Staying Power

Don’t write off newspapers, Phil Rosenthal says, urging skeptics to recognize the adaptability they’ve demonstrated over the decades.

This Chicago Tribune columnist covers his very own industry, and he maintains that reports of the demise of newspapers don’t tell the whole story.

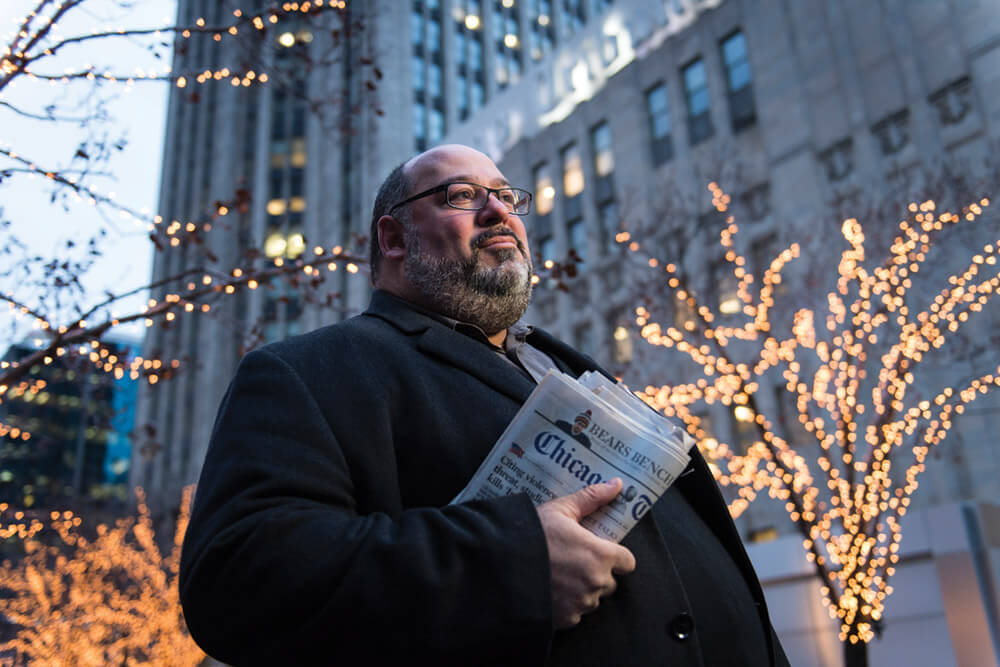

Phil Rosenthal ’85 is holding an endangered artifact. Its size and shape have evolved over time, yet its benefit to society, he argues, remains the same — even after TV and radio threatened to steal away audiences and advertisers. Even after the Internet actually did.

The artifact Rosenthal holds is a newspaper. He picks it up off his desk in a cramped back office at the Chicago Tribune, and admires a front page that still demonstrates all the journalistic ideals he was drawn to as a UW–Madison freshman in the early 1980s, a time when he regularly pestered an editor at the Capital Times, hoping to land an assignment.

Rosenthal eventually convinced editors at the former afternoon daily to give him bylines. He made lasting impressions on professors at the journalism school, then landed high-profile jobs at the Los Angeles Daily News and the Chicago Sun-Times. But after more than thirty years in the newspaper business — covering grisly crime scenes as a news reporter, scribbling in a notebook at UCLA and LA Rams games, and, with a TV column, helping nudge Jay Leno to do something Leno had long resisted — Rosenthal finds himself in the midst of his biggest career challenge yet.

The Internet has grabbed hold of today’s news consumers, who, as evidenced in dramatically declining advertising revenue and newspaper subscription numbers, are decidedly less interested in the smudge of newsprint on their fingers. In turn, newspapers across the country have been forced to close, slash staff, eliminate local movie reviews and other staples, and, in some cases, abandon the print product altogether in favor of online publications.

It’s a quandary Rosenthal deals with both personally and professionally. Now a business columnist at the Chicago Tribune, he joins his colleagues in worrying about his employer’s future. He may have gone into journalism partly because of a belief in its mission to inform and improve lives. But today he has a house in Chicago, a wife who also works, and two children in grade school. Rosenthal’s love for journalism also has to pay the bills.

Complicating matters is the fact that media news and the happenings at the Chicago Tribune — a historic and major corporation in the Windy City — are part of his beat. So Rosenthal must regularly write about the state of the industry in which he works and the company that provides his paychecks. The duty, which he describes as “walking a tightrope,” forces him to confront his bosses about their business decisions and reveal to the public flaws in the very industry he hopes they’ll continue to support.

“I’d be lying if I didn’t admit I’m aware of the impact of every single word when I write about the Tribune — probably more than when I write about other companies,” Rosenthal wrote in a June 2006 column published just before the Tribune Company was sold in a controversial transaction with ramifications that would play out for years afterward. He echoed the sentiment last summer, weeks after his front-page byline helped to explain a high-stakes move that broke the company into two entities: one primarily for broadcast endeavors, the other for print publications.

Interestingly, though, Rosenthal says the front-row seat to the industry’s fall has made him feel better, not worse, about the future of newspapers. And at a time when journalism schools, including the UW’s, are retooling their programs to take the emphasis off of newspaper-specific writing, he remains one of the school’s most supportive alums.

Rosenthal admits to “walking a tightrope” when he’s writing a column that covers the media business — which includes the company that provides his paycheck. He’s had the cow art that decorates his office since his college days.

Although he says that the format of newspapers needed to change, his faith in their future is based in their history.

“They’re still referred to as papers, despite their increasingly digital orientation, in the same way people might say they dial phones. But on paper, pixel, video stream, or whatever platform they play, these are organizations that over the decades have survived all manner of challenges from within and without. … Those who would write off newspapers as history may wish to consider the adaptability and wherewithal it’s taken for them to get this far,” he wrote in his column about the Tribune Company’s split last August.

Through multiple platforms, newspaper content today enjoys larger audiences than ever, but industry leaders must figure out how to generate the revenue needed to produce it.

•

When Rosenthal first took an interest in journalism, newspapers were still the obvious place to begin. Born on the south side of Chicago, he and his family moved to the North Shore suburb of Lake Bluff where, as a senior in high school, he decided that working as a barback and prep cook at a local pizza pub wasn’t exactly positioning him for the future.

After calling around to various local media outlets, he walked into the News Sun office in suburban Waukegan, where the sports editor agreed to let him cover local high school sports. That experience — and mentoring — gave him the confidence to visit the Capital Times offices a year later, where the sports editor at the time, Rob Zaleski, tried to nicely explain that he didn’t have any stories for the college kid to write.

“He would come around at least once a week after that. I kept telling him, ‘Sorry, nice to see you, but I don’t have anything for you,’ ” Zaleski recalls. “He was a gentleman, and yet, he was persistent. You couldn’t help but be impressed.”

When one of Zaleski’s regular stringers got sick, Rosenthal got his break. He turned in a story about an Oregon High School football game that was so well reported and cleanly written that Zaleski thought a veteran sports writer had taken the assignment. From that point on, Zaleski regularly called on him for other stories, and Rosenthal, nicknamed Rosie, became a well-liked and ever-present personality at the office, even though he was only officially paid to work part time, Zaleski says.

Rosenthal also impressed professors at the UW, where the journalism program was both popular and prestigious. In the early 1980s, the school enrolled five hundred students who chose from one of five tracks: print, broadcast, public relations, advertising, and research. James Baughman, a longtime journalism professor who taught Rosenthal in a newswriting class, remembers being amused by the fearlessness and gumption the young reporter demonstrated.

In one case, Baughman created a class exercise using details from actual news events in Maine. When Rosenthal couldn’t surmise the facts he needed to tell a complete story, he simply picked up the phone and called city workers in Maine to gather them himself, Baughman recalls.

“What I remember about Phil was that he didn’t need to be in the class — he was that good,” says Baughman.

Rosenthal also impressed editors and professors with his ability to write objectively, even critically, about subjects — such as UW athletics — to which other reporters were more inclined to give allowances.

That early skill came in handy decades later.

“Everyone knew that Phil was destined to become a big-timer,” says Zaleski. “When he was hired by the LA Daily News, it was hardly a surprise.”

With his journalism degree in hand, Rosenthal moved to Los Angeles in 1985, joined the paper to cover college sports and the Rams, and wrote a TV sports column. When an opening as the paper’s TV critic became available in 1989, he landed the position, which evolved into a more general four-days-a-week, pop-culture feature column a few years later. The job lent itself to celebrity encounters and enterprising reporting experiences. He traveled to Washington, D.C., to shadow Sonny Bono in his early days as a freshman U.S. representative. He flew to a remote South Pacific isle to observe contestants roughing it on Survivor. For another assignment, he went shopping with international supermodel Vendela Kirsebom, and she helped him pick out a pair of red-and-white swim trunks — after he’d modeled several pairs for her and a photographer.

And after Jay Leno remarked for the umpteenth time that he regretted never publicly thanking Johnny Carson for handing off the Tonight Show, Rosenthal wrote a column suggesting the perfect occasion to do so would be on Carson’s seventieth birthday. Leno called Rosenthal to argue otherwise, but ultimately, that’s exactly what Leno did.

“It was a great job, a wonderful job,” Rosenthal says.

By 1996, though, the LA Daily News restructured itself to focus more predominantly on the San Fernando Valley and surrounding communities. Rosenthal figured it might be a good time to seek new opportunities. When an old friend offered him a position in the sports department of the

Chicago Sun-Times, Rosenthal happily returned to the Midwest. He wrote a sports column for the paper until 1998, covering the Olympics, Michael Jordan’s last three championships with the Chicago Bulls, and other notable stories. In July 1998, he became the paper’s TV critic, a position that appealed to him because of its seemingly limitless possibilities.

“I viewed it as an opportunity to write about everything,” he says. “Being a TV critic was like being a TV viewer — only louder.”

•

In the larger media context, however, things were changing rapidly.

Newspaper publishers, journalism scholars, and other experts had been cautiously monitoring the arrival of the Internet, not quite sure whether the technology would catch on with the public. Even if it did resonate, many assumed it could happily coexist with newspapers, the way TV and radio had previously, says Baughman, who also serves as chair of the advisory board for the university’s Center for the History of Print and Digital Culture.

But by the early 2000s, Baughman says, as the diffusion of laptop computers and mobile devices, and the spread of WiFi, only made the Internet more appealing, scholars began to realize that the newspaper industry was being threatened by something entirely different.

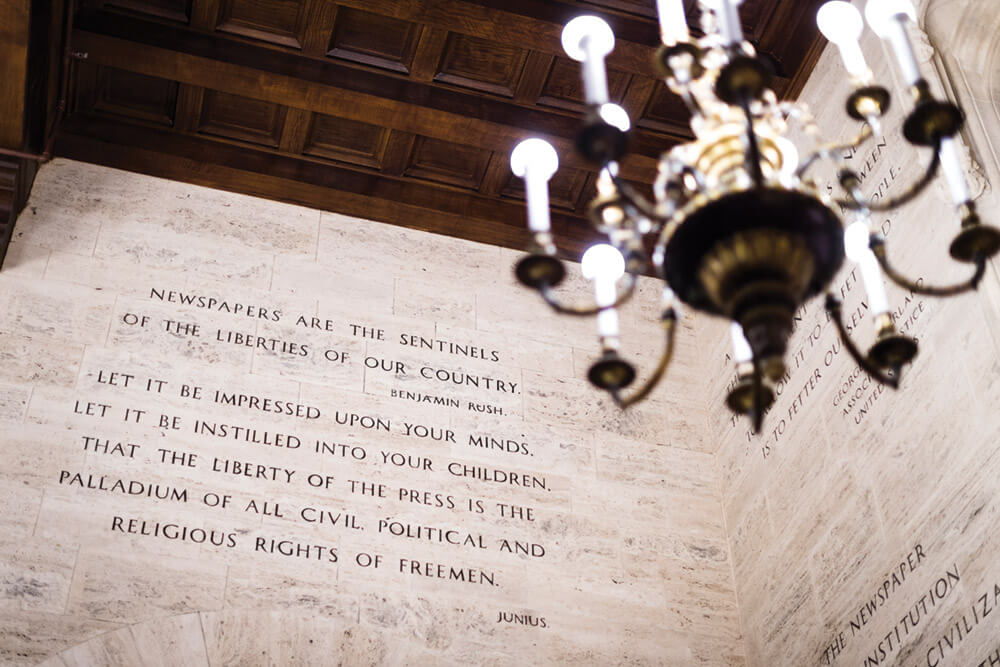

Both chandeliers and words of inspiration grace the lobby of the Tribune building in downtown Chicago.

In the first of several missteps in dealing with the crisis, newspaper companies merged and consolidated debt under the assumption that there would be continued double-digit profits. Then came the decline in revenue. Internet sites such as Craigslist stole away once-unwavering profits from classified ads. The 2009 recession led to a dramatic drop in newspaper advertising and an unfavorable standing to investors on Wall Street, Baughman says.

By the time Rosenthal was recruited to write a media column for the business section of the Tribune in 2005, the newspaper industry was deep in crisis. “Who knows where we’re headed, but we’re headed there fast. The current is strong,” he wrote in his inaugural column in April of that year.

Since then, Rosenthal has chronicled two separate sales of the Chicago Tribune that have brought in colorful casts of new leadership, a Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and the company’s division into two entities — not to mention the struggles of other major newspaper companies across the nation. Those who know him say he’s the right person for the delicate job.

“He just has an amazing integrity. He’s always going to do the right thing,” says Bill Adee, executive vice president of digital development and operations for the Chicago Tribune who has worked with Rosenthal at three other papers. “In those cases of covering yourself and covering your industry, you’re faced with a lot of choices. In those places, Phil’s always made good ones.”

•

Recognizing the evolution of the industry, directors at the UW’s journalism school revamped its curriculum in 2000 to put less emphasis on writing for specific forms of media and increase training for reporting in general.

Today, the school’s nearly six hundred students must complete a rigorous, six-credit course that introduces them to a “platform agnostic” set of newswriting skills that are applicable to careers in both a multimedia reporting track and PR and advertising, Baughman says. Despite the struggles within the newspaper industry, the school’s incoming spring class was expected to be at or near a historic high. For last fall semester, two hundred and ninety applicants had vied for one hundred and twenty spots, and the school’s total enrollment was nearly double that from a decade ago, according to academic adviser Robert Schwoch.

•

Rosenthal regularly returns to Madison for guest lectures, has served on the journalism school’s board of visitors, and co-operates a Facebook page, Friends of Badger Journalism, with another J-school alum, Ben Deutsch ’85, who is now vice president for corporate communications at the Coca-Cola Company.

Regardless of the dramatic changes he’s seen, Rosenthal remains optimistic about the future of journalism — and newspapers specifically. He believes that the newspaper industry will make it through by forcing itself to offer unique, expert, and informative perspectives that readers can’t find elsewhere. He asks himself whether he’s doing so with every column he writes, and he’s embraced social media opportunities to interact with people he might not reach otherwise.

At the end of the day, he’s not so worried about the aging artifact on his desk. True, it has been around for a long time. But, he argues, perhaps that in itself is a reason to believe in its future.

“One of the reasons I’m hopeful about the newspaper business,” he says, “is that we produce something every day. We create. We solve problems every day. We are always adjusting. Most industries don’t have that.”

Vikki Ortiz Healy ’97 is a metro reporter and health and family columnist for the Chicago Tribune.

Published in the Spring 2015 issue

Comments

Fred Fleming March 5, 2015

Grizzly crime scenes? Again, the polar bears go without being arrested…

Stanley Woodward March 5, 2015

Impressed that Mr. Rosenthal covered grizzly crimes in the San Fernando Valley and Chicagoland. Had no idea bears still roamed the area. Were the crimes also grisly?

Ed Chambers March 6, 2015

Actually, he reported on grisly crime scenes.