When Black History Is Your Own

Professor Thulani Davis provides a personal perspective on studying the past.

Like an offshore breeze, Thulani Davis unsettles the air. Conversations with the assistant professor of Afro-American studies swirl through three centuries of black American history, including the lives of Davis’s own ancestors.

Like an offshore breeze, Thulani Davis unsettles the air. Conversations with the assistant professor of Afro-American studies swirl through three centuries of black American history, including the lives of Davis’s own ancestors.

Davis, a soft-spoken native of coastal Virginia who joined the UW faculty in 2014, admits that teaching about the legacies of slavery can be painful. “My aunt was one of those picketers they sicced dogs on,” she says. This visceral connection to the past informs her life and work — and brings the Reconstruction era of American history alive for her students. Davis landed here last fall after an illustrious, forty-year career as a writer, playwright, librettist, poet, and screenwriter. Her latest act: helping convince President Obama to create a national monument to slavery in 2011.

We caught up with Davis over a cup of tea and a conversation that lasted two hours — like any true Southerner, she loves to talk.

After working for The Village Voice, penning plays, poems, and a novel (titled 1959), and even winning a Grammy for writing the liner notes for Aretha Franklin’s The Atlantic Recordings, how do you like teaching at UW–Madison?

I find it fun. It’s not my first teaching job — I taught writing at Barnard College for seven years, and at a few other places as well. But it is my first time teaching about Reconstruction, which was my dissertation topic at New York University. Students don’t know much about that period, I’m discovering. They don’t really learn about it in high school.

How do you draw students in?

I take them through an interesting exercise. I ask them to imagine they are enslaved on a plantation one day, then freed the next. What do free people need? They all seem clear that they’d need education, rights — all the things black people were denied. But I make them get very literal. Anyone who is displaced needs water. Needs food. Needs shelter. Then they need a safe place to meet, for support but also to plan and organize themselves to move forward.

These are things I know, because my great-grandfather was faced with this situation.

What is your great-grandfather’s story?

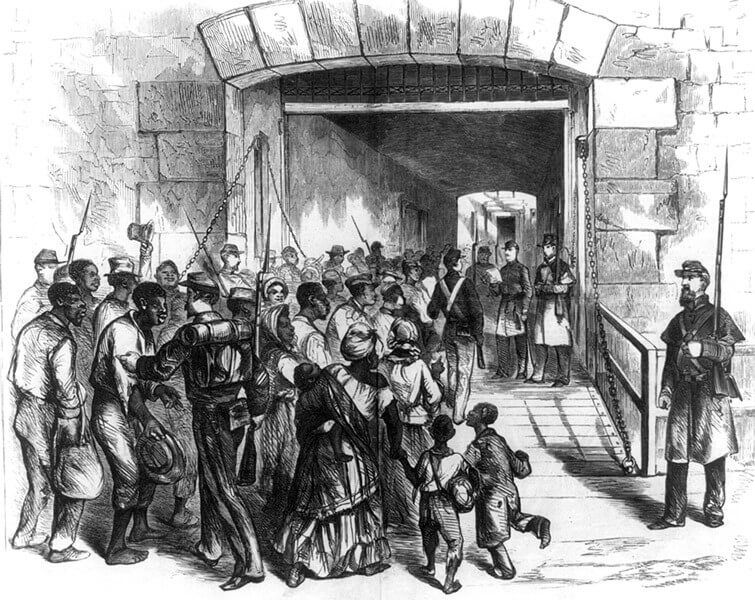

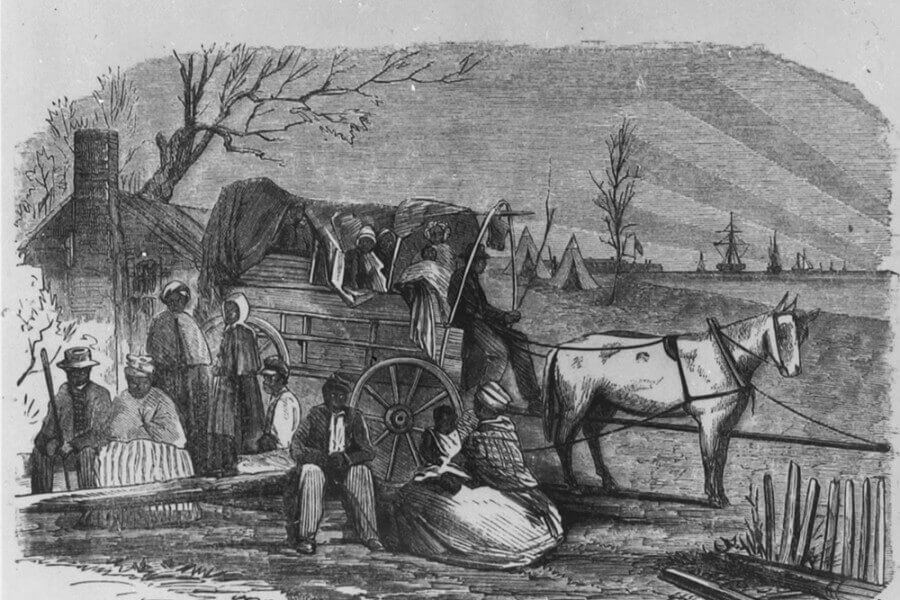

In 1862, my great-grandfather, William Roscoe Davis, piled his family in a farm wagon and sneaked through the countryside of Tidewater Virginia to Fort Monroe, which had just fallen to the Union army. He had gotten word that post commander Major General Benjamin Butler was declaring all slaves in the vicinity “contraband of war.” For my great-grandfather, who was fifty years old and a slave all his life, that was the first step to freedom. And he and his family eventually became some of the founders of the African-American community in Hampton, Virginia, where I grew up.

The amazing thing that I found out much later was that Fort Monroe was both the beginning and the end of slavery in America. The first twenty documented Africans, brought from Angola to Jamestown in 1619, were actually first traded to Virginians at Fort Monroe. So here my great-grandfather was — along with ten thousand other slaves — freeing himself by coming to the exact same place, two hundred years later.

Did that family story spark your interest in studying this historical period?

You know, I didn’t think anything of that story when I was young — lots of people in my town had a similar story. Most people had a grandfather who was a child of the local planter — it was boringly common. And older people did not necessarily want to talk about slavery very much. But the real legacy was community. We lived in a community that really knew how to organize to make change and get things done. In my research, I show the ways that was sustained through the decades.

Your novel, 1959, portrays that very close-knit community you grew up in, as it faced down Jim Crow laws. Why was, and is, community so important?

Pretty much all [that] black people felt they had, when they came out of the Civil War, was each other. They didn’t have houses, they didn’t have schools. The Freedman’s Bureau was forming, but it had setbacks and some serious problems. Black people formed these “benevolent societies” to help one another. But white Southerners were very worried about black people having meetings.

I teach about the Ku Klux Klan terrorism in the 1870s, when the Klan burned organizers’ homes. There was a massacre in Georgia when black people tried to hold a meeting in the town square — forty-nine people were wounded, and nine died. The question I ask my students is, “Would you risk your life for a meeting?” And they get that instantly. Hopefully no one will ask them to take a chance like that.

Is it hard to teach about this painful time?

Some days it is. Not every day. You know, Southerners have such a sense of humor. My aunt, who is now ninety-four, celebrated the end of segregation by going to a hairdresser — for white people!

So how does your previous life as a public intellectual inform your new life as a UW-Madison professor?

What black culture — growing up in it, writing about it — taught me was never to assume that we live in a completely open, transparent world. My schoolteachers taught me how to read the newspaper with skepticism. We were told to imagine what is missing, what is not reported. I’m amazed sometimes at the questions people do not ask. Journalism was a great business to be in. I miss it to this day. I want my students to be skeptical. I want them to look for connections.

In 2011, you had a hand in something quite … monumental. What happened?

I spoke at a celebration commemorating Hampton’s four-hundredth anniversary, and the Contraband Society asked me to join forces with them to convince President Obama to designate Fort Monroe a national monument. I wrote a letter describing my great-grandfather’s journey, and I gathered lots of signatures from well-known people. And in 2011, President Obama declared [it] the first national monument to slavery. To the extent that my letter helped President Obama make up his mind, I think it was a good illustration of the power of storytelling.

Mary Ellen Gabriel is a senior university relations specialist with the College of Letters & Science. Talking with professors such as Thulani Davis is the best part of her job.

Published in the Summer 2015 issue

Comments

joe shaa February 4, 2026

A really compelling piece. I love how Thulani Davis connects big historical moments to everyday human needs—food, shelter, community—making Reconstruction feel real and urgent, not distant. Her great-grandfather’s story at Fort Monroe powerfully shows how personal history and storytelling can shape how we understand the past and even influence the present.

Joe Shaa

Founder : https://8171webportal.me