Wolves at the Door

The gray wolf has returned to Wisconsin in numbers greater than anyone had dreamed. UW faculty wonder how many wolves the state should have.

Once upon a time in Wisconsin, the big, bad wolf was an endangered species. Then he wasn’t. Then he was. Then he wasn’t. Then he was. Then not. Now he is. Again. And all in the last five years. It’s dizzying.

In the last generation, the gray wolf — or timber wolf, or Canis lupus, if you’re scientifically inclined — has made a remarkable comeback in Wisconsin. As recently as 1974, conventional wisdom held that our lupine population was zero. In 2009, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) estimated the count to fall between 626 and 662 — more, it turns out, than the state knows what to do with. Back when the DNR was formulating a wolf recovery plan, it set a goal of 350 to qualify the wolf as recovered. We’ve now passed that goal by more than 78 percent.

When Wisconsin’s wolf recovery is in the news these days, it’s usually in reference to the animals’ status with respect to the endangered species list. C. lupus has been included on that roll since the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service distributed its first list in 1974, a year after Congress passed the Endangered Species Act. Since 2005, when the state’s wolf population topped 350, the DNR has been encouraging the federal government to delist C. lupus, but it has repeatedly been overturned by legal action, led (at least in the latest round) by the Humane Society of the United States.

As the administrative and legal battle over wolves’ status shows, Wisconsin is having a hard time figuring out what to think of its growing population of predators. While interest groups argue over what the state’s optimal number of wolves should be — or even if there is one — UW faculty see the animals’ return as an opportunity to study the interaction of a wild species in a modern environment.

How Many Is Enough?

“How fantastic to see a keystone predator return to Wisconsin,” says UW-Madison geography professor Lisa Naughton ’85, MS’87. The state, she notes, offers little actual wilderness. It’s a “mixed-use landscape,” she says, meaning that it’s largely dominated by human activity: agriculture, and small towns, as well as a few forests and bogs, all intersected and connected by a loose network of roads.

“Most of the world increasingly resembles Wisconsin in terms of human-dominated landscape,” she says. “That’s what makes [the wolf recovery] so exciting, so interesting, and so important.”

But, she knows, not everyone feels that way.

There is, for instance, Scott Meyer.

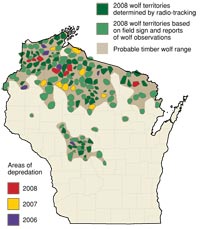

Wolves are now established in northern and central Wisconsin, but as they’ve spread, so has conflict. The purple, yellow, and red areas mark reports of wolf attacks on domestic animals. Map: Wisconsin DNR/Jane Wiedenhoeft and Drew Feldkirchner

In 2001, Meyer was hunting bobcats near Pelican Lake, east of Rhinelander, with a redbone hound named Bonnie. Meyer had raised Bonnie for twelve years, spending “hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of hours” training her, but that all came to naught when the two were separated by a river and Bonnie found not a bobcat but a wolf.

“This was a relocated problem wolf that had been killing deer on a deer farm,” Meyer says. The DNR had moved it to the Pelican Lake area, but Meyer was unprepared to find it because, he says, officials didn’t inform the county. “I’ve always had a contention about that.”

By the time Meyer caught up with Bonnie, the hound was dead and partially eaten. “It was a horrific sight,” he says.

Meyer is convinced that Wisconsin has more than enough wolves — more, even, than the DNR says it has, and he’d like to see the state take action to control and reduce its population.

Howard Goldman MA’71, however, fears government is too ready to reduce the number of wolves. Goldman is the Humane Society of the United States’ state director for Minnesota, and he’s convinced there aren’t nearly enough wolves. That’s why the Humane Society has gone to court repeatedly to keep the animals on the endangered species list.

“We’ve argued successfully before federal courts that the wolf is not, in fact, recovered,” he says. “The Endangered Species Act states ‘a species which is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range’ is endangered. The [gray] wolf presently occupies only 5 percent of its historical range. Until the wolf is fully recovered, it should remain federally protected.”

Naughton is familiar with stories like Meyer’s and with opinions like Goldman’s. She and her husband, assistant professor Adrian Treves of the UW’s Gaylord Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, formed the Living with Wolves project, an effort, she says, “to find a fair and ecologically sustainable approach to coexistence” with wolves. Part of that project’s work is listening to the various arguments and gauging the state’s public opinion about wolves.

Their work touches on a concept called social carrying capacity. Carrying capacity is an ecological term for the number of a given species that an ecosystem can sustainably support. Social carrying capacity, however, refers to the number of a species that people feel is appropriate.

“One really looks at two questions,” Treves says. “First, what’s the carrying capacity, which we think is somewhere between five hundred and seven hundred [wolves]. But second, is that tolerable? Will people who live in areas where wolves are active put up with that many over the long term?”

Treves and Naughton have conducted surveys of Wisconsin citizens since 2001 to measure their feelings about the growing wolf presence. They’ve read reports and complaints from people who have suffered wolf depredation, and they’ve attended public meetings where people have aired grievances — and occasionally support — about DNR wolf policies.

While Naughton says that the public meetings tend to be dominated by those who feel there are too many wolves (“Even in Madison,” she says, “where I was certain that wolf huggers would come out in force, the mood was solidly against them”), she says that overall, there’s widespread support for the animals.

“Most Wisconsin citizens want at least some wolf presence in the state,” she says. “But those who feel strongly, at either end of the spectrum, drive the argument.”

This has left Treves and Naughton open to angry late-night calls from political partisans. Still, they say their work is coming closer to its goal of defining a “fair and ecologically sustainable” wolf policy — and one that is increasingly tolerant of wolves.

“When the DNR set that 350 level, it was kind of pulling a number out of a hat,” Treves says. “No one had really done any research to see what the state’s carrying capacity or public tolerance was. But they actually did a pretty good job. When we did our first surveys in 2001, we found that [about] 350 was the tolerance level. But our more recent surveys are showing a higher number — one that falls closer to 500.”

On the hunt: DNR pilots follow radio signals to track wolves from the air. Though easy to spot against winter snow, the animals are virtually invisible in summer. Photo: Wolfgang Hoffmann

But he warns that this tolerance might not be entirely sustainable. Much of Wisconsin’s acceptance for wolves is based on the fact that the DNR reimburses those who have suffered wolf depredation, and the cost of those payments is rising. According to Adrian Wydeven, head of the DNR’s wolf recovery program, the state sets aside about $35,000 a year for wolf compensation — 3 percent of the amount that Wisconsin citizens pay when they purchase endangered resources license plates for their cars. But the actual costs have run much higher — $101,000 in the 2008–09 fiscal year. Hunting hounds like Meyer’s account for nearly half that total, some $48,250.

But while the reimbursements weigh down the DNR’s budget, they provide little solace to those who’ve suffered from depredation.

“Compensation is the last of your worries,” says Meyer, even if the loss is livestock. When it’s a hound like Bonnie, “it’s like losing a member of your family. They’re confidants, companions, buddies.”

Balancing the costs of wolves, however, are unexpected benefits. As wolves return to Wisconsin, they may be having a broad effect on the state’s ecology. UW-Madison botany professor Don Waller and others have been studying plant life in areas where wolf packs are active, and he believes they’re finding evidence that wolves’ predatory presence may have beneficial effects on plant life. Landscapes with wolves seem to support more diverse plant communities than similar areas without wolves. They do this, he thinks, through their effect on the deer population, both in number and behavior.

“Wolves have two kinds of effects,” Waller says. “First, there’s the numerical effect: wolves eat some deer, decreasing their density. But there’s also a less direct effect: wolves create an ecology of fear among deer. When predators are present, deer don’t just feed lazily. Instead, they get skittish, move more, and overgraze less.”

For scientists like Waller, who feel that the state’s large deer population has damaged diversity in general, wolves may be a biological boon. Waller notes that this agrees with the writings of Aldo Leopold, founder of the UW’s department of wildlife ecology. In his seminal essay “Thinking Like a Mountain,” Leopold wrote that, “while a buck pulled down by wolves can be replaced in two or three years, a range pulled down by too many deer may fail of replacement in as many decades.” But hunters who prefer plentiful deer are less impressed.

Again, it leaves the question: are wolves protected enough, or are they too protected? The issue of whether wolves remain on the endangered species list, Naughton and Treves worry, has the potential to cut into and even reduce support for wolves around the state.

“There’s a real and growing difference among people who feel strongly about having wolves in the state,” says Naughton. “On the one hand, there are those who are interested in ecosystems and biodiversity, who would like to see decisions made for the good of the species as a whole. And on the other are animal rights groups, which would like to protect every individual wolf.”

As that difference grows, the Living with Wolves project is working to bring the various parties to an understanding. “Wolves have recovered beyond our expectations,” says Naughton. “But now comes the hard part — how do we live with them?”

Numbers Game

Irrespective of whether Wisconsin’s citizens feel the state has too many wolves or not enough, the more intriguing question to Tim Van Deelen, an assistant professor of wildlife ecology at UW-Madison, is finding out how fast wolves can reproduce and spread. To that end, he’s been following the rising numbers reported by the DNR and trying to come up with mathematical models. But to make an educated guess about how many wolves there will be, it helps to have an accurate count of how many there are. And that number is surprisingly well documented.

Once upon a time, Wisconsin’s social carrying capacity for wolves was zero.

In the nineteenth century, C. lupus was abundant in the Midwest, but it was looked upon at best as a nuisance and at worst as a public danger. In 1865, the state began to offer hunters a bounty — initially $5 — for each wolf carcass they brought in. That bounty wasn’t repealed until 1957, shortly before wolves were extirpated. Although the DNR received occasional reports of lone wolves in remote regions, official opinion held that none made a permanent home here. Only about seven hundred wild wolves remained in the entire Midwest — all in Minnesota, where the forests were more remote, or in Isle Royale National Park in Lake Superior.

But things began to change after the passage of the Endangered Species Act. Once freed from danger, the number of gray wolves began to grow, and the Minnesota population started — slowly — to expand into the animal’s former territory, crossing into Wisconsin.

By 1980, the DNR estimated that there were between twenty-five and twenty-eight wolves in Wisconsin, most of them distributed among five packs in the northwest. And then the DNR did something very wise: it started a program of trapping wolves, attaching a radio collar to them, and monitoring their movements in the wild.

This program has continued over the last thirty years. Each spring, teams go out to trap wolves, attempting to catch and attach a radio collar to at least one adult animal in 15 to 20 percent of the state’s packs. Hundreds have been collared over the years, enabling the DNR to track wolves from the air year-round. Every month, DNR pilots take off, armed with a radio telemetry receiver and a global positioning system (GPS) device to find and record the location of dozens of wolves. Though the animals are nearly invisible from the air in summer — when the trees are in full leaf and the animals’ heather-colored coats blend into the landscape — pilots have a chance to spot and count wolves in the winter, or to direct DNR staff or volunteers on where to find them. The result has been a three-decade accounting of the wolf’s progress across the state.

“It’s an amazing data set,” says David Mladenoff ’73, MS’79, PhD’85, a UW-Madison professor of forest ecology. “Wisconsin was really smart to start [radio collaring] early on.”

Those data show that wolf populations remained fairly constant throughout the 1980s, but began showing signs of growth in 1990. But what that growth meant was open to interpretation. The federal government’s wolf recovery program set a goal of eighty animals for three consecutive years in Wisconsin and Michigan — meet that target and wolves would be upgraded from endangered to threatened. Get the number to a hundred, and wolves would be delisted altogether. In 1999, the DNR developed a state management plan with a goal of 250 wolves in Wisconsin before the animals would be removed from the state’s list of threatened species, and a long-term management goal of 350.

“At the time, this was fairly academic,” says Van Deelen. “In the 1990s, no one believed we’d ever see 350 wolves here.”

But the numbers continued to grow. The wolf population reached eighty for the first time in 1995, and it topped a hundred the next year. By 2003, it surged past 350 and continued rising. Today’s DNR estimate of between 626 and 662 is up 14 percent from last year’s. There are some 162 packs spread out across the northern and central parts of the state, and as many as 200 cubs may be born this year. Though many of them will die, enough will likely survive to continue growth.

The data have also taught ecologists a lot about what wolf habitat looks like.

“We used to think that wolves needed real wilderness areas to survive,” Mladenoff says. “But that’s not true. All they needed was a place where there’s enough prey (which in the Midwest would be white-tailed deer) and where people wouldn’t kill them, either deliberately or accidentally. Then they can get by almost anywhere.”

Still, wolves seem to like some geographic characteristics better than others, and Mladenoff has compiled those and mapped them in an effort to predict where wolf packs will become established. The single attribute that appears to attract wolves most is a lack of roads, which implies a lower level of human activity.

“Road density seems to be the key,” he says. “Of course, it’s not like wolves know this. They’re figuring it out by trial and error. They survive in some places and don’t in others, and they stay where they survive.”

So how many wolves can the state support? Both Mladenoff and Van Deelen suspect that the days of rapid multiplication may be coming to an end. As the number of wolves and packs has grown in recent years, they’ve filled up all of the best — that is, least road-dense — lands.

“If you look at the habitat wolves currently occupy, it’s not all good quality,” says Mladenoff. And in the poorer-quality areas, the wolf population “probably isn’t sustainable.”

Van Deelen used Mladenoff’s habitat research in his population models, and he concludes that the boom is near an end.

“If you look at the data, you see that there’s almost no support for continued exponential growth,” he says. Looking at wolf populations in the entire territory south of Lake Superior — Wisconsin and Michigan, primarily — he concludes that the carrying capacity for the entire region is only about 1,300 wolves, split roughly evenly between the two states.

That puts Wisconsin’s wolf carrying capacity at about the current level — though Van Deelen admits his calculations are far from iron-clad. “The trouble is that there are relatively few data points at recent, high-level density,” he says, meaning that it’s difficult to generalize from a few years and a few hundred wolves.

Still, the data on wolf expansion offer some insight on the animal’s ability to thrive. In fact, with so much available food — that is, with so many available deer — Van Deelen’s calculations

suggest that wolves could reproduce at such a rate that they could withstand a hunt that culled up to 30 percent a year.

But he doesn’t recommend such action. Instead, he’d rather see the animals prove his calculations right or wrong. “I’d kind of like to see nature take its course,” he says. “I’d like to see what [population] level they arrive at on their own.”

Mladenoff is concerned, though, about how increasing wolf numbers might affect state politics. “I think, from a wolf standpoint, they’re fine with continuing to expand,” he says. “But there’s definitely more conflict [between wolves and people] happening. There’s been a lot of popular support for wolves over the last decade or so. But there’s a danger of a backlash as we have more conflict.”

Epilogue: Where Wolf?

I am, I suppose, part of the problem. All my opinions about wolves are based on either emotion (as Naughton says, “Wolves are laden with symbolism. There’s something about them that stirs the passions — they’re the quintessential wild animal”) or personal experience. Since I’ve never seen a wild wolf in Wisconsin, I have a hard time thinking of them as anything but scarce. So I went to see Phil Miller.

Miller is a pilot with the DNR, and part of his job is to fly out, once a month or so, in a single-engine, four-seat Cessna airplane to find wolves. He cruises along at a thousand feet above the northwestern part of the state to plot the locations of collared animals.

On a muggy morning in mid-June, Miller took me up into the sky to hunt for wolves. He had a list of a dozen to check up on, and over the course of two and a half hours, we managed to track almost all of them down. But as it was summer, we didn’t actually see a single Wisconsin wolf, though we spotted one of Miller’s targets jogging alone down a red-clay road in Minnesota.

Otherwise, we had no visual evidence of wolves in Wisconsin — until the last animal we checked up on.

In a partially cleared pine wood southwest of Solon Springs, Miller saw a circle of sand with a hole at one end, and the beep was coming straight from the hole.

“I think we’ve got a den,” Miller said. “It’s definitely a den — and there’s a pup standing in it.”

We circled several times, dropping lower on each pass so that Miller could be certain of his sighting before heading away. We left with visual proof of another generation to add to Wisconsin’s lupine population.

But what will become of that generation is still up in the air.

Published in the Fall 2009 issue

Comments

Kevin Coffey February 27, 2012

“UW faculty wonder how many wolves the state should have.”

Of course! Does the UW faculty wonder how many humans the state should have?

Human arrogance!

mike Hansen March 9, 2012

I live in Northern Door County, in Fish Creek Wisconsin. I wanted to share the exhilarating experience that I had while walking on Spring Road, south of Wandering Rd. Within 20-30 yards of my presence, I observed what “had to be a wolf” crossing the road, ahead of me. I am in no way stating that I am 100% sure that it was a wolf vs. a coyote. However, the size of this animal , swayed my opinion to believe that it was, in fact, a wolf. (color was mostly gray with tinges of brown on the torso.) General physique described as large, tall, and lanky. Time frame of this observation was around 5 p.m.

Respectfully

Mike Hansen

Robert Goldman June 16, 2012

Wisconsin is so lucky to have a healthy and thriving wolf population. It means that your ecology is healthier and getting more so. And having lots of wolves says good things about the majority of people there who respect and protect the right of wildlife to be on this Earth where they belong just as we do. Don’t let the wolf haters and ignorant demonizers change that. Respect and protect the wolves and other native wildlife there and both you and your land will be blessed with good health and a good spirit. Many of us are working and hoping to welcome wolves back to Maine where they belong. There’s lots of forests and lots of prey for wolves in Maine but the rednecks here are brutal and have little respect for wild nature and a healthy ecology. Wolves are amazing, native and vital natural predators. Protect them and be blessed.

Ron October 9, 2012

That’s right, we have a healthy wolf population, that’s why I will be out there hunting them (with a friend of mine who holds a wolf tag) I am going to film the hunt. I can’t wait, to be a part of this. Most people who love the wolves live in the city where they don’t have to deal with them. Move into wolf country, buy some livestock, dogs, cats, chickens, horses etc…, then report back and let us know how that works out for ya. see if you like them then.

Joe October 25, 2012

Ron,

I live in the Northwoods. I moved here FOR the nature. The animals were here first. If you don’t like living with wild animals,, then MOVE. I am not against hunting. I AM against hunting wolves. It serves no purpose. I’ve never heard of wolf burgers or wolf steak (I am a meat lover btw). Who are we as humans, to “manage” a population of wolves,, when we can’t even manage our own population. I’ve honestly been sick since October 15th.

Peter December 16, 2012

Thanks Kevin! Yes, how many humans should this state have? Compared to stupid humans. Unfortunately Darwin’s law is no longer in place.

Kurt Wood January 19, 2013

Wolves are wild predators and when the deer, grouse, pheasant and turkey are gone where will the state and the DNR get the millions of dollars hunters spend every year on hunting in our beautiful state. When the livestock and our pets are gone then I guess we will feed them our kids. I would like to take these “nature lovers” camping and hiking and see how much love they feel for the animal when it is stalking them. Is it really the farmers and their neighbors that live and work in the country that are ignorant? We are at the top of the food chain for a reason. We are humans. SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST IS A LAW OF NATURE.

Ben January 23, 2013

Kurt,

You bring up an excellent point by describing Wisconsin as a beautiful state, and I cannot agree with you more. But how do you think it developed into the landscape that it did? It was not through human intervention; it was through thousands and thousands of years of naturally occurring processes. The deer, grouse, pheasant, and turkey species obviously survived that time – with a much greater wolf population. According to the Wisconsin DNR, vehicles and hunters kill about 2x and 21x more deer than wolves, respectfully. If you are that concerned with the deer population, I suggest you aim your efforts at the population’s other pressures. Here is the link for that DNR information:

http://dnr.wi.gov/topic/wildlifehabitat/wolf/facts.html#Misconceptions

It is true that survival of the fittest is a law of nature, but how natural was it for you to write that post on a computer within the heated confines of your home while snacking on some store-bought food? Hunting with guns and trapping animals without compassion is not natural. My point: humans are not part of the “natural” cycle as we think of it due to our technology.

And it seems that you care about game species of Wisconsin – you should be thrilled to hear that biodiversity is increasing! Biodiversity is closely linked to ecosystem health. Wolves are a keystone species and they keep many other species in check; this not only includes your beloved game species, but also mesopredators like coyotes, foxes, etc. I understand that living with wolves might cause concern, but please read up on research about them and about ecosystem health. Please do not make emotion-based arguments – they do not facilitate conversations and only persuade those who cannot think for themselves. I can assure you that wolves are worth the “risk.”

Jesse Krizan April 1, 2013

Ben I couldn’t help but notice you referred to some as sitting at home eating store-bought food but many of us hunt for the food we put on our tables! We eat venison, grouse, turkey, duck, pheasant, goose etc. 365 days a year. I make a extra fund profit off the furs I sell from trapping and hunting that I put into my family fund and improvements on my living stature etc. If you think most people hunt for just the “rack” or just a “trophy” in general your wrong. I know more hunters in my area that hunt for the right reason than ones that don’t. We are a more educated species of animal so to speak. Wild animals aren’t as mind tolerant as we are. They aren’t capable of doing the things humans can. So were not supposed to be the best we can be just cause animals can’t? That’s being pretty biased and naive in itself. Its the people that haven’t lost $12,000 in profit due to wolves, or lost a once in a life time companion to wolves, ones who don’t have to deal with them day in and day out that try to make this argument of they are better than they are anything else. I hunt up north along with quite few other people I know well from the area hunt up in Northern Wisconsin and if you’ve seen just the number of deer that just are not there any more you’d get a full effective realization of whats going on! Before the wolves became highly popular we could deer hunt all 9 days and get atleast 2 deer and see 2 dozen. now were lucky to see 8 deer all season but we do see about 32 wolves. Are you trying to argue your point of this problem from your enclosed, warm home as well? I’m quite sure you are. That’s not even a conversation point at all. That’s plain out a stupid comment to even be made. If you’ve had multiple damage done to your profit cause of wolves and still feel strongly on their existence I’d like to hear your points on it. If not I really don’t feel you’ve got a reason to want them around.

Northern Chelle August 29, 2013

http://www.weau.com/home/headlines/NEW-INFORMATION-Wolf-which-likely-attacked-teen-negative-on-rabies-221688511.html

This is the only argument one needs against wolves in Wisconsin. Next we’ll be finding small children mangled like the hunting dogs.

Northern Chelle August 29, 2013

I’m just wondering…as I have been for years why none of the “experts” on wildlife, biology, and management saw this in our future like I did.

Northern Chelle August 29, 2013

Scroll to the bottom of this page to see excellent photos of wolf kills in Montana… and then tell me how you feel about taking your kids camping and hiking this weekend.

http://www.stormfront.org/forum/t910792-3/#post10577726

Anthony Giammona October 12, 2013

We all need help protect are natural resources more than ever here in wisconsin. We are under attack from outside powers that be and their inside political monkeys like Scott Walker who’s ONLY MOTIVE IS TO PROFIT THEM.

“GOD BLESS WISCONSIN”

Northern Bob October 18, 2013

@Anthony Giammona

You sir are an idiot. Maybe if you did some basic research you would find that Walker asked for legislation banning night hunting of wolves (http://www.twincities.com/ci_22834179/wisconsin-walkers-budget-would-end-night-wolf-hunting) which is a good step in the right direction for wolf advocates. On the other hand the population of all state animals needs to stay in balance and we do that with hunting. As a veteran hunter living in the north motor vehicle fatalities and accidents has significantly dropped due to hunting activity. So before you use this forum to do nothing than bash Scott Walker, who has done a tremendous amount of good for our state, maybe think before you speak and backup your random, off base rants with some real information.

Northern Bob

Marsha October 27, 2013

I’m proud to know that the state that is my birthplace has had the eco-sensitivity to have allowed and aided the return of a majestic animal.

I now live in the North East where the wolf has been hunted to extinction. The result is not only the loss of this proud animal but the disruption of the natural balance of predator and prey. Mesopredators such as coyotes have replaced the wolf here to become the top predator in the food chain. This has become as much of a threat to wild, domestic, & human animal alike as any wolf. Whereas the wolf would generally avoid human contact the coyotes doesn’t. This is not a problem that nature created, but one that man has. NOW here in the NE they discuss how to rid us of the threat of coyotes–once the coyote is gone what will be considered the next threat, one wonders?

I’m not an extremist, but one that respects nature and what it offers us. But just a thought: the last time I saw a dead deer, bobcat, turkey, dog, or cat it was on the road an obvious victim of human intervention, not that of a wolf or the coyote.

Jason November 1, 2013

How can anyone justify bringing in more wolves when pets are being killed, farmer’s sheep/cattle (any farm animal for that matter) getting killed? People living in the north woods don’t even feel safe to walk in the woods anymore without a form of protection. Do you feel safe having your kids play in the woods? Before you answer, do you live in the north woods where wolves are prevalent? Someone had answered, well we are at the top of the food chain but not naturally, but only because of technology. Yes! But we are smart and need the feeling of security and safety so we do what we can to feel that way, guns etc… So having everything natural, we want to bring in an animal that could stalk us and eat us for dinner if we lived in the wild together??? Wolves are good… makes no sense.

Anne November 4, 2013

To Jason –

Wolves are not being ‘brought in’ – they re-established on their own from populations in Minnesota & probably Upper Michigan in the late 50s-early 60s. People like you are the reason why so many others are afraid of nature by spouting your inane crying ‘wolf’ stories, and why there is so much fear-mongering about wolves and other large predators. Humans don’t like large predators primarily because they compete with us for big hunting trophies (i.e. deer with huge racks). Granted there are those who compete for food, and may have problem wolves attacking livestock (but bears, weasels, bobcats, coyotes, and feral pets do that too) but that is a minority group. How many human-wolf attacks have you heard of in the last several decades? From my research on this topic, there have been no human-wolf attacks recorded here lately, and not many overall. Coyote attacks on humans are a lot more common. And yes, I do live in wolf habitat and I am much more afraid of other humans than of our native predators – I have had a few encounters with bears and wolves, and each time it was a matter of them being curious as to what I was. By the way I also hold a degree in wildlife management, so I do kind of know what I am talking about.

Dev December 6, 2013

Why should anyone be worrying about what the animals are doing? I simply think people should worry about what current problems they have already to deal with. So what if an animal killed your livestock or hunting dog? They are trying to survive in the world that is today. Little did people know, but we are living on what used to be the wolves hunting grounds and homes. It’s our fault. Not theirs.

~ Dev

Tag December 8, 2013

There was a reason for the great decline in the wolf population and that is because our forefathers that settled this state knew that if man was to have his way in the state (such as raising a family without fear of a wolf eating your 5 year old son, or losing half your cattle to a wolf attack)the wolf had to go. wolves don’t just kill their victims they cripple them then start to eat them while they are still alive. I do not mind having a few wolves but when they start to attack livestock and people they need to go. I have a 3 month old son and when he is 3 I don’t want to be worrying that a wolf might get him just because he ran outside to play. As a Wisconsinite if a few wolves want to live here that is fine but if they become a pest such as if they worry the safety of my family they need to be hunted till the threat is no more even if that means extinction (hey, if its going to be any issue of it being me or them I want it to be them not me who has to go). I love living in the Great State Of Wisconsin was born and raised here and hope to raise my family here also without the fear of wolves.

Ashley Flick December 18, 2013

I love that WI wolves are in the spotlight… Im an Eau Claire native 21, but spent over half of my life between the Colfax, Wheeler area, I grew up on a tree farm which had its share of critters, Like a pack of coyotes at our nightly fires were no big deal, I’ve seen bear, deer, badgers, ect on our property (which was 300 acres of a tree farm) but on special nights the howls were something different, they were immaculate, they were close and B-E-A-utiful!!! MY dad, husky, and I would howl back. I’ve only seen 2 in my life and they were loners, about 20 feet away i wish i had a camera but the mental image will never fade. They are beautiful, luggourious, gifts of nature and I feel building up is raping them of that. I understand population control, but of the 200 and something beauties and over half were hunted in 2013 isn’t right. I’d love to work with them… get up close and personal I’ve had a knack, thing, understanding for them my whole life. I understand and consider everyones point of view but my initial concern and love goes for these mis-under stood fuzzy, lickie, un-socialized dogs. Let us all give nature a chance and see the good it brings out in us.

JAN MARIE June 7, 2014

THANK YOU SO MUCH, JOE, FOR YOUR COMMENT. I HAVE BEEN SICK TOO. INDEED, WHO ARE WE TO TRY TO MANAGE ANY OTHER SPECIES WHEN WE CANNOT MANAGE ONE DAY IN OUR LIVES WITHOUT GREED AND EVIL, MURDERING, CANNOT MANAGE ONE DAY WITHOUT ADDICTIONS THAT BRING DOWN OUR SOCIETY AND HARM OTHERS, ESPECIALLY CHILDREN. YOU ARE SO RIGHT AND THANK YOU SO MUCH FOR SPEAKING UP!

JAN MARIE June 7, 2014

THANK YOU JOE, FOR YOUR COMMENT. I HAVE BEEN TRULY SICK TOO WITH ALL THE CRUEL TRAPPING AND HUNTING. WHO ARE WE INDEED TO TRY TO MANAGE ANY OTHER SPECIES WHEN OURS IS SO WEAK AND MIS MANAGED. WE HUMANS ARE STUPID AND CRUEL. WE DO NOT PROTECT OUR OWN CHILDREN SO WHY WOULD PEOPLE LIKE THE MAN WHO WROTE ABOUT WANTING TO HUNT BECAUSE WOLVES WERE WRECKING HIS LIFE PROTECT A WOLF. THESE PEOPLE ARE MENTIONED BY GARRISON KEILLOR AS BEING JACK PINE SAVAGES. AMEN!!!

Dan Kringle August 5, 2014

Dear Mr. Scott Meyer, Wisconsin needs less humans, not less wolves.

Adam Kramer September 15, 2014

I think there should be an equilibrium between the population of the predator and the prey. This being said, Not all wolves should be exterminated. some are needed to further refine the population of deer in Wisconsin. There are several ways we could go about limiting the population of wolves in good ol’ Wisco. We could give out wolf hunting permits, but limit the amount of permits we can give out. We can also put into effect an adjustable bag limit to allow growth and restraint on the population as needed.

demetrey .jkb. winterstone September 15, 2014

The most important events in the chronology have been essentially unpredictable. In 1980 the wolf population crashed when humans inadvertently introduced a disease, canine-parvovirus. In 1996, the moose population collapsed during the most severe winter on record and an unexpected outbreak of moose ticks. In the late 1990s, intense levels of inbreeding among wolves were mitigated when a wolf immigrated from Canada. In response, the wolf population generally increased throughout the early 21st century, despite declining moose abundance.

Michael Rosekrans October 4, 2014

This is a very well written article, however I believe that there was not enough emphasis placed upon the cascading effect a keystone predator like the wolf has on plant populations. Deer heavily overgraze native plant vegetation allowing other non-native species to take over. Wolves keep over-grazing deer in balance strengthening the plant community, which in turn reduces erosion and runoff into rivers and lakes. Wolves also reduce Coyote numbers, which in turn increase food sources for hawks, owls and other predators. Hunters should also know that wolves actually help the deer in the state by attacking the old, sick, and the weak. It wouldn’t make any sense to attack a strong buck in its prime. This leaves the strongest deer to reproduce strengthening the gene pool. I also noticed many comments about “nature lovers” going hiking and being stalked by wolves and that most of these supporters are from the cities. I have camped, hiked, backpacked and lived in wolf country for the better part of the last three years and have never had a negative confrontation with a wolf. For the past two summers I have been a backpacking guide in Yellowstone National Park. In one instance on a solo day hike I approached a mountain saddle and a wolf appeared. I assumed that it had a den nearby. As I approached, the wolf paced back and forth barking at me but never approaching. As soon as I turned around it stopped barking and returned to its den. In 500 + miles of hiking in wolf country in the northern Rocky Mountains I never felt in the least bit threatened by wolves. In Wisconsin the most dangerous animal to humans in the wild other than humans themselves are ticks, Causing far more injuries and disease than wolves, not to mention the impact they have on domestic pets. It seems unfair then to wage war on wolves because of one instance with a domestic dog when deer ticks have caused much more damage. May I note that according to the wolf almanac there has never been a documented case of a healthy wolf attacking a human. I am a Wisconsin native and have had the pleasure of seeing wolves in the wild on several occasions. There is not a more majestic animal or better symbol of the wilderness. Wolves will always be an area of controversy. They require a lot of wild land which the state of Wisconsin does not have, so there will always be cattle and domestic pet conflicts. In the time wolves have been absent from the state human population has steadily increased as well as the deer population leaving an abundance of food and a lack of land. There is also an extreme lack of education on the topic. Wolf management plans are being put in place by the DNR that most of the public have not seen, do not know how to access, and most of all do not know exsists. The solution with the wolf debate does not lie in management plans, which are heavily influenced by uneducated public opinions. The solution lies in scientific study and education and until there is funding for such projects and education on the truth about keystone predators this debate will continue, livestock and domestic pets will be killed, and wolves will be unnecessarily shot, hunted and persecuted.

Michael Rosekrans October 4, 2014

This is a very well written article, however I believe that there was not enough emphasis placed upon the cascading effect a keystone predator like the wolf has on plant populations. Deer heavily overgraze native plant vegetation allowing other non-native species to take over. Wolves keep over-grazing deer in balance strengthening the plant community, which in turn reduces erosion and runoff into rivers and lakes. Wolves also reduce Coyote numbers, which in turn increase food sources for hawks, owls and other predators. Hunters should also know that wolves actually help the deer in the state by attacking the old, sick, and the weak. It wouldn’t make any sense to attack a strong buck in its prime. This leaves the strongest deer to reproduce strengthening the gene pool. I also noticed many comments about “nature lovers” going hiking and being stalked by wolves and that most of these supporters are from the cities. I have camped, hiked, backpacked and lived in wolf country for the better part of the last three years and have never had a negative confrontation with a wolf. For the past two summers I have been a backpacking guide in Yellowstone National Park. In one instance on a solo day hike I approached a mountain saddle and a wolf appeared. I assumed that it had a den nearby. As I approached, the wolf paced back and forth barking at me but never approaching. As soon as I turned around it stopped barking and returned to its den. In 500 + miles of hiking in wolf country in the northern Rocky Mountains I never felt in the least bit threatened by wolves. In Wisconsin the most dangerous animal to humans in the wild other than humans themselves are ticks, Causing far more injuries and disease than wolves, not to mention the impact they have on domestic pets. It seems unfair then to wage war on wolves because of one instance with a domestic dog when deer ticks have caused much more damage. May I note that according to the wolf almanac there has never been a documented case of a healthy wolf attacking a human. I am a Wisconsin native and have had the pleasure of seeing wolves in the wild on several occasions. There is not a more majestic animal or better symbol of the wilderness. Wolves will always be an area of controversy. They require a lot of wild land which the state of Wisconsin does not have, so there will always be cattle and domestic pet conflicts. In the time wolves have been absent from the state human population has steadily increased as well as the deer population leaving an abundance of food and a lack of land. There is also an extreme lack of education on the topic. Wolf management plans are being put in place by the DNR that most of the public have not seen, do not know how to access, and most of all do not know exists. The solution with the wolf debate does not lie in management plans, which are heavily influenced by uneducated public opinions. The solution lies in scientific study and education and until there is funding for such projects and education on the truth about keystone predators this debate will continue, livestock and domestic pets will be killed, and wolves will be unnecessarily shot, hunted and persecuted.