The People’s Poet

One of the leading poets of his generation, Martín Espada speaks for those whose voices are rarely heard.

As his undergraduate career in Madison drew to a close, Martín Espada ’81 found himself simultaneously filling out applications for welfare and for law school.

The welfare forms were much more difficult, he says, because “they required me to document where I had been for years and years.” The others basically boiled down to one question: ‘Why do you want to go to law school?’ That answer was easy: to get off welfare.

Now Espada’s business card identifies his profession with one word: poet. He is also a professor of English at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and a member of the Massachusetts bar. Along the way, he has had many jobs. His colorful resume includes dishwasher, bouncer at Madison’s now-closed Club de Wash, door-to-door encyclopedia salesman, bindery worker in a printing plant, and patient advocate for the mentally ill, to name a few.

All of these positions have informed his understanding of the world. He grew up in a rough section of Brooklyn, New York, and in a working class town on Long Island, the son of a Puerto Rican father and a Jewish mother who converted to become a Jehovah’s Witness. As a Latino, Espada has felt the sting of racism and assaults on his dignity. And he inherited from his father, documentary photographer Frank Espada, “a set of political values and a sense of struggle.”

Widely considered a leading poet of his generation, Espada is unabashedly political in his life and letters. The cultural commentator Ilan Stavans calls him “a poet of annunciation and denunciation, a bridge between Whitman and Neruda, a conscientious objector in the war of silence.” Espada joins causes, heralds everyday heroes, chronicles the travails of the downtrodden, and casts his eye on world events. He also brings music to his cadences and revels in fresh and often surprising images and words. His appreciation for literature starts with content. “I am primarily interested in what people have to say, whatever the poet feels must be urgently communicated to the world,” he says during an interview in his home in Amherst.

Espada was in Madison last spring at the invitation of Steve Stern, the university’s vice provost for faculty and staff who is also a professor of Latin American history. Espada gave a reading attended by two hundred people and spoke with students about the influential Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, to whom he is often compared. Stern calls Espada “one of our most distinguished alums,” not only because of the prizes he has won and the fact that top publishers seek him out, but because of the Latin American tradition of melding politics and literature that he embraces with alacrity and profundity.

Espada’s Puerto Rican heritage is an important part of his identity. Yet his themes, often prompted by vignettes from his life, range widely. He has written about tending animals in the UW primate lab; the nightlife in San Juan seen through a historical and political lens; the cruelty of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship in Chile; the plight of evicted tenants; and the felling of the World Trade Center (see “Alabanza,” below).

Stern frames Espada’s importance in terms of the impact Latino authors have had on world literature over the last half century. “Latin America has historically been a region in which writers have not assumed a disconnect between a sense of political obligation to society and a sense of artistic drive and ethos,” he says. “We’re most familiar with that in the realm of novels and movies because of the presence of immigrant and racial themes.” Espada is widening that lens to include his art form, Stern says, adding, “We have failed perhaps to notice how powerfully this literary tradition has inflected poetry.”

Espada crosses cultural and artistic boundaries in ways that bring that ethos home to North Americans. Though his social conscience is obvious, he can’t be pigeonholed as a political or a Latino poet, because his devotion to his art defies such simple categorization. “I’m alien in two lands and illiterate in two languages,” he quips, referring to the fact that he did not master Spanish until he was an adult.

It was while working at a string of low-status jobs after high school that Espada was first inspired to begin writing poetry. He had noticed that he was essentially invisible to the bosses and customers he served. They would do and say things in his presence that were often astonishing for their insensitivity. Recalling his job pumping gas in Maryland, Espada still grimaces. “I can’t tell you the number of times someone would light up a cigarette standing next to me — I could have been blown sky high.”

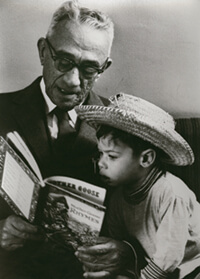

Espada’s father, the documentary photographer Frank Espada, made many portraits of his children over the years. This one depicts Martín as he was about to leave for the University of Wisconsin. Photo: Frank Espada

In response, he took notes, becoming in his mind a “poet spy” on the doings of people who had an internalized sense of privilege. “I don’t think it’s a coincidence that we talk about the ‘invisible man’ as a trope in American literature,” says Espada with a nod to Ralph Ellison’s 1952 book of that title. “When you are a laborer, when you work with your hands, you are only seen for what your hands can do … and that can have its benefits if it so happens that you are writing things down.”

He came to Wisconsin, a state he had barely heard of and couldn’t locate on a map, on the strength of a passing comment by a high school English teacher, who said that it had a good university where he might have a realistic chance of being admitted in spite of lackluster grades during a false start at the University of Maryland. “I was one of those twenty-year-old kids who do what twenty-year-old kids do — they make momentous life decisions on impulse based on very little information,” he says. “I had no idea how cold it was — when I showed up, I didn’t have an overcoat; I didn’t even have boots.”

After arriving as a sophomore in 1977, somewhat to his surprise, Espada thrived academically, but he was forced to drop out after one semester due to lack of money. He went back to menial jobs for a year while establishing residency so he could pay in-state tuition. “I was like a rubber ball, bouncing in and out” of school, he says.

The university and the city shaped him in many important ways. At one point, he moved into an apartment in the building that housed WORT-FM radio, and soon he was spending late nights in his bathrobe spinning discs. “I did a lot of that — I was the mystery midnight programmer,” he says.

At the radio station, Espada developed a close relationship with fellow DJ and poet Jim Stephens, who was active in poetry circles. “Jim, to his eternal credit, was wildly enthusiastic about my work, and this was not a guy who was wildly enthusiastic about things as a rule. He was very laid back, as befits a jazz programmer,” Espada says. He gave his first reading of original work at Club de Wash. Through contacts Stephens gave him, Espada published the first of his seventeen books, The Immigrant Iceboy’s Bolero, in 1982 with Madison’s Ghost Pony Press. It is a collection of observations from his youth in New York illustrated with his father’s photographs.

Espada delved deeply into the history of U.S. domination of Latin America, choosing courses based on his passions. He decided to major in history when he tallied up his credits one day and saw that it offered the quickest path to graduation. Madison was “all about education,” says Espada. “By some miracle, some of the education actually happened on campus, and the rest happened in the street.”

He calls his time in Wisconsin “five of the most valuable years I’ve ever spent anywhere.” He became active in the Latin American solidarity movement, and he also happened upon Pablo Neruda’s work in a used book store on State Street, an encounter that would grow in meaning as his own poetic voice developed. It was a book with both the Spanish originals and English translations. “I read Neruda the way I still read, which is with one foot in each language,” he says.

Espada discovered his penchant for the law in what he calls “an accidental job” with the Wisconsin Bureau of Mental Health. He had been hired as a clerk soon after the legislature mandated that mental patients were entitled to a grievance procedure. After he began his new job, “the patient rights advocate quit and there was a hiring freeze on, so I became the patient rights advocate by default,” he says. “I had no legal training, I was twenty years old and in my first semester at UW, yet I was doing legal work representing committed mental patients at administrative hearings at hospitals throughout the state of Wisconsin.”

He got a second dose of paralegal experience toward the end of his time in Madison when he went to the Dane County Welfare Rights Alliance to obtain emergency food stamps for himself. He subsequently landed a job with the organization as an advocate for its clients.

But he credits his father and the late Herbert Hill, a former labor director of the NAACP and professor of Afro-American studies at the UW, for his ultimate decision to study law. Hill was a mentor who “saw something in me that other people didn’t see at the time,” Espada recalls. He applied to several law schools, and Northeastern University in Boston awarded him a full scholarship.

Throughout this time and then at law school, Espada never stopped writing poems. “I wrote about everything that was going on around me,” he says, and many of his experiences in Madison became grist for later work.

Espada learned more about social and legal priorities while representing poor people in Chelsea, a city in the Boston area with a large immigrant population. “When you are a tenant lawyer, what you are dealing with by definition is the legal system’s clear preference for property over people,” he says. His legal training sharpened his impulses to speak for those whose voices are rarely heard and refined the role that advocacy plays in his poetry.

His career as a lawyer also, as planned, lifted him out of chronic poverty. But while Espada was practicing tenant law in Boston, budget cuts put his job in jeopardy. Instead of playing hardball office politics to squeeze out a more junior member of the legal staff, he applied for an opening in the English Department at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, and began teaching there in 1993.

He and his wife, Katherine Gilbert-Espada, had a son, Klemente, who is now a high school senior. But several years ago, Gilbert suffered a massive stroke, and she has since been susceptible to debilitating seizures. Though they have insurance through his university position, all the attendant expenses of her illness have pushed Espada to spend more time on the road to give readings. “They pay me to go away,” he smiles ruefully.

The mementos Espada surrounds himself with in his home office include an envelope with the face of the poet Julia de Burgos exquisitely painted on the front. A gift from an inmate at a Connecticut prison where he gave a reading, it became the subject of a poem. There is also a platter honoring Espada as the 2007 winner of the National Hispanic Cultural Center Literary Award.

Espada’s paternal grandfather, Francisco Espada, planted a seed by reading nursery rhymes to the future poet at the family apartment in Brooklyn, New York. Photo: Frank Espada

It is one of many accolades, including the Robert Creeley Award, the Paterson Poetry Prize, the Gustavus Myers Outstanding Book Award, the American Book Award, two NEA Fellowships, and a Guggenheim Fellowship.

In his office there are also countless knickknacks. The short list includes a photo of a downed boxer; a bust of Charles Dickens; a vejigante mask, which is a Puerto Rican mythical figure that fuses elements of African, Spanish, and Caribbean cultures; and a political button for Eugene V. Debs, the Socialist Party candidate who, Espada notes, won a million votes in his run for president of the United States from a jail cell.

Also in what he calls a “little museum that reflects the traveling life,” Espada keeps some of the cremated ashes of his dear friend and mentor Sandy Taylor, a co-founder of Curbstone Press and one of Espada’s early publishers.

Espada has never sought to banish sorrow from the things and people he surrounds himself with. On the contrary, he embraces pain with a spirit guided by the possibilities of his craft to clarify and heal. Of his approach to poetry, he writes:

“[T] he unspoken places in poetry [are] hidden or forgotten places and the people who inhabit them: prisons, psychiatric wards, unemployment lines, migrant labor camps, borderlands, battlefields, lost cities and rivers of the dead … poets continue to speak of such places in terms of history and mythology, memory and redemption, advocacy and art. They make the invisible visible.”

Eric Goldscheider is a freelance writer based in Massachusetts.

Published in the Spring 2010 issue

Comments

Maurice J. Lee June 19, 2011

The pen made me say it

to them

inspired by the movement of stanza

comma comma

say it two

between the parenthesis

i know emphasis

u tolerate my motion

to clear my head

the writting’s on the wall

for those who don’t recall

my message

the ink drips

when the clicks

coughs the tip

i am forever cautious

of the period come to end

so i don’t pretend forever

with a semi colon

o’ and…

i’m speechless