940, even though the environment has changed significantly since his death.

Just as the term landscape refers to the totality of a place’s geography — its hills, valleys, forests, waterways, and buildings — a soundscape is a place’s total auditory experience: the compilation of the noises made by wind, water, birds, animals, people, and machinery.

In the 1940s, Leopold was working on a hypothesis that birds sing in response to daylight — that each species begins to sing when light reaches a certain brightness. To test the idea, he went to his shack in rural Sauk County, Wisconsin. In an era before tape recorders were available, he would wake before dawn, take his journal and a light meter outdoors, and write down the time and brightness when each species began to sing. He also noted the frequency of calls and where they came from.

Leopold died before he could publish the results of that study, but his journals were archived at the UW’s Steenbock Library.

Decades later, Temple, a UW professor of forest and wildlife ecology, examined those journals. He worked with Bocast, a graduate student at the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies and an audio engineer, to bring Leopold’s notes to life. Working with digital recordings of birdsong from Cornell University’s Lab of Ornithology, the two created the soundscape at Leopold’s shack on the morning of June 1, 1940. Each species of bird sings in the order Leopold recorded.

“I realized that he had done something that, as far as I know, no one else even attempted,” Temple says, “and that was to take detailed enough notes on the sounds that he was hearing that you could use them as a score to re-create that sound.”

The notes are so exact, in fact, that Bocast could use stereo recording to give an approximate location for each bird species.

“If you listen in stereo,” Temple says, “the birdsongs that come from the left are the birds associated with the fields and prairies. On the right are the birds associated with woods and forests. The birds in the middle are the birds associated with the edge between them.”

The area around Leopold’s shack is much different today than it was seven decades ago. There are fewer farms, and Interstate 90 runs nearby. As a result, the bird populations are different, and there’s much more human-generated noise. To get background sound that was free of the roar of cars and trucks, Temple and Bocast had to record wind and water at rural property that Temple owns near Mazomanie.

A five-minute selection of the soundscape is available online, and it has generated considerable interest.

“I think people are increasingly aware of how pervasive human-generated sound has become,” he says, “so it’s refreshing to be able to hear a more natural soundscape from the past.”

Published in the Spring 2013 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.