Whatever Happened to the Badger Yearbook?

A curious student traces the end of a campus tradition.

It was 2019, and I was a freshman visiting the office of the Daily Cardinal for the first time. Disoriented by the mazelike layout on Vilas Hall’s second floor, I turned to the signage for help and noticed a locked door with a simple nameplate: Badger.

Three years later, I had still never seen the door to that office open.

After a little bit of investigating, I understood: the Badger, as the UW–Madison yearbook was officially known, was last published for the academic year 2013–14. My mission now was to find out what the yearbook meant to the campus community and what drove it to its death.

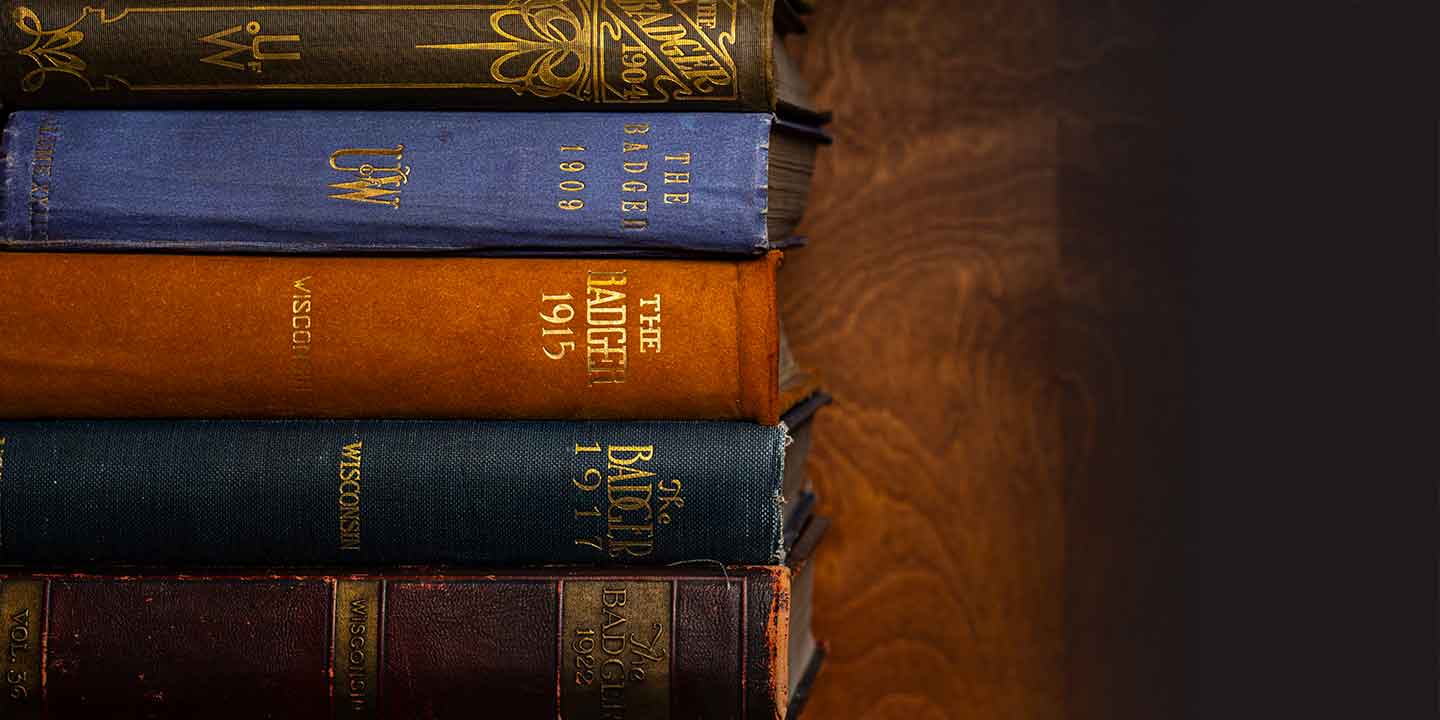

The Badger was once a valued part of the student experience. The yearbook made its debut in 1885 under the name Trochos, from the Greek word for hoop or wheel. After a two-year break, it appeared again in 1888 under the name Badger and was published from 1888 to 2014, with one hiatus in 2004 due to “financial, staff, and content problems.”

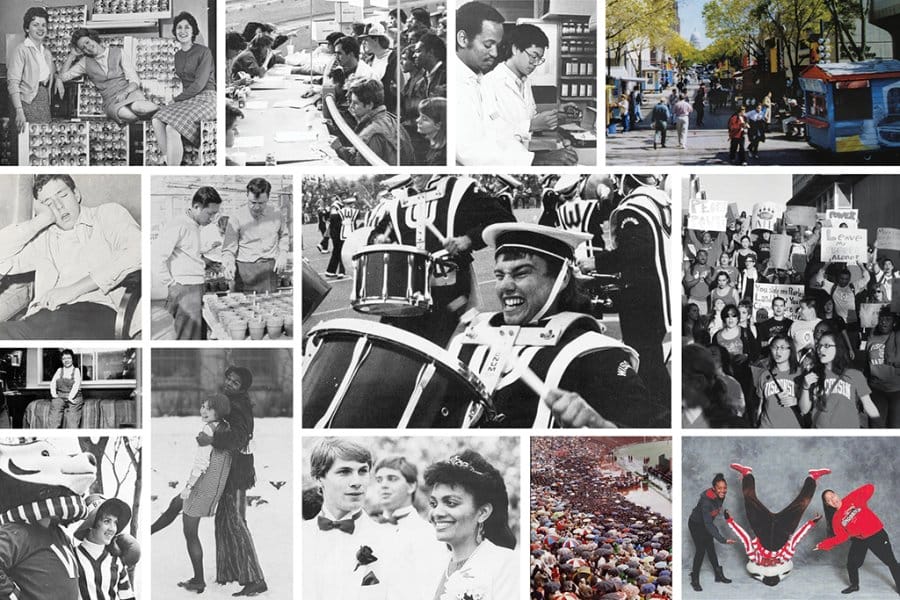

The publication often reflected the mood on campus. Early issues featured line drawings and spartan, black-and-white photographs. Editions from the 1920s boasted elaborate, colorful art deco illustrations, including whimsical but elegant depictions of football fans attending games in suitcoats, dress hats, and heels. Midcentury books showcased the expected bobby socks, saddle shoes, and pleated trousers, and full pages were devoted to glamour shots of winners of the Badger Beauties contest for women students.

During the Vietnam War era, the yearbooks took a turn toward the somber. From 1970 to 1974, the Badger was laden with photos, and text was sparse. The books resembled photo journals that reflected on rather than celebrated the years gone by. But the traditional format soon returned, and from 1985 to 1987, the publication was profitable and won awards. According to Steven Lehr ’87, the yearbook’s managing editor in 1986, campus was enthusiastic about the yearbook.

“People wanted to participate because it was a record of a moment in the university’s history, and they could show they were a part of it,” Lehr says. “Some of it was the tradition: getting a senior photo taken to reflect your achievement and being photographed as part of a group to which you belonged.”

The staffers were proud to be a part of the yearbook, too.

“It was also a paid job that we all took seriously,” Lehr says. “We hoped we were contributing to something bigger than ourselves and that we would have something that said, ‘This is how it was, and this was who we were at that time.’ ”

Hugh Scallon ’91, sports editor for the Badger in 1989, appreciated that the yearbook was a mainstay in the student journalism community. It united the two student newspapers. He worked for the Badger Herald but enlisted Daily Cardinal staffers for the yearbook sports section.

“It allowed me to meet more people and opened up my access to that group,” Scallon says.

At the time, the yearbook was an institution all its own. “There was never a sense that this was a dire enterprise. In fact, it was very vibrant,” Scallon says. In the 1990s, things got a little more challenging. The yearbook made the switch to in-house publishing in 1993, with no staffers returning from 1992.

“The 1993 book had many difficulties but sold well for the time — more than 1,000 books, I think,” says Anthony Sansone ’94, managing editor in 1993 and editor in chief in 1994.

But when Eliana Meyer ’14, the 2013–14 editor in chief, assumed her position, the yearbook did not have the same allure it had in the 1980s. She made up for this by using different approaches to attract students.

“We would do these outreach events and try to get people excited and involved,” Meyer says. “Students would come for the free pizza, and they would stay and maybe take our contact info, maybe come back for a meeting or two.”

Unfortunately, these tactics proved nothing more than a stopgap.

“We had this fluctuating level of membership, where for a couple months it would be really high, and then people would drop off, and we’d have to start all over again,” she says.

This put a strain on the few dedicated regular staffers. Meyer hoped for 20 to 25 but worked with fewer than 10. This ultimately led to students receiving the 2014 yearbook in 2015.

The drop in student enthusiasm, combined with a lack of continuity, meant the yearbook had reached the end of the road. Meyer was trained in 2013 by her predecessor, Gregory Lehner ’13, and she trained two incoming editors in chief who were supposed to take over for the 2015 edition of the Badger, but both fell through.

“One of them got sick,” Meyer says. “And then the other one just got involved with other things and flaked on the commitment.”

Without these key staff, the yearbook died a sudden death. The Badger may have immortalized memories for nearly 130 years, but it proved mortal. Lehr was particularly disappointed.

“With the rise of social media, everyone can create from their perspective, versus an objective, universal one. Things are far more fragmented and fractured,” he says. “Without a yearbook, we’ve lost a valuable, historic point of reference and a great professional training ground for tomorrow’s talented publishers, editors, and photographers.”

Michael Wagner, a professor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication, says there was little faculty involvement in the yearbook when he joined in 2012. “It’s always hard to know which traditions should die and which should go on,” he says. “I’m a little sad that we don’t have that continuous historical record in the same place, in the same format. That feels like a loss.”

As the last editor in chief of the yearbook, Meyer felt a certain amount of guilt.

“It’s not easy when your name is attached to something that is considered the last,” she says.

But as the years have passed, she has come to terms with the fact that the decline of print media was not under her control. “I have come to forgive myself,” she says. “Realizing that I don’t have to blame myself for it is freeing.” •

Anupras Mohapatra ’23 served as an opinion editor at the Daily Cardinal.

Published in the Winter 2023 issue

Comments

Marcia Topel January 12, 2024

I began working on the Badger staff as a freshman, and continued until I graduated in 1962 as the Associate Editor. At that time the yearbook was still a major part of campus culture. I have so many memories of room 310 Memorial Union, and the talented staffers who spent countless hours there producing a beautiful product.

Ben Z. Pilch, class of 1965. January 12, 2024

I still have my Badger Yearbooks and treasure them. They evoke memories of my years at UW Madison; my friends, classmates, activities and organizations in which I participated, my class photos, etc. These are meaningful to me and reflect my development, education, and personal development during these formative years.

Steven Craw January 12, 2024

Hadn’t heard that the Badger “died” in 2014. Sorry to see it go, but I can understand why it couldn’t survive in these times. I still have my 1966-1970 Badgers to help me remember my friends and times at UW Madison…4 1/2 very good years. The 1970 Badger was the first of the non-traditional Badgers and unfortunately they messed up the coordination of the senior pictures/names (including mine) so the proofing (a difficult task for sure) apparently wasn’t up to Badger standards that year.