UW–Madison’s Most Famous Frenemy

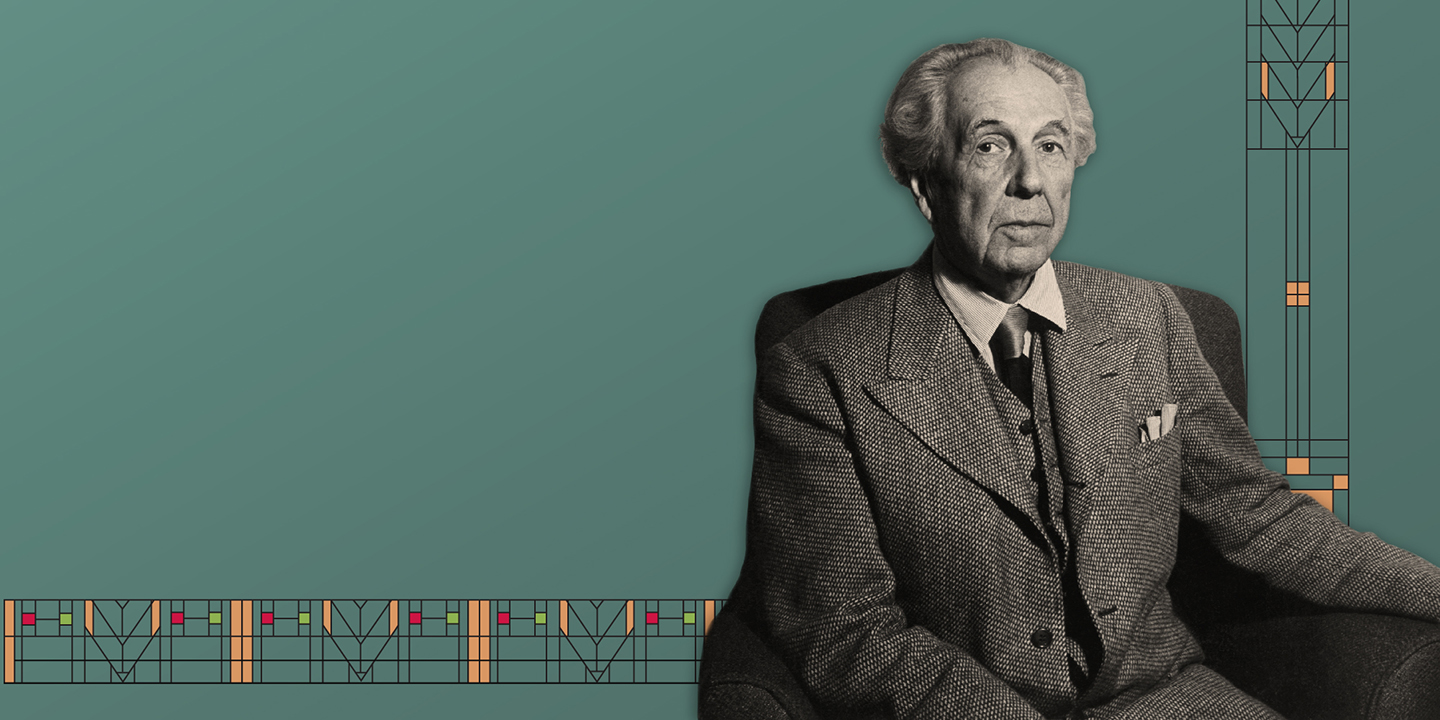

The combative architect Frank Lloyd Wright x1890 had an intense love-hate relationship with his alma mater.

Frank Lloyd Wright x1890 is among UW–Madison’s most famous alumni, and perhaps atop the list considering the architect’s 1,000-plus commissions across the world over seven decades.

Wright was controversial for his scandalous love life, and his work was long scorned before being widely embraced as genius. His prickly personality and contrarian streak did little to boost his reputation among contemporaries. He memorably said that he preferred “honest arrogance” to “hypocritical humility.”

And yet, as this magazine put it in a 1949 profile, “in the end he has usually won his point.” Just as visionaries do, no matter how long it takes.

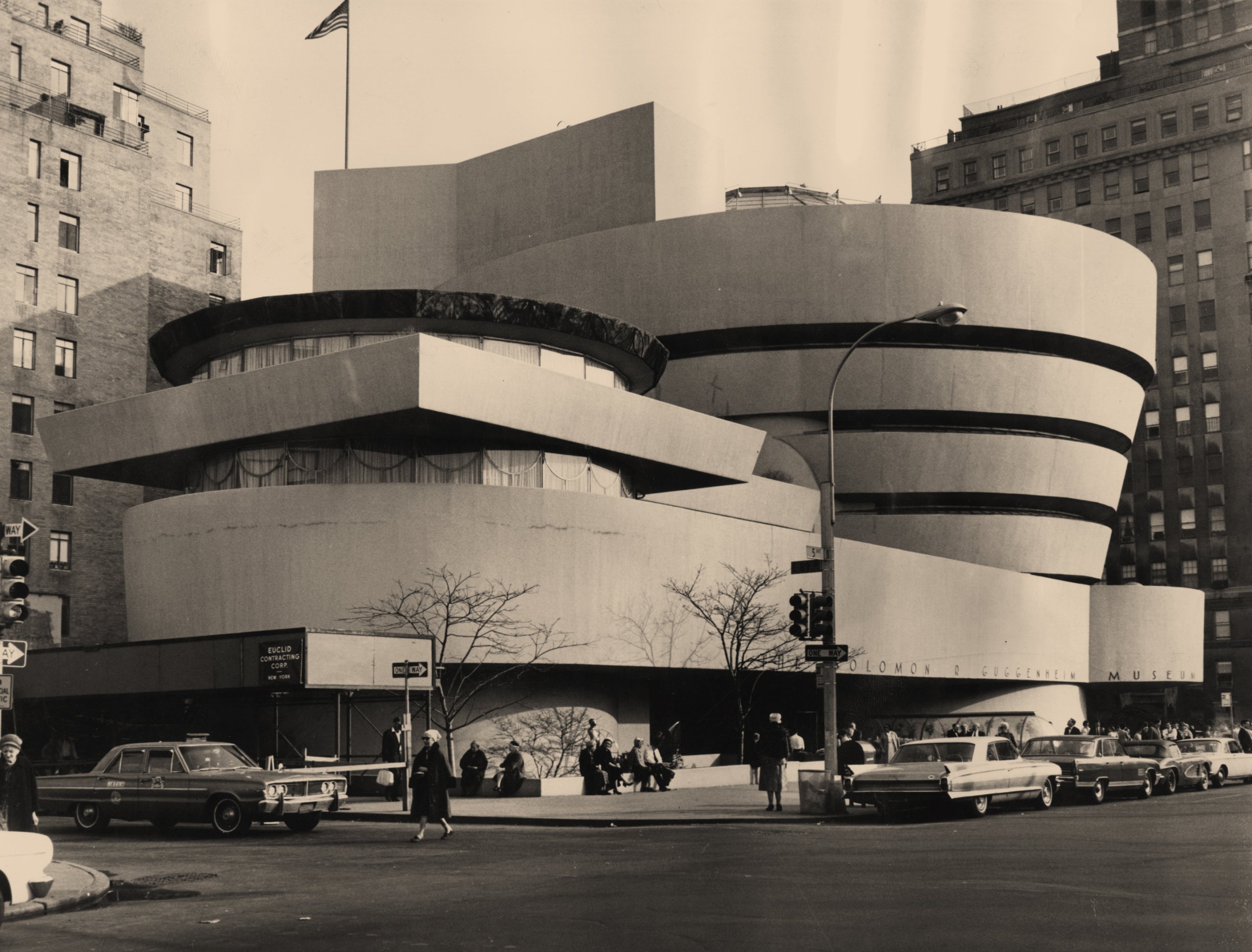

Wright spent his formative years in Madison and lived an hour west in Spring Green for much of his adult life. That proximity forged a lifelong bond between the architect and his home university, one of mutual admiration but shared skepticism. He stayed in regular touch with the UW until his death at 91, in between working on his iconic designs for the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, and the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

So here are seven tales about Frank Lloyd Wright and the UW, showing what happens when a proud radical collides with a buttoned-up institution.

By the time his Guggenheim Museum opened in 1959, the controversial Wright was widely embraced as a genius. Fox Photos/Getty Images

1. Wright falsely claimed that he attended the UW for three and a half years.

Throughout his life, Wright spoke of his university years as a coming-of-age story. In his telling, at the age of 15 — reeling from his parents’ divorce and ready to leave behind family farm work in Spring Green — he enrolled at the UW as a civil engineering student.

“Architecture, at first his mother’s inspiration, then naturally enough his own desire, was the study he wanted,” Wright wrote in an autobiography, referring to himself in third person. “But there was no money to go away to an architectural school.”

Once he arrived at the UW, disappointed by the lack of an architectural curriculum, Wright found “little meaning in the studies.” He claimed that just a few months before he was to receive his degree, he “ran away from school to go to work in some real architect’s office in Chicago.”

But the real story is a bit less inspiring.

After Wright’s death, historians discovered major discrepancies between the former student’s recollections and the university’s official records. Transcripts revealed that Wright enrolled at the UW in January 1886 and stayed for just two terms, that spring and the next fall. He was listed as a “special student,” likely because he didn’t finish high school. Only two courses showed completed grades: “average” in descriptive geometry and drawing.

The UW became aware of the divergent accounts as early as 1955, when it was preparing to award Wright an honorary degree for lifetime achievement.

“Wright’s statement and our record obviously do not jibe,” read an internal memo from mathematics professor Rudolph Langer. He acknowledged that “records are pretty faulty for the years before 1887,” but no evidence has turned up since to suggest an error. And in 2012, UW Archives found a progress report that included a note from Wright’s rhetoric professor that he “failed to appear in class.”

Puzzling biographers even more, Wright also claimed that he was born in 1869. In truth, he was born in 1867, which means that he actually enrolled at the UW around age 18 — just like most of us.

Working on Science Hall is where Wright “really learned most” during his UW student days. UW Archives

2. Wright got his start in architecture as a part-time assistant on Science Hall.

Wright never minced words about his time at the UW, whatever its length.

“The retrospect of university years is mostly dull pain,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Thought of poverty and struggle, pathos of a broken home, unsatisfied longings, humiliations — frustration.”

And if all that weren’t depressing enough: “The inner meaning of nothing came clear.”

To Wright, only mathematics made any sense. And even then, he called his professor, Charles Van Velzer, an “academic little man” who “opened for his pupil the stupendous fact that two plus two equal[s] four.” Ever the idealist, Wright believed the math professor should have approached his teachings as a poet would.

Wright still lived with his mother and sisters while in college, walking two miles to campus each day. Yearbook pages show that he joined the Phi Delta Theta fraternity, the University Choral Club, and the UW Association of Engineers.

With his mother’s help, Wright secured a job with Allan Conover 1874, 1876, a UW professor of civil engineering who operated a private practice. Still a student, Wright was hired as a part-time assistant and draftsman. At the time, Conover was overseeing the construction of the new Science Hall after the original burned down in 1884. The new building was one of the first in the world to be constructed largely of structural steel, and Wright apparently helped to supervise some of the work on the roof trusses.

In his autobiography, Wright shared a story of how the workers, frustrated with the steel clips that were supposed to connect the trusses, deserted the scene and left the materials hanging loosely from the top of the building. He climbed the icy scaffolding in the dead of winter — “nothing between [me] and the ground but that forest of open steel beams” — and retrieved the clips.

It seems that Wright also contributed to the campus’s first boiler house, a central heating plant that later became Radio Hall, as drawings of the trusses matched some of his later work.

“It was with Professor Conover that [I] really learned most,” Wright shared in the rare warm reflection of his time at the UW.

In early 1887, Wright left Madison to start his career in Chicago. He wouldn’t return to the UW campus, at least in a formal capacity, for more than four decades.

3. Later in his career, Wright became a frequent visitor on campus — and a critic of UW architecture.

In the early part of his career, Wright surely felt spurned by the university, which routinely passed him over on commissions. And the university likely feared reputational harm by association, with controversies always swirling around Wright’s romantic and financial affairs.

But by 1930 — his reputation growing first in Europe and Asia and finally in the U.S. — Frank Lloyd Wright’s name was too big to ignore. His achievements started to appear in seemingly every issue of the UW’s alumni magazine. A glowing profile from 1949 began with the line: “The most noteworthy quality about Frank Lloyd Wright is the deep human warmth that issues from him.”

Wright was first invited to speak on campus in October 1930. More than 1,000 people crowded Music Hall for his pair of lectures, titled “The New Architecture” and “Salvation by Imagination.” Walter Agard, a UW classics professor, introduced Wright as “perhaps the greatest architect in the world.”

“To those who love architecture, ‘radical’ should be a beautiful word,” Wright told the crowd. “It is not enough for architecture to take up where others left off.”

He added: “We are a self-conscious nation, and we are afraid to create.”

Wright returned to the UW for similarly high-minded speeches at least five times between 1932 and 1955, typically in the Memorial Union Theater and coinciding with exhibitions of his work. He preached from his gospel of organic architecture, which sought to bring people and buildings into harmony with their natural surroundings.

A proud provocateur, Wright never shied from the chance to criticize his host. In 1932, he mocked the Memorial Union’s architecture as “speaking Italian, extremely bad Italian.” In 1948, he added that “all the buildings that the university has built are heresy,” calling them “dead forms” and “monarchic hangovers unbecoming to a democracy.”

In another lecture, he decried the shoreline buildings for being designed with their backs to the water. Wright believed that the university wasted a “gift of nature” by failing to marry its campus to Lake Mendota.

4. During Wright’s campus visits, he inspired one famous writer and feuded with another.

Wright’s antiestablishment message resonated with at least one UW student and fellow visionary. Lorraine Hansberry x’52, the future playwright and author of A Raisin in the Sun, wrote that one of Wright’s campus lectures left an indelible mark.

“He attacked almost everything … [including] the nature of education saying that we put in so many fine plums and get out so many fine prunes,” she noted. “Everyone laughed — the faculty nervously I guess; but the students cheered.”

Later, with Wright’s critiques still ringing in her ears, Hansberry left the UW to “pursue an education of another kind” — a writing career in New York City.

In 1934, Wright rubbed shoulders with another famous writer on campus. Gertrude Stein, the rare figure who could match Wright’s eccentricity and ego, visited Memorial Union to deliver a guest lecture in which, according to one reporter, she “modestly offered her work as the foundation of modern English literature.”

Afterward, Stein retreated to a party room and recognized an approaching figure in the hallway — the man who, according to the alumni magazine, “had sat in the front row during her lecture [and] slept like the dead.” Stein ordered an attendant to “slam the door quickly and solidly in the astounded face of Frank Lloyd Wright.”

A week later, Wright fired back with a satirical column in the Wisconsin State Journal, mocking Stein’s “simple view of world literature” and insisting on the last word in the bizarre feud.

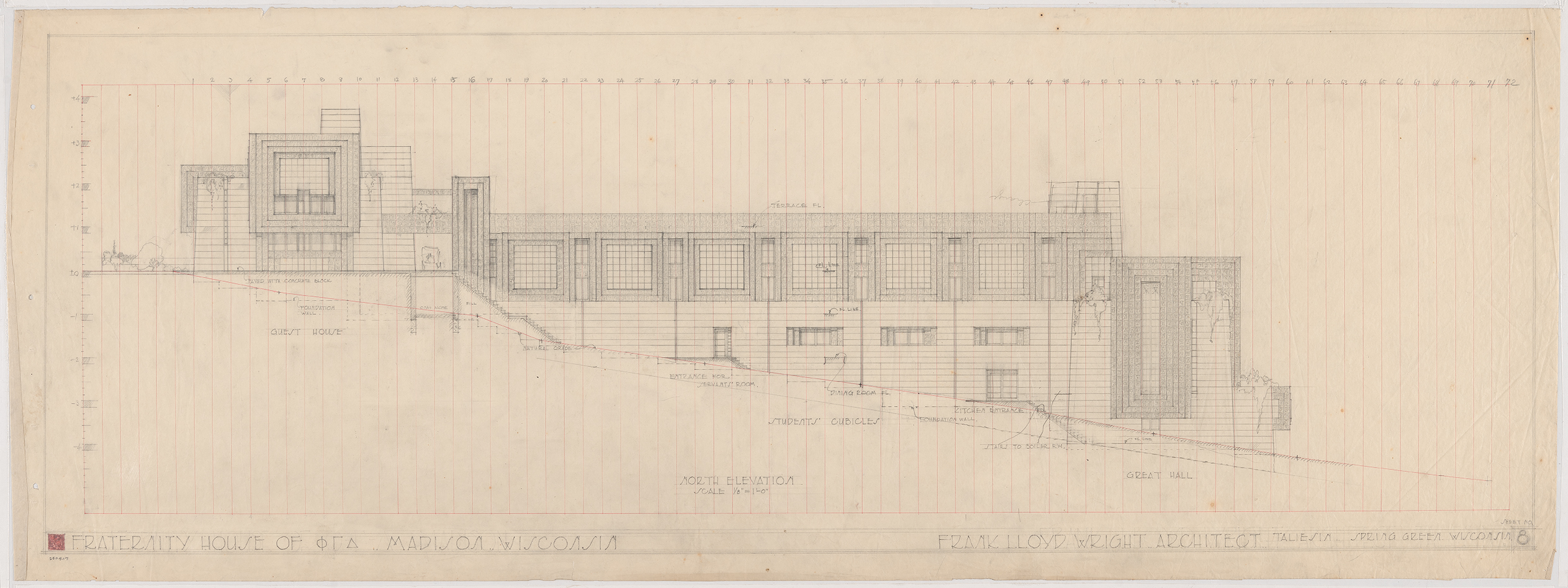

Wright designed a Phi Gamma Delta fraternity house before the alumni lost confidence in him. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library Columbia University, New York)

5. Wright designed two university-related buildings, but neither came to fruition.

Wright was commissioned for more than 30 building designs in Madison, the most of any place in the world. But only two of them — a boathouse for the rowing team and a fraternity house for Phi Gamma Delta — had a direct connection to the university.

In 1905, UW rower Cudworth Beye 1906 asked Wright to design a second boathouse for the crew team along Lake Mendota. The architect responded eagerly: “We are always ready when ‘Alma Mater’ calls — we will design any thing for the [UW] from a chicken house to a cathedral, no matter how busy we may be.”

Just over a month later, Wright sent the sketches and predicted a “somewhat more expensive” project than anticipated. The ground floor, flanked on each side by floating piers, was to house the rowing shells, with a locker room on the level above. Wright’s plans were a confident expression of his budding Prairie style: symmetrical, horizontal, low proportioned, always in unity with its surroundings. It was his first design to incorporate a perfectly flat roof and was among the most abstract of his early work.

There was just one obstacle: UW administrators were never really on board with the plan, and they were far more preoccupied with the football program (which the faculty was trying to suspend over safety concerns). Within months, it became clear that funding for the boathouse would not materialize.

Wright was still clearly proud of the work: it was the only unbuilt design featured in his prominent Wasmuth Portfolio five years later. And in 2007, the UW boathouse design was finally constructed — in Buffalo, New York, under the guidance of a former Wright apprentice.

In 1924, alumni of the UW’s Phi Gamma Delta chapter commissioned Wright to build a new fraternity house at 16 Langdon Street. Wright’s plans separated essential functions into a student wing, great hall, and alumni guest house. The Mayan-inspired exterior followed the narrow, sloping lot, hugging the hillside all the way down, complete with rooftop terraces.

The alumni eventually lost confidence in Wright after a series of personal dramas and rising construction estimates. They discharged the architect and turned the project over to the architectural firm Law, Law, and Potter, which preserved Wright’s three-part floor plan but abandoned much else in its more conventional design.

Even after his death in 1959, Wright’s imprint on campus proved almost cruelly elusive. In May 1965, the State Building Commission approved a resolution to name a proposed student union at the UW in honor of the late architect. But the “Wright Union” was never to be — Union South, sans eponym or even mention of Wright, opened in 1971.

At least you can see Wright’s influence in the new Union South, which was rebuilt in 2011 in the architect’s Prairie style.

6. Wright lobbied the UW to sponsor his Taliesin Fellowship.

In 1928, Wright announced that he was planning to convert the old Hillside School in Spring Green into an “academy of allied arts” with an architectural focus. He reached out to the UW in hopes it would fund and sponsor what would later become the Taliesin Fellowship — his famous apprenticeship program.

Wright was likely inspired by the UW’s Experimental College, a two-year alternative program established by educational reformer Alexander Meiklejohn in 1927. It attracted fellow free spirits, and Wright often sung the experiment’s praises.

Wright negotiated with the university for a year, but administrators ultimately rejected a school located so far off campus. The architect lashed out at UW president Glenn Frank, accusing him of letting Wright’s “domestic situation” (filled with multiple marriages, divorces, mistresses, and custody battles) influence the decision.

Wright opened the Taliesin Fellowship on his own in 1932.

The ordeal soured him even more on traditional education. While the university merely conditioned its students, he argued, the Taliesin Fellowship enlightened them.

Wright explained in the UW’s alumni magazine: “No courses, no credits, no examinations, no teaching. … Our textbook is the one book of creation itself.”

7. Wright earned an honorary doctorate from the UW in 1955 — and tried to receive another degree.

Wright wrote in his 1932 autobiography that he left the UW early because he felt little motivation “just to be one of the countless many who had that certificate.” But that sentiment did not hold true in his later years.

After decades of debate and rejection by the UW’s Committee on Honorary Degrees, Wright was nominated for an Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts during an all-faculty meeting in March 1955.

Wright, soon to turn 87, eagerly accepted the recognition in a letter to UW president E. B. Fred. A week later, he wrote to Fred again, adding a request that he receive his undergraduate degree and turning in what he claimed to be a senior thesis.

“So here is the missing thesis — The Eternal Law — to be back-filed, perhaps, with those of my ancient class?” he wrote.

It contained a dozen typed pages (with penciled edits), many personal views, and zero citations. He argued, with familiar grandiosity, that the only certainty in life is change — “that we are all in a state of becoming, that is to say, of growth, or decay: decay being but another form of growth.”

Fred responded diplomatically: “The honor which we contemplate doing you … so far eclipses the deserts of an ordinary student … that I must protest against your feeling that any ‘repair’ needs be made.” He promised to preserve Wright’s paper in the archives.

Wright handled the rebuff with grace, writing back, “Since it has found a resting place, all is well.”

On June 17, 1955, Wright attended the UW’s commencement ceremony at Camp Randall and walked across the stage to receive his honorary degree “with an ailing back (but also a smile),” according to the alumni magazine.

The citation for Wright’s honorary degree referred to him as a “constructive controversialist.” In conferring the degree, Fred told Wright: “You have labored long and well to release the spirits of men from the shackles of outworn convention.”

It’s clear that the recognition from his alma mater touched the old architect deeply. In his response to the UW’s initial invitation, you can practically hear the sigh of relief in his words.

“No honors are sweeter than home-honors. While the lateness of the hour was becoming a matter for invidious speculation — that is now happily ended.” •

Preston Schmitt ’14 is a senior staff writer for On Wisconsin.

Published in the Winter 2024 issue

Comments

James L Schneider November 25, 2024

Long a fervent admirer of Wright, I found much pleasure in reading this article.

James P. Colias January 6, 2025

With considerable interest I read the fine article (in On Wisconsin, Winter 2024) about connections between Frank Lloyd Wright and the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

For eight years, starting in the late 60’s I was extremely fortunate to be assistant to Gunnar Johansen, the first appointed Artist-in-Residence in Music in America (UW: 1939-1976). From the time that Gunnar and his wife Lorraine moved from Madison to a rural home in Blue Mounds just north of “Blue Mound State Park” in 1946 until the late 1950’s, Johansen was a frequent guest at Taliesin in Spring Green, invited there by Wright to perform solo piano and chamber music for his apprentices. Following FLW’s demise in 1959, there was a brief period where his fame went into a decline. There were no new commissions, and over time the buildings in Spring Green and in Scottsdale, AZ, suffered structural damage.

Co-incidentally, at this time Gunnar Johansen, a man of extraordinary musical artistry and coruscating intelligence (described by his life-long friend Victor Borge as “a walking lexicon of perhaps twenty volumes”) came up with the idea to found an interdisciplinary institute bringing together distinguished experts from many fields to pool their intellectual resources in a synergistic fashion. And so, Gunnar made an appointment to meet with Mrs. Wright to discuss his plan for a “Leonardo Academy” – naming the entity after the greatest interdisciplinarian ever known. This would have been in about 1964; it was some years later that Gunnar related to me his experience that day.

Soon after arriving, he mentioned to Olgivanna Lloyd Wright, “I remember well the many times I was here and enjoyed the stimulation of being in the company of Frank,” to which Mrs. Wright responded, “Mr. Wright, to you!” Eventually, Gunnar got around to his goal and hope which was to try to convince Mrs. Wright to allow the renaming of her late husband’s architectural campus and its purchase for the new function he had in mind. He explained that within the renovated “Leonardo Academy” there would be a separate

independent foundation titled “The Frank Lloyd Wright Institute”. At this point, she declared, “Leonardo da Vinci is not worthy of tying the shoestrings of Frank Lloyd Wright!” Gunnar later said, “Upon hearing that, I came to the conclusion that I was not going to get far with my idea!” He did not … so far as establishing The Leonardo Academy at Taliesin East … nor in another location. But, there were seven symposia that were carried out at various campuses across the USA under the aegis of Johansen’s “Leonardo” plan (which focused on a broad range of topics including cancer research, the hypersonic jet, the future of the university, etc.) drawing participants [such as Buckminster Fuller and Edward Teller] from major institutions in the USA, Europe and Russia.

James P. Colias, Trustee.

The Gunnar and Lorraine Johansen Charitable Trust. January 2025.

Jeff Anderson January 14, 2025

I read the article on Frank Lloyd Wright with great interest. My mother remembers him getting off the train in Madison with his cane and cape flashed around his should with great pomp. I also am intrigued by the graphic designs that decorate the article. Were those FLW designs? Who created them for this article? Well done! On Wisconsin!

UW-Thai-Alumni January 16, 2025

I read from this article that his reputation grew from Southeast Asia but I cannot find any relation anywhere, he was related to Japan, yes, but Southeast Asia? Please elucidate.