Weight of the Words

When Henning Garvin realized that the Ho-Chunk language – heavy with his tribe’s history and culture – was in danger of extinction, he stepped in to help.

Chloris Lowe, Sr., a Ho-Chunk elder, speaks to children using his native language at a day care facility in Tomah, Wisconsin. Pairing the tribe’s oldest and youngest generations, tribal leaders hope, will preserve the Ho-Chunk language.

Smoke rose from the lips of patrons and the tips of their cigarettes, clouding the high ceiling of the Ho-Chunk tribe’s Majestic Pines Casino in Black River Falls, Wisconsin.

It was spring 2000, and then-twenty-four-year-old dealer Henning Garvin ’03, wearing a bow tie and tuxedo shirt, fanned out cards on a green felt table and wondered how many more nights he — a UW-Madison dropout with no degree and no prospects besides tips from gamblers — could keep dealing blackjack until 2 a.m.

Then, the bad luck that had taken him there changed, reversed by an off-color joke.

A man — a grandfather to Garvin in the Ho-Chunk way of reckoning — walked past, clasping two buckets of quarters he’d won. Making an earthy pun in the tribe’s traditional language, he compared his jackpot to a mother’s milk and breasts.

Back then, Garvin didn’t know Ho-Chunk well, so he can’t recall exactly what his relative said. But he understood enough to laugh. Then his boss walked over with a fateful question.

“What did he say?” the older man asked.

Henning Garvin, right, and his father, Cecil Garvin, listen carefully as students repeat the Ho-Chunk phrases they are learning during a new language class at UW-Madison.

“I [didn’t] pretend I spoke Ho-Chunk, but it struck me that this guy is older than me, and he doesn’t know what that means,” Garvin says, recalling how the joke lost its humor when he explained it in English. “I remember thinking, ‘That’s what they mean when they say lost in translation.’ I understand that now.”

Concerned, Garvin called a Ho-Chunk Nation office the next morning to ask about the state of the tribe’s language. The answer was sobering: like so many languages around the nation and the world, Ho-Chunk is endangered. Once spoken by many thousands, the language is now down to some two hundred aging native speakers. The reasons vary widely. In past decades, Ho-Chunk students faced sharp punishments for speaking their language in white-run schools. Today, young tribal members like Garvin are growing up in a society dominated by English and by economic demands that force them to leave their homelands for education and jobs.

Garvin had planned on leaving Ho-Chunk country the same way many of his people do — in uniform. Military service has been part of his family for three generations, and he had planned to earn a degree from UW-Madison and become an army officer. But a minor heart condition had led to an unexpected medical discharge just a month and a half before graduation in spring 1999. His plans upended, Garvin lost his motivation to finish his classes and ended up drifting through nights at the casino.

Now, after an offhand joke, Garvin decided to return to UW-Madison to study the modern discipline of linguistics as a means to learn the ancient language of his people. That language, he saw, was the key to Ho-Chunk culture, carrying everything from its legends to its kinship system. Under the Ho-Chunk way and language, the casino jokester — a distant relative to Garvin in European terms — was a grandfather. The traditional religious ceremonies that Garvin had attended since boyhood were conducted in Ho-Chunk. Even the preferred name of Garvin’s people, who are called Winnebagos by some outsiders, is rooted in their language. Ho-Chunk means “people of the big voice” or “people of the sacred language.”

One prophecy among Ho-Chunk elders holds that when their language is lost, the world itself will end.

UW-Madison linguist Rand Valentine, who became one of Garvin’s professors, sees the loss of languages in terms almost as stark. A specialist in Ojibwe, the language once known as Chippewa, Valentine said the likely death of most of the native languages across Wisconsin and the rest of the nation represents an incalculable loss to the shared history and culture of Indians and non-Indians alike.

“It’s like burning your libraries,” Valentine says of the loss. “It’s like killing your past.”

For Garvin, that past was represented by his grandmother, the woman who had helped raise him while his German immigrant mother worked on her master’s degree in finance and his Ho-Chunk father worked to support the family’s life in their Stevens Point trailer home. Garvin grew up hearing the language from his grandmother, a native Ho-Chunk speaker who lived next door. If the language disappeared, Garvin stood to lose one of the most basic ties to his grandmother and her generation of Ho-Chunks, forfeiting their prayers, songs, and stories along with the very words that formed them.

“I thought about — on my mother’s side — if I don’t learn German from her, I can always go to Germany if I want to,” Garvin recalls. But with Ho-Chunk, he realized, “Wow, if it ends here, it ends here.”

What’s that called? Children at a day care facility in Tomah, Wisconsin, point to objects in a painting as they learn Ho-Chunk words from tribal elder Chloris Lowe, Sr., left. Henning Garvin, right, conceived the idea of pairing his tribe’s generations to preserve the language.

When Garvin initially called the tribe’s language division in 2000, the agency had already been working for seven years to save Ho-Chunk, but hadn’t made enough progress. In time, Garvin would use his studies to try to help, putting him among a younger generation of tribal leaders that is marrying a love of ancient traditions with the latest findings about how to preserve them. In doing so, these leaders are grappling with a paradox of modern Native American life: how can tribes hold on to their past while meeting the challenges of the present?

In Madison, Garvin’s first stop was coffee with Valentine. As the professor talked about how linguistics could help make sense of a language like Ho-Chunk, Garvin grew excited.

“He’s really quiet and soft-spoken, but there’s just this energy, just this incredible energy in his eyes,” Garvin says of the professor who became a mentor to him. “That was really inspiring to me at the time.”

Valentine, now the director of the university’s American Indian Studies Program, called Garvin a natural linguist.

“I’ve always had the dream — I tell Henning this all the time — of him coming back and teaching Ho-Chunk at the university,” Valentine says. “This is Ho-Chunk land, and … we very much want to honor them and recognize their preeminence here by offering the language.”

The son of a Canadian mother and an American father, Valentine has studied the many dialects of Ojibwe in both countries. He’s written a grammar of Odawa, a prominent dialect of Ojibwe that is spoken along the northern shores of Lake Huron. He’s also working with collaborators on dictionaries of both Odawa and Western Ojibwe, a dialect that is spoken in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and northern Ontario.

Valentine stresses that while linguists can document and teach about endangered languages, only tribal members like Garvin have any chance of reviving their use. He likens an academic linguist’s work to that of a photographer who captures an image of a dying patient.

“Taking a photograph is not saving the person, and that’s what we can do to some extent,” he says.

Still, an enduring record of a language can mean everything. In a spare office on the eleventh floor of Van Hise Hall, the sole amenity of which is a sweeping view of Madison’s isthmus and the capitol, linguist Monica Macaulay has stacked 465 compact discs. They hold hundreds of hours of digital recordings of tribal elders speaking in Menominee, a language found nowhere else but Wisconsin. Only about fifteen native speakers remain on the tribe’s reservation northwest of Green Bay.

Using a three-year, $310,000 federal grant, Macaulay and a rotating cast of graduate students are drawing on these recordings and other work with elders to produce three dictionaries in Menominee.

Macaulay is putting the final touches on a three-hundred-word picture dictionary for tribal students and others beginning to learn Menominee. By this summer, she hopes to have a draft of a five-thousand-word dictionary in Menominee and English for intermediate learners. Then comes the work of a lifetime — a comprehensive electronic dictionary of the severely endangered language, complete with digital recordings of the pronunciations of its words.

“Of course, [the electronic dictionary] will probably not be finished until I’m in my nineties — but you know, I’ll just work on it. It’s fun,” Macaulay says. “It’s a linguist’s idea of fun.”

Macaulay once approached languages such as Menominee as the mere subjects of her scholarly studies, which were sometimes of no interest to a tribal audience. Now she also sees in her work an opportunity for service through projects such as the beginner’s dictionary. “The Menominee [people] have really kind of retrained me in a way,” she says. “It’s become more and more apparent to me that — as much as I may love doing my linguistic analysis — [it] doesn’t help them very much and that I do owe them something.”

Sasanehsaeh Pyawasay ’07, one of Macaulay’s former students, is likewise thinking about service as she works on her master’s in education leadership and policy at UW-Madison.

“I really want to give back to my community, whether that be on campus working with American Indian students, or whether that be working with my tribe,” says Pyawasay, a Menominee whose first name means “Little Suzi.”

Henning Garvin explains the role of positionals — whether someone is standing, sitting, or lying down, for example — in the Ho-Chunk language during a new course he is teaching with his father at UW-Madison.

On behalf of the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, Pyawasay has reviewed emerging research that suggests Native American students do as well or better academically in classrooms that integrate their culture and language as they do in classrooms that do not.

That’s good news for Lisa La Ronge x’94, an Ojibwe teacher who attended UW-Madison in the early 1990s. Along with her husband, Keller Paap, and many others, she founded a charter school for native students in Hayward, near the reservation of the Lac Courte Oreilles band of Ojibwe in northwestern Wisconsin. Students at Waadookodaading school, the first of its kind in the state, are taught every subject except English in Ojibwe.

Like Garvin, Paap, and some other young native language learners in the state, La Ronge grew up away from her tribal community. At her school in Eau Claire, she was the only native student, which made her appreciate her frequent trips back to the Lac Courte Oreilles reservation.

“There were times in my life growing up when I realized that something was missing,” La Ronge says. “There was something in me that I knew was home, and I just had this device that was pulling me home.”

While still at UW-Madison, La Ronge listened as Winona LaDuke, the Ojibwe environmental activist and a future Green Party vice-presidential candidate, used a campus speech to urge native students to learn their languages.

“I remember thinking about [Ojibwe] and wondering, ‘Well, how would I learn it?’ ” La Ronge says.

Studying Ojibwe with her grandparents, both native speakers, and at the University of Minnesota as a transfer student, La Ronge plunged deeper into her tribe’s language and lore than many of her peers who had never left the reservation. In time, her work with Paap and tribal teachers and elders led to the charter school. Waadookodaading, which means “the place where we help each other,” opened in 2000, and now has twenty-seven students — and a waiting list — in pre-K through fourth grade.

To help teach students and their parents, the school uses computers and MP3 players, and draws on academic research about language acquisition. Being open to these outside influences can be challenging for some tribal members and elders who remember a time when white schools punished native students for speaking their own language. But to La Ronge, using the tools of modern technology and linguistics is no different from tribal members using electric lights and motorboats as they carry on the ancient practice of spearing walleye, a task once accomplished by torchlight and canoe.

“Why wouldn’t you use [these tools]?” she asks.

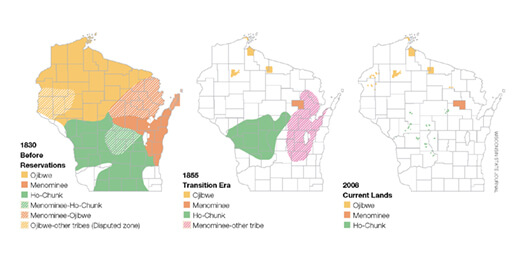

Fading words: The territories of native languages, once blanketing Wisconsin, today have nearly disappeared. Wisconsin State Journal graphic.

For his part, Garvin was also determined to use every means at hand to further the use of Ho-Chunk. He went “berserk,” he says, as he studied the language, speaking whenever he could with his father and grandmother, and devouring the scarce materials available. Once he graduated from UW-Madison with a bachelor’s degree in linguistics in 2003, Garvin began working at the tribe’s language division. Along the way, he met his future wife, Kjetil, also a Ho-Chunk language worker, who graduated from Dartmouth College’s anthropology program.

During those years, the language division’s leadership acknowledged a problem: despite an investment of tribal casino money, the program wasn’t producing enough fluent speakers. When Henning’s uncle, Richard Mann, took over as the division’s manager in 2006, the Garvins suggested some changes. The couple first proposed pairing fluent tribal elders with young adult apprentices who would be dedicated to learning the Ho-Chunk language. They also suggested starting, at the same time, a day care program for infant children where only Ho-Chunk would be spoken by the elders and apprentices.

The couple thought they were just offering advice. Henning Garvin, who had pursued linguistics solely as a way to learn Ho-Chunk, had developed a passion for the field itself and decided to enter graduate school. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, his school of choice, accepted him for fall 2006. But as the start of the academic year approached, Mann called Garvin into his office.

“Cuusge,” Mann said, using the Ho-Chunk word for nephew. “I really need help, and I wonder if you and Kjetil would consider putting off your schooling for a while so we can get things going.”

Garvin’s first reaction, he recalls, was to laugh — given that in a week, he was leaving to find an apartment in Boston. But all that day, he thought about how nephews in his tribe should show respect for their uncles. He thought about the language work to be done in Wisconsin; about his infant son, Haakon; and about his dream that someday the boy would learn to speak Ho-Chunk. By that night, he and Kjetil had decided to stay. With the help of older native speakers such as Kjetil’s now eighty-one-year-old grandfather, Chloris Lowe, Sr., they started the new language programs in summer 2006.

Mann hasn’t forgotten the couple’s decision. “I’d do anything for those kids,” he says. “They gave up a lot just to work here.”

Today three-year-old Haakon chatters in Ho-Chunk with his great-grandfather, along with the other children in the small day care. When it came time for Garvin to report back to tribal leaders that the children were saying their first words in the language, he was unexpectedly moved.

“I’m not a very emotional person, but I felt very emotional,” he says.

Another sign of progress is a team of German linguists who have used a grant from the Volkswagen Foundation to work on documenting Ho-Chunk in a dictionary, grammar, and body of texts. One of the linguists, Iren Hartmann, is now serving as an honorary fellow at UW-Madison, working under a contract with the tribe — with support from Garvin’s father — to write an introductory grammar to the language.

In time, Hartmann and another German researcher want to compile an academic grammar of Ho-Chunk that would delve into features such as its lack of adjectives (it uses verbs to express similar ideas). If documented, Ho-Chunk’s unusual features can serve as data for future linguists studying how both language and the human mind work.

Garvin is once again considering graduate school, with a goal of becoming a professor. In the meantime, he, his father, and Hartmann are teaching a new UW-Madison class this spring — the first Ho-Chunk course on campus designed for learning the language rather than linguistic analysis.

Soon, he hopes, a hallway in Van Hise will echo with the voices of students trying out phrases in the language he loves.

“I think that would be incredible,” he says.

Freelance writer Jason Stein MA’03, who holds a master’s degree in journalism, is also a state capitol reporter for the Wisconsin State Journal.

Published in the Spring 2009 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.