The Food Lover’s Guide to Living in Season

Renowned cookbook author Patricia Wells MA’72 went to France to learn haute cuisine and developed a signature taste steeped in simplicity.

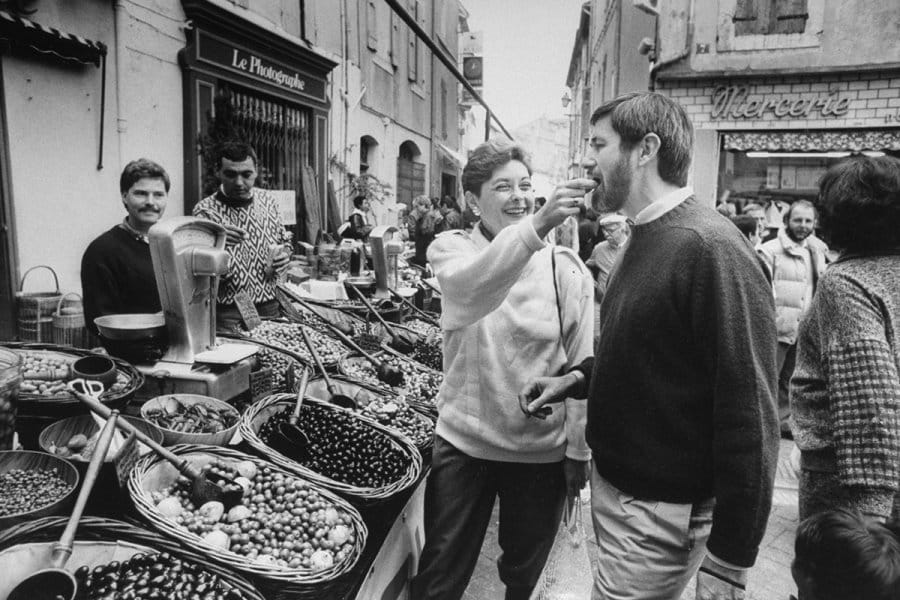

Wells: “If you’re a food lover, you get something out of every meal.” Photo courtesy of Patricia Wells

In the introduction to her James Beard Award–winning cookbook Simply French, Patricia Wells MA’72 describes the cuisine of acclaimed chef and restaurateur Joël Robuchon as cuisine actuelle, an approach to cooking that celebrates and elevates the essential flavors of seasonal ingredients.

“His rule was that our jobs as cooks — as chefs — is not to make a mushroom taste like a carrot,” she says. “Our job is to make a mushroom taste as much like a mushroom as it can.”

Wells credits her time shadowing the late Robuchon, considered one of the greatest chefs in the world, with a profound influence on her own cooking. But her reverence for simplicity and her thoughtful appreciation of seasonality — in food, in places, and in people — can only be described as Wells actuelle.

Over the course of almost 50 years, most of which have been divided between a chic Paris apartment and a charming Provençal farmhouse, Wells has traversed the culinary world with elegance and humility, regarded it with admiration and fascination, and rewarded it with sparkling homages to the life’s work of people who, like her, know what it means to truly love food.

“If you’re a food lover, you get something out of every meal,” Wells says. “Food offers so much pleasure every single day.”

In Wells actuelle, loving food is a timeless art form, and throughout her career, Wells has become an international authority on both fine cuisine and simple pleasures.

Well-Read and Well-Fed

Wells didn’t set out to be a food journalist, but Wells actuelle was in the works long before her first culinary byline was published. Growing up in Milwaukee in the 1950s, Wells (née Kleiber) can’t recall a meal that came from a freezer or a takeout bag.

“I grew up thinking I’d always have great food to eat,” she says. “Everything was homemade, and the cookie jar was always full.”

Wells’s mother, Vera, was a first-generation Italian American. Her maternal grandfather, Felix Ricci, came to the United States from the Abruzzi region of southern Italy in 1915. After landing in New York City, he traveled to Wisconsin to join a growing population of southern-Italian immigrants and established a dairy farm in Cumberland. Wells and her family paid regular visits there throughout her childhood.

Wells was also as well-read as she was well-fed. Her father worked for Gimbels department store and returned from buying trips in New York City with stacks of daily newspapers that his children pored over. “When I was in third grade, I remember we were writing on the blackboard, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ ” Wells says, “And I wrote, journalist.”

She followed the scent of newsprint to the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee for an undergraduate degree in journalism before heading to UW–Madison for a master’s in reporting, specializing in art history. She moved to Washington, DC, where she was hired as a part-time editor at the Washington Post (the very same week as the Watergate break-in) and was given a column on art galleries.

It didn’t take long for Wells to tire of the art beat. In 1976, she moved to New York City to work as a copy editor for the New York Times, where she landed her first gig as a food writer under editor Craig Claiborne. It was also at the Times that she met her husband of nearly 50 years, Walter Wells.

In 1980, the couple moved to Paris for Walter’s new job as managing editor of the International Herald Tribune, an English-language newspaper with readers in 164 countries. Wells joined him as the Herald Tribune’s global restaurant critic. The move, a two-year sojourn that’s lasted 45 years, marked the beginning of Wells’s storied career as one of the world’s foremost voices on French cuisine.

An American in Paris

If Julia Child brought French cuisine to American kitchens, Wells actuelle teaches Americans to think like French chefs.

In addition to penning her restaurant column in the Herald Tribune, Wells became a prolific author. Just four years after moving to Paris, she released The Food Lover’s Guide to Paris, a robust collection of eateries and culinary storefronts that has gone through five editions and turned into an app. Paris was followed quickly by A Food Lover’s Guide to France (1987), Bistro Cooking (1989), Simply French: Patricia Wells Presents the Cuisine of Joël Robuchon (1991), and 14 more cookbooks and memoirs.

From 1988 to 1991, Wells was the restaurant critic for newsweekly L’Express and became the first American woman to hold such a position on a French-language publication. She’s won four James Beard Awards and has been recognized by the French government for her service to the country’s culture and cuisine.

But before Wells was embraced as an ambassador of France’s culinary scene, its old guard bristled at the prospect of their new American colleague.

“The French critics hated me!” she says. “They wouldn’t believe that not just a woman, but an American woman, was going to supersede them or compete with them.”

Fortunately, Wells could only laugh.

“I remember one of the famous French chefs who was on TV said, ‘Oh, that woman, she’s just a hamburger lady from America.’ ”

None of this deterred Wells, who endured sexist sommeliers and research excursions during which she and her assistant were the sole women eating lunch in restaurants clouded with cigar smoke. As in her cooking, she remained diligent and meticulous in her research.

“I remember one of the famous French chefs who was on TV said, ‘Oh, that woman, she’s just a hamburger lady from America.’ ”

“I would go three times to a restaurant,” she says. “One time with a female friend at lunch; one time with my husband on a weeknight; and one night on a weekend with another couple.” After the third visit, she would introduce herself (having made the reservation under another name) and ask to spend a day in the kitchen.

“Spending a day in the kitchen would teach you a whole lot about the restaurant,” she says. “That was such a luxury.”

It was through these kitchen visits that Wells forged many of her relationships with France’s esteemed chefs, including Robuchon. Observing the preparation and execution of a recipe and re-creating it in her home kitchen was also an invaluable culinary education that, true to her Midwestern generosity, she couldn’t help but share.

In 1995, Wells, along with Walter, opened At Home with Patricia Wells, an intimate cooking school hosted in their 18th-century farmhouse, Chanteduc, in Provence. Wells led small groups in weeklong classes designed to impart kitchen skills and techniques, and to deepen participants’ appreciation and understanding of French cuisine. Later, they opened a second school out of their Paris atelier.

In January, nearly 30 years after the first At Home with Patricia Wells cohort convened at Chanteduc, Wells taught her final class — Black Truffle Cooking Extravaganza, her favorite — officially closing the book on her culinary career.

Always in Season

“I was listening to a friend who’s a singer the other day. And I had thought earlier in the day: I don’t cook the things I used to cook 30 years ago,” Wells says. “And I was wondering, do you still sing the songs you sang 30 years ago?”

While Wells’s skill set may not suffer the strains of age like a vocalist’s pipes, her cooking has nonetheless shed its former extravagance in favor of something better suited to her present lifestyle.

“If I taught the recipes I’m making today, they’d say, ‘Why’d I pay for this cooking class? I’m only learning to steam or I’m only learning to sear!’ ”

But Wells isn’t teaching cooking classes anymore. She doesn’t have any more books coming off the press, and she won’t be reviewing a restaurant any time soon.

“I’m not sure I could be a restaurant critic for the modern cuisine of France right now,” she says. “Those chefs have a totally different palate than mine.”

Instead, her tastes have returned to the ones she knew before France, and the ones that have always endeared her to her adopted country. In a serendipitous antecedent to her later classification of Robuchon’s cuisine, Wells wrote in a 1979 New York Times column titled “Fish Boil: Culinary Tradition in Bunyan Country” that Midwestern meals are measured, in part, on the “unpretentious use of what is fresh and at hand.”

Today, she and Walter sear sea bass in oil, butter, salt, and pepper in their home kitchen and serve it with salad and wine. Dessert, no longer the show-stopping pastries of her heyday, is a homemade sorbet. Meals are prepared with ingredients from the timeless mainstay that has enchanted Wells in every season of the year since she first came to France: the local market.

“Thank God France still does everything in terms of season.”

“We were out this afternoon having lunch in France, in Le Marais, and we were passing markets, and I just thought, ‘Thank God France still does everything in terms of season,’ ” she says. “People get excited about the opening of something, and it’s great that there’s a seasonality with everything.”

People includes Wells, who enthusiastically rattles off the bounty that featured in market stalls during their visit: walnuts, grapes, figs, sea scallops, and Vacherin Mont d’Or (a cheese only available from September through March). She laments the merchants who disappeared after markets were disrupted during the pandemic — including the peppercorn vendor who dubbed her “Madame Timut” after her preferred variety — and commends young people for taking up traditional trades like farming and cheesemaking.

“Sometimes I go to the market even when I don’t need anything,” she says. “Sometimes I go to the market and spend five euro just for the experience.”

Apart from the author herself, perhaps her beloved markets are most emblematic of Wells actuelle: gregarious, generous, good-natured, humble, homegrown, and at once both seasonal and timeless. •

Megan Provost ’20 is a staff writer for On Wisconsin

Published in the Spring 2025 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.